|

On the road to Kargil,

Dras

A salute to the spirit of infantrymen

By Amarinder

Singh

WHILE we continue to be glued to

our television sets as military spokesmen brief us on

day-to-day operations in Dras and Kargil, and while

newspapers are filled with pictures of soldiers in body

bags, and funerals taking place with full military

honours, our thoughts go out to the bereaved families of

our officers and men who died serving the nation.

An epitaph by A.E.

Housman comes to mind:

Here dead we lie, because we did not

choose to live and shame the land from which we sprung.

Life, to be sure, is nothing much to lose; But young men

think it is and we were young. Here dead we lie, because we did not

choose to live and shame the land from which we sprung.

Life, to be sure, is nothing much to lose; But young men

think it is and we were young.

While tales of courage

abound and officers and men continue to volunteer to

serve their country in the ongoing operations, what

perhaps fails to hit home to the average reader or viewer

is the inhospitable and desolate part of the country in

which our soldiers are operating and the extreme hardship

that they have to put up with.For those who have not seen

or had any experience of this terrain, it is a difficult

task to understand it.

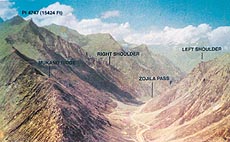

The road fromSrinagar to

the Indus valley and Leh, the capital of Ladakh, passes

over the dominating Zoji La Pass at 11,432 feet.Starting

fromSrinagar, the road winds its way up the Sind valley

to Sonamarg, 52 miles to the north.From Sonamarg, a road

goes east to a village called Baltal, which stands on a

road junction.From here a road goes east up to the Zoji

La Pass and another to the south leads to the holy

Amarnath cave and further to the tourist resorts of Shesh

Nag and Pahalgam.

After crossing Zoji La,

situated on the rugged and virtually impassable Pangi

range, the road continues for 2 miles through an open

valley, at the same altitude,with craggy mountains as

high as 6,000 feet above the floor of the valley on

either side. The road then reaches an open plain called

Gumri which stands at the head of the Gumri Basin and at

the far end of which is Machoi.

From Machoi, the road

descends 8 miles to a large pasture called Minamarg at

the far end of which lies the first village east of the

Pass,Matyan. Five miles beyond Matyan is Pindras and

another 8 miles on is Dras, standing at 10,609 feet.This

is the coldest place in India. In winter, temperatures

occasionally fall as low as minus 50°C. There is no

vegetation of any type other than small alpine scrub and

bushes which can be seen occasionally as one drives

along.

From

Matyan, a track leads to the north-east to the Mashkoh nullah

which finally ends up at Dras. FromDras, the road

continues to Kargil, then down to the Indus river. From

Matyan, a track leads to the north-east to the Mashkoh nullah

which finally ends up at Dras. FromDras, the road

continues to Kargil, then down to the Indus river.

The Pangi range, running

north-west and south-east of the Zoji La Pass, is

virtually an impenetrable barrier. Starting on the south

bank of the Indus river close to Gilgit, the first

prominent and dominating height is the massive mountain,

Nanga Parbat. Between the Nanga Parbat and the Zoji La

Pass, this impassable range permits just one crossing,

the Burzil Pass, which connects Gilgit to Gurais and then

down to the Kashmir valley. It is the area that was

captured in a gallant action by a two battalion group in

1948-- I Grenadiers and the 2/4 Gurkhas.

To the east of the Pangi

range lies the great Deosai plain in Baltistan.A plain

only in name as it is somewhat lower, but sharp craggy

mountains rise from it in steep jagged-edged ranges. Dras

and Kargil are situated on the south-eastern edge of this

plain, along the Srinagar-Leh road. The Deosai plain then

ends in the east, on the west bank of the Indus river.

To the east of the Indus

lies the Ladakh range and to the north of this the

Karakoram range on which is situated the famous Siachin

and Baltoro glaciers. Further north is the well-known

mountain, Mount K 2.

The only approach

fromPakistan into these rugged mountains dominating the

Srinagar-Leh highway is from Pakistan to Gilgit and then

along the Indus valley to Skardu. From here and from

Parkutta, Marol and other such small towns along the

Indus, all familiar names from the Kashmir operations of

1947/48, tracks penetrate the mountain ranges on the

Deosai plain and these too are few and far between.

Those of us in our service days who have

had an opportunity of serving in these or similar areas,

are well aware of the impossibility of this type of

terrain. Patrols which we went on to reconoitre routes in

unchartered country ended up in nine cases out of ten

being abandoned, as one came up against sheer rock faces,

impassable even to trained mountain troops. Those of us in our service days who have

had an opportunity of serving in these or similar areas,

are well aware of the impossibility of this type of

terrain. Patrols which we went on to reconoitre routes in

unchartered country ended up in nine cases out of ten

being abandoned, as one came up against sheer rock faces,

impassable even to trained mountain troops.

Defensive positions

established on those mountain tops, which could be

reached by these few available tracks, had to rely

entirely on mules, and in some cases on human porterage,

when certain inclines mules too could not negotiate. All

this for the bare essentials of existence such as water

and food, not to mention heavy weapons and ammunition.

Sending unacclimatised troops to these heights led to its

own problem of mountain sickness (pulmonary oedema). Once

a soldier succumbs to this curse, he has to be

immediately evacuated to a lower altitude for treatment.

Death can also result in a matter of hours.

