Harish Khare

A defining event like the Emergency creates its particular solidarity, with its own sub-set of friendships, loyalties, prejudices and animosities and its own catechism of heresies and revelations. This book is a powerful, and at times moving, documentation of that experience.

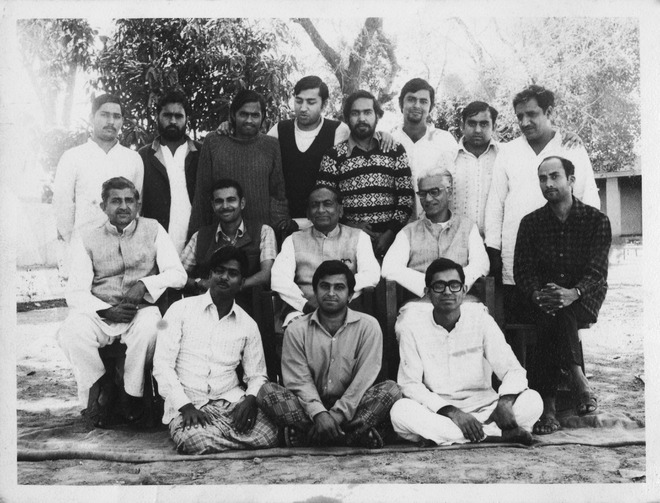

Coomi Kapoor dedicates the book to her husband, Virendra Kapoor, an intrepid soul who has remained un-reconciled to the Gandhis; Virendra found himself in jail along with Arun Jaitley, and that was the beginning of a life-long friendship; Jaitley has written the foreword; Coomi also happens to be sister-in-law to Subramanian Swamy, who was a very colourful dramatis personae in the Emergency drama.

Why Indira Gandhi imposed (and, later revoked) the Emergency remains a subject of conflicting narratives and revisionist interpretations.

The book attempts to refute the narrative that Indira Gandhi had no choice but to introduce the Emergency because of the disorder and anarchy sought to be unleashed by the JP-led opposition. Coomi Kapoor has produced a note by Siddhartha Shankar Ray, purportedly written six months before the Allahabad High Court's judgment against Indira Gandhi. In this note, Ray clearly outlines a blueprint for a quasi-authoritarian coup. Only research scholars would be able to shed light on the provenance of this note.

But this "breaking news" is not the strength of Coomi Kapoor's book. Its value lies in the author's detailed account of personal hardship, inconvenience and agony that the Emergency regime inflicted on her.

Two chapters, "A Strange New World" and "Black Diwali", chronicling how the "iron hand of the Emergency" touched her own family, are most disturbing.

Without giving in to bitterness, she conveys her sense of total despair: "Being a prisoner's wife with an infant, and having to keep a job at the same time, was tough. Ramnath Goenka, despite his sympathy for the JP movement, refused to pay Virendra's salary."

At one point, Virendra was suddenly transferred from Tihar to a jail in Bareilly: "I was stunned. I felt very helpless and alone. Bareilly seemed like the back of beyond." It is moving sentences like these that add up and give a composite picture of what a nightmarish experience the Emergency experiment turned out to be.

And, pray, why was Virendra put in jail? Because this “two-penny journalist had behaved rudely with” Ambika Soni, who was then playing a petty tyrant. That is it. Virendra was in jail for nine months, and Coomi talks of the psychological and mental toll that experience took on her husband.

And, then, there was the Swamy business. "Despite Virendra's release from prison, the shadow over our lives did not lift. In fact, the nightmare for our family was to continue, with the Emergency regime harassing my parents, and launching a countrywide hunt for my sister Roxna's husband, Subramanian Swamy."

A similar fate must have been visited upon hundreds and hundreds of Indian citizens. "An ugly feature of arrests and detentions under Defence of India Rules (DIR) was the immediate re-arrest of persons released on bail."

Moving and painful as these details are of the treatment meted out to Virendra and the rest of her family, she manages to convey a larger picture of an authoritarian regime and its appetite for vendetta, harassment and intimidation against the hapless citizen. An unaccountable regime allows petty officials to settle personal scores. "Indeed at the local level, Congressmen used the Emergency to settle personal scores with their neighbours, and business and professional rivals," writes Coomi.

Emergency was our first brush with authoritarianism. Coomi does well to sketch out such a regime's capacity to generate fear among the citizens:

"People would hastily cross the road to avoid having to speak to me. The fact that my brother-in-law Swamy was a member of the Jana Sangh and that both Virendra and I had at one time worked for the Motherland [a Jana Sangh mouthpiece] made us undesirable people to mix with.... Most people wanted to play safe and were scared they would earn a black mark if seen associating with those known to be opposed to the Emergency." (74)

Emergency rule was Kafkaesque in its concoctions of absurd pretentions and petty demands. There is a comical account of blundering and bumbling policemen:

"Virendra and I both had separate sets of sleuths following us, which made it difficult for us to carry out our professional duties. I travelled by bus and the police followed in a motorcycle and a car." And, then, there is this deadly sentence: "they assured us they would not be using any third-degree methods [against Virendra]."

Resistance to the Emergency built life-long political reputations. Though Coomi's account reflects badly on many (like Naveen Chawla, who went on to become the Chief Election Commissioner), she carefully avoids drawing any lessons or parallels now that a personality cult is being crafted around another prime minister.