|

Rabindranath

Tagore’s 150th birth anniversary falls on May 9

Tagore tales on

talkies

The works of Rabindranath

Tagore have always fascinated filmmakers, as these are universal

— in time, space, emotions and human relationships, writes Shoma

A. Chatterji

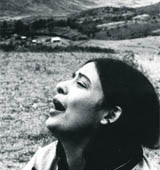

Credit for the most brilliant cinematic, hard-hitting and metaphorical use of Tagore’s songs goes to Ritwik Ghatak in Meghe Dhaka Tara |

Rabindranath

Tagore’s writings bring up images of lyricism and romance.

Many filmmakers feel that the horizon of a Tagore creation —

be it poetry, fiction, essay or drama — is too large,

all-encompassing, complex and alien to Indian masses,

conditioned to ‘popular’ literary figures like Sarat Chandra

Chattopadhyay and Bankim Chandra Chattopadhyay. Their creations,

it is felt, are more cinema-friendly. The 14 remakes of Devdas

in different Indian languages is an example.

The homespun

philosophy of Sarat Chandra and the romantic spirit of Bankim

Chandra had more appeal than the non-conformist and feminist

themes, which Tagore dealt with. Yet, Tagore has been recognised

as a rich literary source for very good cinema. Satyajit Ray’s

films based on Tagore’s works offer the best example. In 1961,

Ray made Teen Kanya (Three Daughters), on three Tagore

short stories — Postmaster, Monihara and Samapti.

The other Tagore works he filmed are Charulata and Ghare

Baire.

Tagore’s

works are universal — in time, space, emotions and human

relationships. They offer filmmakers a challenge to make the

film as powerful, credible and appealing on celluloid as it is

in print. A film based on, adapted from, interpreted from Tagore’s

oeuvre offers scope for argument, discussion, analysis, debate

and questions among the audience, critics and scholars. A

massive volume of scholarly treatises came out after Satyajit

Ray’s Charulata, leading to a new genre — writing on

films based on Tagore’s works.

Charulata

(1964) is based

on Nastaneer (The Broken Nest, 1901). Charulata,

the film, and Nastaneer, the story, is set in 1879, when

the renaissance in Bengal was at its peak. Western thoughts of

freedom and individuality were about to ruffle the calm feathers

of a feudal society. Women’s liberation was being talked

about, but not beyond few cases of widow-remarriage and some

education. Intelligent, sensitive, graceful and serene, Charu

was a traditional woman, whose mindset slowly and steadily

absorbed waves from the world beyond.

Charulata is the most critically discussed among Tagore’s works

adapted by Satyajit Ray |

Charulata

is the most hotly debated, variedly interpreted, widely

discussed and critically questioned among Satyajit Ray’s

films. Most of these debates are around Ray’s fidelity to the

Tagore original. Tagore and his works are too sacrosanct for

a filmmaker to interpret otherwise was the general feeling. Ray

responded to attacks on his alleged distortion of the original

through his article Charulata Prasange in the collection

of articles, (Bengali) Bishay Chalachitra.

In Chokher

Bali, Rituparno Ghosh adapts the many worlds of Tagore so

that it reflects our past filtered into our present. Ghosh

concentrated on sound design to bring about the message of the

political uprising in Bengal, happening at the same time, as the

disruption of Mahendra’s marriage inside the home.

The rising

crescendo of "Vande Mataram" filtering into the

home, the sound of the horse carriage moving away to suggest

Mahendra taking Binodini to the doctor, a thumri floating

across the River Ganga in Benaras, the chanting of holy Sanskrit

mantras to ease the death of an old widow on the banks, offer a

fourth dimension to the narrative and cinematographic space at

the same time. These worlds play around with intertextuality,

elements of the post-modern in cinema. Yet, they do not take

away from Ghosh, the originality and the uniqueness of his

individual style.

Another

filmmaker Tapan Sinha remained fiercely loyal in his rendering

of Tagore’s works into cinema. Yet, he did introduce his

directorial signature in these films. In Kabuliwalla, he

introduced an imaginative, pre-titles prologue. For around 10

minutes, a panoramic view of the arid, rough, hilly terrain of

the Afghanistan landscape comes up, with a slowly moving line of

camels in silhouette — the only sign of life. The soundtrack

is alive with the earthy music of Afghanistan.

This

establishes the time-place-culture setting of Rahmat, the

Kabuliwalla, throwing up subtle and strong images of his

relationship with his daughter, Rabeya. As the camera shifts

from the dry terrain and the camels in silhouette to the railway

tracks, suggesting Rahmat’s journey to Calcutta, the titles

begin to come up.