In May 1965, Pakistan

attempted one of its periodic forays into Indian

territory, the Rann of Kutch. The Indian Army responded

with operation Ablaze to push them out, which we

successfully did.While Kutch was the focus, the Army

Commander, Western Command, Lt Gen Harbaksh Singh, to

whom I was ADC, decided to tidy up our line and push the

enemy off two posts overlooking Kargil, Pt 13620 and

‘Black Rocks’. The 121 BrigadeGroup at Kargil

responded, and 4Rajput and 1 Guards captured both these

positions after bitter fighting and after taking heavy

casualties.I was in Kargil then and asked for permission

visit to a friend, then with1 Guards, Lt R.P. Singh

(since retired as a Major-General) up at ‘Black

Rocks’. I had recently left 4 Mountain Division

after having served for two years between 12,000 and

16,000 feet and I remember how steep and impossible that

climb was.

Today

we see press reports of ‘pincer’ movements and

other military jargon being bandied about by

well-intentioned, though militarily ill-informed,

journalists.Quick-moving armour battles may have

‘pincer’ or other movements but not where each

mountain has to be tackled separately. The old maxim

known to infantrymen since the grim and bloody battles of

the North West Frontier in the twenties and thirties is

that ‘those who hold the heights have already won

half the battle’ is the order of the day. Why we

lost these heights in the first place is another story

and some day we shall hear of it. In the meantime, each

mountain must be fought for, or if possible, isolated by

cutting off the means of supply, called ‘line of

communication’ (LoC) in military parlance, thereby

starving them at the top. Today

we see press reports of ‘pincer’ movements and

other military jargon being bandied about by

well-intentioned, though militarily ill-informed,

journalists.Quick-moving armour battles may have

‘pincer’ or other movements but not where each

mountain has to be tackled separately. The old maxim

known to infantrymen since the grim and bloody battles of

the North West Frontier in the twenties and thirties is

that ‘those who hold the heights have already won

half the battle’ is the order of the day. Why we

lost these heights in the first place is another story

and some day we shall hear of it. In the meantime, each

mountain must be fought for, or if possible, isolated by

cutting off the means of supply, called ‘line of

communication’ (LoC) in military parlance, thereby

starving them at the top.

Each mountain is perhaps

held by a section (10 men) or a platoon (40 men) and that

in itself is a formidable opposition. In virtually all

cases, one cannot deploy more than few men, perhaps a

section, along a razor-sharp ridge. The final approach as

one reaches the top where the enemy defences are would in

some cases be even narrower. In such cases, even a single

well-placed medium machine gun would be enough to wreak

havoc on an attacking force. In 1965, during the famous

"Haji Pir’ operations, three battalion attacks

on successive nights by 4 Rajput, 19 Punjab and 7 Bihar

on the formidable ‘Bedori’ feature held by a

platoon of Pakistan’s 6 Azad Kashmir failed. Once

again, the final approach was along a razor-sharp ridge.

Infantrymen are perhaps the least

glorified soldiers of any operation of any army the world

over. In this age of speed and missile or laser

technology, air forces or swift armour operations appeal

more to an average civilian’s mind. In Kargil,

however, it is the infantrymen’s war and they

continue to fight relentlessly against heavy odds, the

elements, a well-entrenched enemy shooting down at him

while he struggles up the steep and rugged mountains

carrying loads of sixty to seventy pounds. Once wounded,

evacuation is an impossibility while the operation is on,

and many die quietly without urgent medical attention

being made available. Infantrymen are perhaps the least

glorified soldiers of any operation of any army the world

over. In this age of speed and missile or laser

technology, air forces or swift armour operations appeal

more to an average civilian’s mind. In Kargil,

however, it is the infantrymen’s war and they

continue to fight relentlessly against heavy odds, the

elements, a well-entrenched enemy shooting down at him

while he struggles up the steep and rugged mountains

carrying loads of sixty to seventy pounds. Once wounded,

evacuation is an impossibility while the operation is on,

and many die quietly without urgent medical attention

being made available.

General Francisco

Franco, the Spanish dictator in 1922, once described an

infantry soldier as follows: ‘Infantry men are they

who, in the frosts and storms of night, watch over the

sleep of camps, climb under fire the highest crests,

fight and die, without their voluntary sacrifice

receiving the reward of heroism’. How relevant it is

to Kargil 77 years later.

Today, there is a

general wave of support sweeping the country for our

defence forces, particularly the Army, in its most

difficult task. I have, however, witnessed such support

and sympathy in the wars of 1962, 1965 and 1971, but

sadly once operations are over, the soldier is forgotten.

There could be no finer tribute to his sacrifice than for

us to help the families of those who have fallen, not

only in the short term but to implement long-term

measures as well by providing education and later jobs to

their children. If each industry would adopt a couple of

families for this purpose, our dead would rest in peace.

We, that are left behind, owe it to them. If we do so, we

can feel satisfied that we have done our duty to the best

of our ability.

Laurence Binyon’s

immortal epitaph on the memorial to the unknown soldier

of the Great War of 1914/18, at London, aptly sums up the

national feeling today. The young officers, JCOs and men

of our army, who have laid down their lives and will

continue to do so till our territory is cleared of all

intrusion, must never be forgotten.

They shall not grow

old.

As we that are left grow old;

Age shall not weary them,

Nor the years condemn.

At the going down of the sun

and in the morning

We will remember them.

|