|

Mistresses of

Crossover

Cinema

These three

Punjabi women have done cinema proud. They have taken Bollywood

to the world and brought the West to Bollywood. Their films,

exploring human mindscape and relationships in a variety of

socio-cultural settings, are a hit with both western and Indian

audiences.

Randeep Wadehra

reels off the acclaimed contribution of film-makers Mira Nair,

Gurinder Chadha and Deepa Mehta to cross-cultural cinema

THESE

three women have managed to straddle the cultural twain:

Amritsar-born Deepa Mehta, Bhubaneshwar-born Mira Nair and

Nairobi-born Gurinder Chadha are highly talented film directors,

producers, writers and actors. What sets these three apart from

their peers is the fact that they are Punjabi women who have

successfully spanned the East-West civilisational fault – as

far as cinematic sensibility and creativity are concerned. Their

works are watched, understood and critically acclaimed as much

in India as in the West.

One can have some

idea of their calibre if one takes a look at the awards they

have won. Mira Nair’s works, apart from nominations to BAFTA

and Oscars, have won Golden Camera (1998), Silver Ribbon (1992),

New Generation and Lilian Gish Awards (1998), as well as Golden

Lion (2001). Deepa Mehta bagged the 2006 Genie Award for

outstanding achievement in cinematography, Golden Kinnaree Award

at Bangkok International Film Festival (2006), The Silver Mirror

(2006) etc, along with the recent nomination to the Academy

Awards for Water. In addition to being nominated for

Writers Guild of America’s best original screenplay award in

2003 (Bend it like Beckham), Gurinder Chadha’s

contribution to cinema was recognised with the OBE decoration by

the British government in June 2006.

|

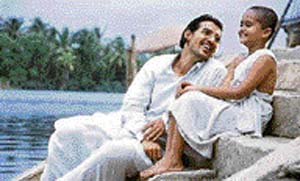

FILMS WITH A MESSAGE: Stills from Deepa Mehta’s Water (top) and Gurinder Chadha’s Bend it like Beckham (above)

|

The trio is

equally comfortable while making movies, telefilms and

documentaries for Indian as well as western audiences. Nair has

made flicks like Salaam Bombay, Mississippi Masala, The Perez

Family, My Own Country, Hysterical Blindness, Kama Sutra,

Monsoon Wedding, Vanity Fair and The Namesake to name

a few. Mehta’s better known movies include At 99: A

Portrait of Louise Tandy Murch, Sam & Me, Camilla, The

Republic of Love, Bollywood Hollywood, Earth, Fire and Water.

Some of the better known productions from Gurinder Chadha’s

oeuvre comprise The Mistress of Spices, Bride and Prejudice,

Bend it like Beckham, What’s Cooking?, A Nice Arrangement,

What Do You Call An Indian Woman Who’s Funny?, Bhaji on

the Beach and Acting Our Age.

The three

film-makers have explored human mindscapes and

relationships in a variety of socio-cultural environments, which

are generally alien or oppressive or both. You get a rather

detailed look into the world of the marginalised or the outsider

in movies like Salaam Bombay (street children), Earth

(Lenny, the Parsi girl) and Water (the exploited widows).

You get a glimpse of inter-racial relationships in movies like The

Mistress of Spices, The Namesake and Mississippi Masala.

Quite a few of the movies are about adaptation and adjustent to

alien cultures or individuals from different backgrounds.

In Bend it like

Beckham, Jasminder Bhamra feels more British than Indian and

wants to play football like her peers such as Juliette. But her

mother forbids her. In the ensuing struggle between the

subcontinental orthodox mindset and western liberal values, the

latter win as her parents give in to her wishes. Simiarly, in The

Namesake you find Ashok and Ashima – married according to

Bengali traditions – trying to adjust to their children’s

lifestyle, especially son Gogol’s American way of living. In

turn Gogol too has to come to terms with the relative frailty of

love relationships in the western milieu — be it his affair

with the American Maxine or marriage with the Indian Moushumi.

But, the movies

are not just about families caught in the vortex of cultural

differences. There are individuals outside families too who

adapt to ‘the other’ in order to minimise the effect of

cultural clash. For example Sam & Me focuses on the

equation between a Muslim boy and an elderly Jew living in

Canada.

Another striking

feature of the trio’s works is predominance of female

protagonists and their strong characterisations. Whether it is

the neglected Sita and the abandoned Radha coming together in

quest of love (Fire), the domineering Madhumati, the

innocent imp Chuiya, the yearning-for-freedom Kalyani (Water)

or Tilo, who is torn between her love for Doug and the call of

the spices, all these characters leave more than a lingering

impression on one’s mind. Moreover, humour, mischief and joy

do make an appearance in most of their movies.

However, there are

differences in the manner in which the three film-makers treat

their subjects. Chadha uses lots of colour that exudes energy.

If you remember the rather vigorous dance sequence in the bazaar

in Bride and Prejudice you will recall the frisson it

triggered off in your entire being. Even in The Mistress of

Spices or Bend it like Beckham you hardly find any

gloomy ambience although colours are relatively muted in the

former.

You can say the

same about Nair. She, too, prefers bright ambience for her

movies. This is not to say that the two are unmindful of the

narrative’s tenor or that they lend artificial hues to the

general mood and texture. The end product of their efforts is

eminently authentic. Mehta, in contrast, has not hesitated while

employing sombre colour and complexion — you notice this

especially in the ‘elements trilogy’ Earth, Fire and Water.

Then there is the matter of cinematic metaphor — rains, for

example.

Ever since its

inception, the Indian cinema has been using rains to portray

sensuality, joy, celebration and rejuvenation. However, in Monsoon

Wedding Nair uses this device to depict something more than

joy and celebration. Rain also becomes the symbol of the coming

together of different classes, as the well-off mingle with their

minions in a communal rain-drenched dance. More importantly, it

is a happy aftermath to Shefali Shah’s angst-ridden outburst

against her paedophile ‘Tej Uncle’.

In Water,

on the other hand, rains bring in transitory, nay illusionary,

joy in the lives of Kalyani and Chuiya. When the two dance in

the room as it drizzles outside, you are filled with sympathy

for them, for you instinctively know that their fate has already

been sealed by society. Here, the rainfall is more a symbol of

hope-amidst-hopelessness than an expression of sensuality.

Mehta also employs

light and shade to effectively communicate with the viewers. For

example, in the climactic scene in Water Shakuntala

places Chuiya into Narayan’s hands as the train moves from the

rather dark platform towards the sunlit world beyond. You

realise that at least the widowed child has escaped further

molestation at the hands of upper-caste landlords for whom

widows are nothing more than sex objects.

Come to think of

it, things haven’t changed much since 1938 if one takes a look

at the plight of abandoned widows in Varanasi and Vrindavan —

the legend at the end of the movie is a stark reminder of this

enduring blot on our society. Contrast this with the movie’s

beginning — Chuiya travelling with her husband and in-laws

amidst verdant greenery. The grey colours suddenly obliterate

all brightness when she becomes a widow. Dark shadows play on

her expressionless face as her locks are shorn off.

While watching

their movies, you tend to forget the language in which these are

made – Hindi, English or Hinglish, and ignore the nationality,

ethnicity or cultural identity of the characters. The imagery is

so powerful and lucid that you tend to get involved with the

flow of the narrative. Truly, Mehta, Nair and Chadha are the MNC

of transcultural cinema.

|