Tapan Sinha

made four films based on Tagore’s works. These are Kabuliwalla,

Khsudita Pashan, Atithi and Kadambini. In Khsudita

Pashan, he used dreams and fantasy to heighten the intrigue

of the romance not there in Tagore’s story. In other films, he

used Tagore’s songs generously and to good effect. In Daughters

of the Century, Sinha chose Tagore’s Living or Dead

(1904).

Kadambini, a

young widow, is taken to be dead. Before she is cremated, a

storm stops the rituals and people run away leaving the ‘corpse’.

When she comes home, the family disowns her, taking her to be

her own ghost. Unable to make them believe that she is alive,

she drowns herself in the family pond, creating one of the best

last lines of Bengali literature — "Kadambini died to

prove she did not die."

In Chaturanga

(2008), Suman Mukhopadhyay remains loyal to the original

story. The cinematic innovations are dictated by change in the

medium from word to celluloid, enriching, rather than distorting

the film as it moves from one philosophical idea to the next,

expressed through the wild wanderings of Sachish, the eternal

questioner, who finds no truth in the greys that lie between the

black and the white of life. The novel is divided into four

chapters named after the four main characters — Jathamoshai,

Sachish, Damini and Sribilash.

Tagore’s

novel is a first person, point-of-view narration of Sribilash,

who is more an observer and a commentator than a character.

Mukhopadhyay cut out the voice-over to convert Sribilash into a

major character. The opening frame shows Sachish sitting on a

beach, his back to the camera, while a group of white-robed Sufi

singers wander across the landscape.

The closing

frame shows a confused Sachish, watching the Sufi singers

perform their devotional song, the burnt embers of the fire they

had made lying on one side of the beach. The narrative returns

to the beach again and again, like a metaphor on the continuity

of life — and death.

Filmmakers have

generously drawn upon Tagore’s music, songs, poetry in Bengal.

Hindi cinema has had few interpretations and cinematic

adaptations of Tagore. Examples are Kabuliwalla produced

by Bimal Roy and Char Adhyay by Kumar Shahani.

Bimal Roy’s Sujata

used scene from Tagore’s dance-drama based on a legendary

Buddhist tale Chandalika to draw parallels with the story

of an untouchable girl. Sujata used the original tune of

a Tagore song for another song, picturised on Sunil Dutt.

Musical adaptations from Tagore were prolific in the 1950s and

1960s in Hindi films. Composers like S.D. Burman, R.D. Burman

and Hemanta Mukhopadhyay were strongly inspired by Tagore’s

songs and often used his original music in their compositions.

In Bicharak,

based on a Tarasankar Bandopadhyay novel, Tapan Sinha used a

Tagore song as a leitmotif to express the feelings of guilt that

keep haunting the hero, a judge, since the death of his wife in

a fire. Credit for the most brilliant cinematic, hard-hitting

and metaphorical use of Tagore’s songs goes to Ritwik Ghatak

in Meghe Dhaka Tara and Komal Gandhar. He

turned the romance and lyricism, linked to Tagore’s musical

compositions, on its head and changed it to fit into the dark,

exploitative and oppressive ambience of Nita’s life — and

death — in Meghe Dhaka Tara, complementing the songs

with powerful visual frames and a brilliant sound design.

Lines from a

Tagore poem inspired Rituparno Ghosh’s Asookh. Ghosh

also used Tagore’s songs and poetry in Utsab. He

inserted a dramatised scene from Chokher Bali, the novel,

into the screenplay of Bariwalli.

Tarun Majumdar’s

fine sensibilities come across through Tagore’s songs in his

films. In Nimantran, Majumdar used Tagore’s poem,

"Nirjharer Swapno Bhango", recited without

vocal inflections by the hero. In Balika Bodhu, the

resident tutor, an old man, keeps to himself and plays a

patriotic Tagore song on his violin. Later, when the

police comes to arrest him, we discover that he was a terrorist.

The significance of the song then comes across.

Some of the

films made on Tagore’s works are — Naukadubi, Shubha O

Debotar Grash, Steer Patra, Chhuti, Malancha, Malyadaaan,

Jogajog, Chirokumar Sabha, Chhelebela, Bouthakuranir Haat, and

Nishithe. Purnendu Patrea’s Streer Patra played

around with animation in the graphic titles, still photographs

in the closing shots. But he stuck to the original story. The

result was confusing. Chhuti defined a moving, subtle

treatment of a tragic love story directed by Arundhati Devi.

Functioning in

an ambience of illiteracy and a diversity of languages, Indian

cinema has evolved into a major medium of communication to bring

Tagore to the masses. The process works backwards where

sub-titled films adapted from a Tagore original could inspire

viewers to read the literary original after having watched the

film. When an Indian publishing house brought out an English

translation of Chokher Bali almost simultaneously with

the release of the film, the book was a sell-out. Though the

film failed to repeat the magic.

Tagore’s

films as a genre effectively blend words with visuals yet

sustain the independence of the original literary work, as well

as the independence of the film that has an identity of its own.

