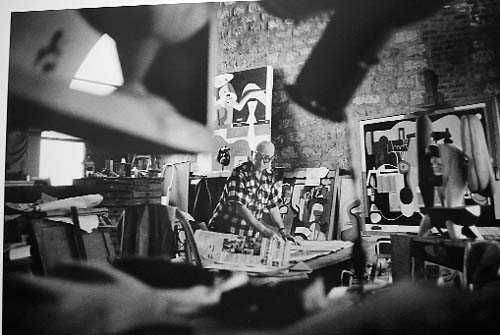

Le Corbusier in his studio. Photos courtesy: Museum of Modern Art, (MoMA) New York, 2013.

Rajnish Wattas

AS the world gets ready to celebrate Le Corbusier's 50th death anniversary on August 27, this year, two new books alleging the most iconic architect-planner of the 20th century and planner of Chandigarh to be a “militant fascist” and his work “inspired by Nazi art” is rather unfortunate. But not surprising, given the siren lure of sensationalism spiked with unexamined facts that marks our times.

In any case, the fact of Corbusier looking for work under the “Vichy Regime” — as the French collaborationist government was called — was never denied by him nor hidden. Many recent excellent biographies of the man, notably Modern Man by Antony Flint and Le Corbusier: A Life, by Nicholas Fox Webber, cover this dark phase and put it in perspective.

The real question is of brilliance and professional acumen of an artist and not the politics or ideology of his paymasters. Did the court painters of miniature paintings go around seeking commissions, pondering if they came from a noble, kind Pahari raja, a brutal Rajput ruler or the Mughal Court? Or for that matter did Michelangelo or Leonardo Di Vinci torment themselves with the ideology of their patrons? Neither were they expected to nor their work scrutinised under this lens.

During World War II, when France fell to the marching jackboots of Hitler's juggernaut across Europe, Gen Charles De Gaulle fled to London to raise the famous “Resistance”, leaving the World War I hero Martial Henri-Phillipe Petain, along with some other leaders called the “Vichy regime” after its’ headquarters at the small spa town — to shake hands with the Nazis to buy peace and let the rest of the French carry on with their lives and work.

Initially, Corbusier with his wife fled from Paris to a village, but finding himself unemployed, he soon got restless. He was introduced to Martial Petain through playwright Jean Giraudoux, who wanted Corbusier to undertake huge urban renewal and housing activity to rebuild the war-ravaged country. It was promising for a work-starved architect. Le Corbusier although by now had gained enormous fame across the world as a visionary thinker, urbanist and a pioneer of Modernism, but most of his projects either remained unbuilt or aborted — either for their radical concepts or fickle clients. His vision unfolded through his writings, observations and hypothetical “generic projects” as well as built ones, based on his insights on architecture and urbanism. His famous urban renewal schemes for Paris “Plan Voisin” in 1925 and before that in 1922 one for a "Contemporary City" for three million inhabitants just remained paper plans.

And he was convinced that the “establishment,” including “Beaux de arts,” and other traditionalists, did not want to address emerging issues of architecture and cities with the advent of the motor car, aeroplanes and the “machine age” demands on human habitats. A new vision, invention and paradigm was required, and he saw himself as a kind of architectural prophet for that. He had better solutions to offer. Even America's tycoons though feted and celebrated him during his 1930s visit, gave no commissions for his vertical city ideas, notwithstanding that he called the Manhattan skyscrapers as, “Grand Canyons of steel and stone!” Invited to nearly 30 lectures in numerous universities and schools of architecture in the US to packed halls — but no commissions.

Corbusier learnt his lesson: “Architects needed patrons not clients”. Coming back to the dark saga, Corbusier never ever made any public pronouncements of any political or ideological leanings, though privately in a letter to his mother did express a hope, “If Hitler kept his promises he can crown his life with remaking of Europe...solving real problems..end of speeches, meetings and sterility.” His professional setbacks, disappointments and almost maniac hunger to build and a divine drive for architecture, perhaps convinced him to take such a view. After the war, he certainly distanced himself from this dark dalliance and airbrushed the records, but he never ever had any political inclinations or ideological leanings towards fascism. The sum total of Le Corbusier was his work, his contribution to architecture, urban planning, art and writings at that point of time. No wonder, he was chosen for making India's city of tomorrow: Chandigarh. And admired by no less a person than by Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru who wanted the city to be, “unfettered by traditions of the past...symbolic of India's freedom”. Today Chandigarh —not withstanding its flaws —has stood the test of time. A city planned for 5 lakh population holds 12 lakh people. Along with burgeoning extensions of Mohali, Panchkula, Mullanpur falling in bordering Punjab and Haryana, it is projected to become an urban complex of 45 lakh people by 2030!

For the making of Chandigarh, Corbusier lived in tents or makeshift resthouses under baking sun and dust storms, all for a pittance. His Indian associates recall his concern for the human aspect always in his work. He would go over to nearby villages to sketch mud huts, vibrant folk art, carts, buffaloes and bullocks! He later translated some inspirational forms like the piercing bullock horns into a canopy shape for a portico in front of the Assembly building and painted its huge door personally with motifs of sun, animals, nature and cosmos — affirming his connect with the timeless Indian civilisation and its placid bucolic life. He was fascinated by the etchings drawn by rustic village labourers on wet concrete surfaces of parrots, peacocks, fish etc. and used them as bas-relief for his building facades. His monument of the Open Hand in the Capitol Complex —his greatest realised work — is derived from his deep belief in peace for the war-torn world. The Open Hand stands for the message: “Open to give and Open to receive.” Personally, he was almost monastic and hermit-like in real life and lived only to work, to paint, write, make buildings. When he died, his worldly possessions were mostly the compendium of his work: 32,000 architecture drawings, 8,000 art drawings, 200 paintings, and 1.5 million memos and other documents, which he bequeathed to posterity. Could such man ever be a Nazi at heart?

The writer, the former principal of the Chandigarh College of Architecture, is an author and architectural critic.