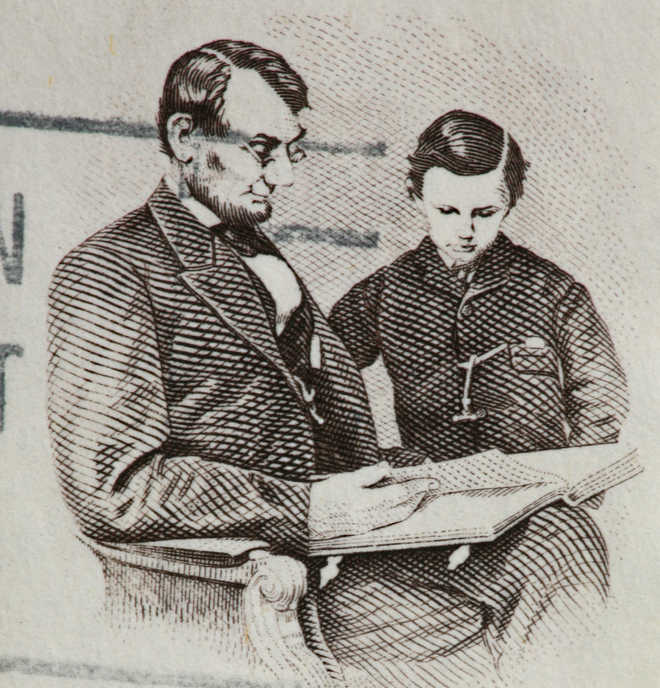

tragedy changeth a man: Lincoln’s loss of his 11-year-old son, Willie, who died of typhoid in 1862, left an indelible mark on him. In this 1864 photo, he is seen with his son Tad. iStock

Shelley Walia

George Saunders’s novel meets the demands of the Tibetan Buddhist concept of the “bardo”, the state of suspension between the personal and the historical, between the physical and the spiritual. A century and a half has passed, yet it seems intrusive, writes Saunders, to “dwell upon that horrible scene — the shock, the querulous disbelief, the savage cries of sorrow” at the death of a dear one. Abraham Lincoln’s loss of his 11-year-old son, Willie, who died of typhoid in 1862 is irreversible, leaving its indelible mark on him. “Well, Nicolay,” a wailing Lincoln remarked to one of his secretaries one afternoon, “my boy is gone — he is actually gone.”

Lincoln’s deep groans can be heard in that last hour that he and his family shut themselves in a room where the body lay, a child whose leading trait “seemed to be a fearless and kindly frankness, willing that everything should be as different as it pleased, but resting unmoved in his own conscious single-heartedness.” Lincoln’s pain is conspicuous: “His hair was wild, his face pale, with signs of recent tears, plainly evident. Lifting the child from the sick-box, the father sits on the floor gathering the body in his lap, “sinking his head into the place between chin and neck, sobbing unreservedly.” Saunders recalls in an interview how the idea of the novel came to him when “this image sprung to mind: a melding of the Lincoln Memorial and the Pietà.”

Lincoln would often remark that “Since Willie’s death I catch myself every day involuntarily talking with him, as if he were with me.” It is true that “Willie’s coffin was entombed for three years at Oak Hilland then shared the eighth car of Lincoln’s funeral train home to Springfield, where both father and son were laid to rest.” The novel gets a little mushy at places when a ghost-narrator thinks of the child as “a sweet little muffin of a fellow” or expresses ecstasy over “the feel of the tiny hand in yours — and then the little one is gone!” However, historically there is enough evidence that the loss of a son had a great impact on Lincoln’s world view pushing him more towards religion for comfort.

Using the form of multiple voices, a kind of a polyphony merges the historical with the fictional, the living with the dead, with the bereaved father moving from the physical world to the netherworld of Willie’s temporary afterlife. Using a deeply innovative form, Saunders manages to correlate the personal loss with the larger question of the bloody Civil War that Lincoln reconsiders through the sad demise of his son. It enables him to move from an inherent week temperament to a stubborn compassion for his countrymen through a paradoxical bringing of the war to an abrupt end by the use of large-scale violence once and for all. The “swiftest halt to the war might be the bloodiest.” Lincoln would like to “kill more efficiently.” This is the hard truth that gives the novel a moral undertone though bordering on the merciless. “Strange, isn’t it?” one character reflects. “To have dedicated one’s life to a certain venture, neglecting other aspects of one’s life, only to have that venture, in the end, amount to nothing at all, the products of one’s labors utterly forgotten?”

Excerpts from the written accounts of the war interlock with the imaginary voices of the lingering ghosts at the borderline of the living dead. Documented history juxtaposes with the imaginary to give us a stirring picture of the spirit of the dead son desiring to hang back in the body so as to be close to the wretched father who repeatedly visits him in the cemetery. Protracting your final exit from the body has the danger of turning into a monstrosity as seen in the ghosts of a printer named Hans Vollman or Roger Bevins III who go around with either an oversized member or a number of eyes and hands signifying unreciprocated life, disappointments and treachery. The voices of the dead fill up a medley that almost borders on a bleak and pathos-ridden world filled with lampooning through misspellings or word play that sardonically draw attention to class consciousness and social behavior in the Civil War era. Black ghosts enter into a brawl with the white plantation owner or merge into the spirit of Lincoln persuading him “to do something for us,” thereby bringing the question of slavery and emancipation to the forefront. Dexterously manipulating history and civil war to enter the mind and conscience of Lincoln and his times with traces of brutality, pathos and satire, the novel stands at once restlessly creative, dark and humorously human.