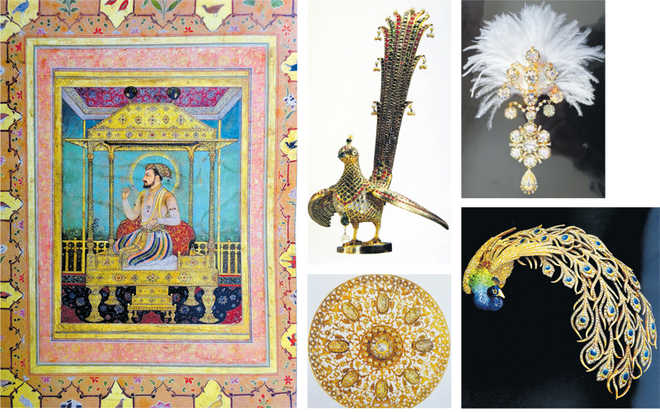

Clockwise: Shah Jahan on the Jewelled Throne. Opaque watercolour on paper. Mughal, ca. 1635; Huma bird from the canopy of Tipu Sultan. Gold inlaid with diamonds, rubies and emeralds. Mysore, 1787-1793; Turban aigrette. White gold set with diamonds. From the collection of the Maharaja of Nawanagar, 1935; Corsage brooch worn by Princess Anita Delgado of Kapurthala. Gold, diamonds and enamel. Ca. 1905; Hair ornament. Gold, pierced, engraved and set with diamonds. South India, ca. 1850

BN Goswamy

I know virtually nothing about jewellery. But, connected with it, two things —events one might call them — stand out in my mind to this day. In the course of one of my routine, but much-anticipated visits to the Sarabhai Foundation in Ahmedabad many years ago, Giraben Sarabhai — co-founder of the great Calico Museum of Textiles, and an exceptional, but self-denying researcher of things Indian in her own right — said she wanted me to see something she had been working on for some time. Past the Pichhwai collection in the foundation, and past the gallery of paintings, I followed her into another section of the magnificent mansion which houses these. There, inside a long horizontal showcase or vitrine, she pointed to a number of exquisite pieces of jewellery that belonged to her family and were now displayed here, spaced out but not heavily mounted: most delicately designed, fashioned, and crafted hair ornaments, and strings of necklaces, pendants on a string, a pair of ear-rings and a nose ring, bracelets and bangles, a jewelled belt, anklets and toe-rings: rubies and diamonds and emeralds and gold against a black background. I stood there, stunned by the quality of the objects. But then, suddenly, as I was looking, she asked someone to throw an electric switch, and everything changed. For far at the back of the showcase where one could not see it in the dark at first, was the nearly life-size blow up of an old painting of a comely princess artfully lying partially on her side on a couch, face turned towards us, with these very ornaments placed at precisely the same places on her body for which they were meant; it was as if she was wearing them: the hair-ornaments now adorned the hair, the ear-rings her ears. Strings of necklaces lazily hung around her neck and the bejewelled belt hugged her waist. It was sheer magic: the quality of the objects on display matched by the boldness and the imagination of the display. It was still ‘work in progress’, however, Giraben told me, for the jewellery gallery was a long way yet from completion.

The second occasion, or event, that I recall, was when I was asked — again a long time ago — to serve on a committee set up by the Government of India to inspect the jewellery belonging to the family of the Nizam of Hyderabad. The family had applied for permission to export and several determinations had to be made; I was asked to be on the committee, not because I was an expert in jewellery, but it was in the air then that I would soon be joining as the Director-General of the National Museum of India (something, incidentally, that did not happen, for I declined the honour). In any case, the committee was to meet in Mumbai where the jewellery lay stored in the vaults of a bank. There we headed, a small group of five persons, each one having only a vague idea of what we were going to see. But what we in fact saw took our breath away. For there we sat, in the dark vaults, looking at one drawer being pulled out after another, not for a few hours, but for something like a full two days. The sheer numbers were endless, and the quality nothing short of dazzling: emeralds the size of golf balls set to form turban-ornaments and waistbands and bazu-bands; strings of large moon-white Basra pearls serving as necklaces; rubies and sapphires and diamonds now glistening on nose-ornaments, now on finger-rings: the most exquisite stones cut and set by exquisitely skilled hands. It was almost too much to take in, for by the end of the sessions of seeing, our eyes — at least mine —were tiring, our minds reaching the point of exhaustion. What happened to the Nizam’s jewellery eventually and to our recommendations is a long and complex story that can be told another time, but here I am recalling only the blinding sights that we saw.

And then, more recently — last week in fact — I saw a show of the jewellery belonging to the Al-Thani family of the Sheikhs of Qatar on view at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London where I was lecturing. It was, once again, an experience of its own kind. I had heard about the Al-Thani jewellery show at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York last year, but had never ‘gotten there to see it’, as they say. Here, however, I was in London now, slowly pacing myself through the gallery led by Susan Stronge, senior curator at the museum, with quiet patience and intimate knowledge. She had been responsible for the show and has written a splendid catalogue for it. With her by our side, the show slowly revealed itself through stories, incidents, insights. It had been mounted with great flair by Celine Dalcher of the V&A, I need to add, drawing the viewer into that rarefied world of taste and opulence, bit by careful bit. As one walked into the gallery, one had the sensation of walking through a jewellery box in which everything shone with extraordinary brilliance against the unremitting black of the surroundings: walls, mounts, delicate pedestals inside vitrines, didactics, labels. The eye went directly to the object from the moment one approached the cuboid space which had been turned into cleverly paced intimate compartments. At the very mouth of this cave of lustre stood a riveting object: a turban aigrette formerly belonging to the royal family of Nawanagar in India: 17 luminous diamonds artfully set and topped by what looked like a weightless white plume. It was brilliantly lit and seemed to float in the air inside its plate-glass case. There were riches everywhere, for the Al-Thani family had been collecting objects that belonged for the most part to royal families — money being for it no object — and one saw exquisite objects; a corsage brooch in the form of a glittering peacock that princess Anita Delgado of Kapurthala once wore; the huma bird with a tremulous gem in its beak that once topped the royal throne of Tipu Sultan; the lustrous Timur ruby that had changed hands so many times and had once passed through Maharaja Ranjit Singh’s domain. And so on: more than a hundred objects. All this while, great paintings and photographs peered down the darkened walls of the gallery, placing objects in appropriate contexts. No chunky jewellery appeared here, no folk objects that are equally the glory of India. But, focussed as it was on riches, as one walked through the show, one learnt and absorbed. But one also wondered at the world that once was, at a past that has gone but somehow also manages to live on.