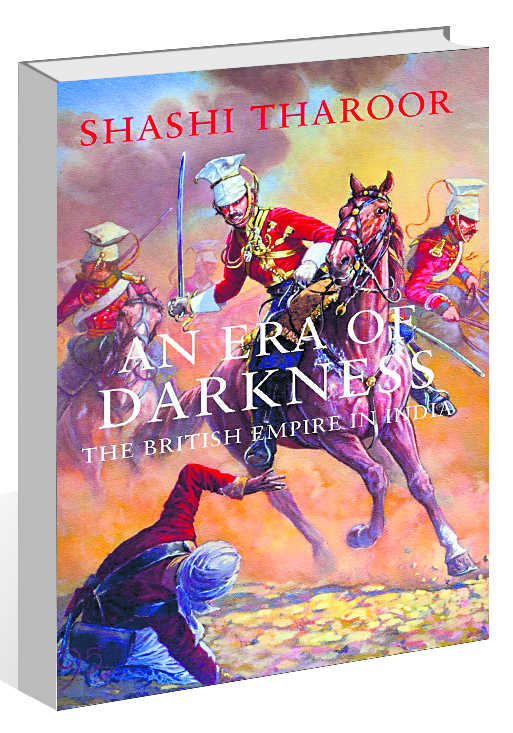

An Era of Darkness: The British Empire in India

Rumina Sethi

Shashi Tharoor’s book on the legacy of British rule in India reminds me of my days at Oxford, especially the occasions when I heard Nelson Mandela, Desmond Tutu and Salman Rushdie at the Oxford Union. The very air of the hall smelt of dissidence and radical thought intermingled with conservatism, as it must have done that evening when Tharoor stood up for India at the Oxford Union to speak on the motion ‘British owes reparation to her former colonies.’ No words were minced in the eight minutes’ account of the horror of colonialism so precisely and forcefully emphasised with a touch of humour as Tharoor repeated the oft-quoted statement that the sun does not set on the British Empire as God himself did not trust the British in the dark.

Following Shakespeare, who wrote in Macbeth that the ‘instruments of darkness tell us the truth,’ it may be surmised that the darkness that Tharoor underscores is clear from the examples he cites of half-a-million Indians dying in the British-induced Orissa famine of 1866, and in the torture and brutal killings following the 1857 Indian War of Independence, often referred to as the ‘mutiny’ by British historians.

India was indeed a land of plenty, writes Tharoor, boasting 27 per cent of the world’s economy, which fell to 3 per cent by the time the British had dealt with it. The land stood downsized, its trade wrecked and resources pillaged. The textile industry was destroyed completely by the callous amputation of the thumbs of the Bengal weavers. Interestingly, India’s tea export to Britain had reached £137 million by 1900. The proceeds from the plunder promoted Britain’s global economic status.

Though the genesis of the book goes back to the Oxford Union speech, it focuses primarily on India’s experience of the evils of empire and its impact on the people than on the question of reparation. More than any existing book on British history, Tharoor’s comprehensive account touches on various issues such as literature, cricket, tea, and the English language, apart from politics and judicial killings. And unequivocally from the Indian point of view, accentuating the horrifying legacy more than the benefits. The champions of the British Raj need to be told that the roads and the railways were built more for looting than for any assistance to the natives.

Shockingly, the ship-building trade in India was entirely devastated by the British when they banned Indian made ships from using the trade routes to India and China inspite of the better quality of wood used in the Indian shipyards. Yet British school children are fed on the ‘deliberate historical amnesia... that the Empire was some sort of benign blessing for the ignorant natives.’

The book galvanises a global public debate. It is timely enough to draw attention to an alternative view, a corrective to misconceptions that the British rule was not an exultant affair, as argued by historians like Niall Ferguson and Lawrence James. Though most people are aware of the basic fundamentals of this history, Tharoor makes a case for never forgetting the past.

But, for all its strengths, the book comes across more like an emotional plea. Even as Tharoor appears at great pains to attempt a historical argument, it is hard to shrug the uncomfortable feeling that he has curated an opportune text out of a trendy orgy of enthusiastic bluster against Britain that has become current, evinced in earlier discussions about the Kohinoor as part of British loot. Isn’t history all about might being right? India has enough history of invasions from Alexander the Great to Nadir Shah. The British were no different; why should they be expected to be more benign? And what of the Mughals? Surprisingly, Tharoor lets them off since they lived and spent their wealth in India.

I might also add that it was the British who became, to use Marx’s troubled expression, the ‘unconscious tool of history’ in ushering colonial modernity in India, although some would quibble that India already had its incipient forms of modernity. That apart, one could argue that the mammoth school of Indologists from Britain made available to the world some of our greatest ancient texts. If only Tharoor had been nudged from the Union towards the Oriental Institute Library, he would not have failed to notice shelf after shelf of books in classical Indian languages that had been translated by British scholars.

Notwithstanding, Tharoor’s book itself will work as an impetus for reparations by touching the conscience of the general public, enabling them to come to terms with one of the most contested periods of Indian history. A visit to the Jallianwala Bagh could trigger regret at least. Quantification of rape, loot and massacre is obviously not possible, but the world must realise that the Muslim League was born at the behest of the British to create a divide with the Hindus, and the emphasis on caste identities was a British strategy to counter the inclusive nature of Indian nationalism of the past.