When a director chooses Tagore, he offers an alternative

world-view that is his interpretation of a Tagore creation. In Nastaneer,

in the original story, Bhupati departs in the end, leaving Charu

to her grief and bewilderment. Ray brings them together in Charulata

to live forever in a state of suspended animation. Ray’s story

is as daring today as Tagore’s was when it was first written.

Yet, there is no element of shock, for the process of life comes

out silently.

|

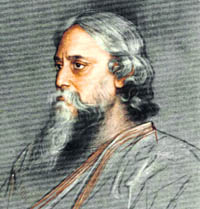

Creative

genius

In

stature, stride and sweep, Rabindranath Tagore (1861-1941)

is an all-round creative genius the likes of which have

seldom been seen, if at all, in any country. The Tagore’s

roots were affluent, distinguished, in many ways

exclusive, if not alienated. His grandfather, Dwarkanath,

who built the family fortune, was known as

"Prince" and counted among friends, people as

far removed as Raja Rammohan Roy and Queen Victoria. His

father, ‘Maharshi’ (The great sage) Devendranath, was

a man inclined to spiritualism. He broke away from

orthodox Hindu ways and joined the Brahmo Samaj.

Rabindranath, the 14th and his last child, was born on May

7, 1861, in the ancestral mansion of the Tagore’s at

Jorasanko in central Calcutta. In

stature, stride and sweep, Rabindranath Tagore (1861-1941)

is an all-round creative genius the likes of which have

seldom been seen, if at all, in any country. The Tagore’s

roots were affluent, distinguished, in many ways

exclusive, if not alienated. His grandfather, Dwarkanath,

who built the family fortune, was known as

"Prince" and counted among friends, people as

far removed as Raja Rammohan Roy and Queen Victoria. His

father, ‘Maharshi’ (The great sage) Devendranath, was

a man inclined to spiritualism. He broke away from

orthodox Hindu ways and joined the Brahmo Samaj.

Rabindranath, the 14th and his last child, was born on May

7, 1861, in the ancestral mansion of the Tagore’s at

Jorasanko in central Calcutta.

"Chokher

Bali is timeless"

"It

was the delicate interplay of relationships that touched

me. The story offered a vast matrix of relationships,

which, I, as director, could play around with in a myriad

different ways. Chokher Bali struck me as a very

original text to begin with. It deals with unfaithfulness

in the man-woman relationship within the institution of

marriage. Maybe, if you pick on this lack of faith, you

may find that one common link between Chokher Bali

and Bariwali. The ‘period’ flavour, I could

invest the film with, was another attraction. Tagore’s

original story did not have any time-reference. The

characters seem to be hanging in limbo. The film offered

me the chance of preparing the ‘period’ for the film.

In Shatranj Ke Khilari, Ray created the historical

context for the film turning the ‘period’ into a ‘character.’

He did the same for Ghare Baire and Charulata.

I have done the same in this film" "It

was the delicate interplay of relationships that touched

me. The story offered a vast matrix of relationships,

which, I, as director, could play around with in a myriad

different ways. Chokher Bali struck me as a very

original text to begin with. It deals with unfaithfulness

in the man-woman relationship within the institution of

marriage. Maybe, if you pick on this lack of faith, you

may find that one common link between Chokher Bali

and Bariwali. The ‘period’ flavour, I could

invest the film with, was another attraction. Tagore’s

original story did not have any time-reference. The

characters seem to be hanging in limbo. The film offered

me the chance of preparing the ‘period’ for the film.

In Shatranj Ke Khilari, Ray created the historical

context for the film turning the ‘period’ into a ‘character.’

He did the same for Ghare Baire and Charulata.

I have done the same in this film"

Direct

interaction

|

Rituparno Ghosh

|

Tagore’s Natir Pooja’s

dramatised version was first staged at the Jorsanko

Thakurbari in Kolkata in 1927. It was again staged at the

New Empire, Kolkata, on celebration of the poet’s 70th

birthday. An impressed B.N. Sircar, founder-proprietor of

New Theatres, invited Tagore to direct a film version

under the New Theatres banner. The New Theatres Studio

played host to Tagore in 1931. The studio was flooded with

crowds assembled to have a glimpse of the great poet.

Tagore directed the film, shot on NT Studio’s Floor

Number One. He also played a role and assembled his acting

cast from Santiniketan. Nitin Bose cinematographed the

film and Subodh Mitra edited it. The film was shot within

four days. Breaking the conventional rules of cinema, Natir

Pooja was filmed like a stage play. The story was

inspired by a tale from the Buddhist series in Abadan

Shatak. It was released at Chitra Talkies on March 14,

1932. Sadly, the prints of the film were reportedly

destroyed in a fire at the New Theatres. — SAC |

|