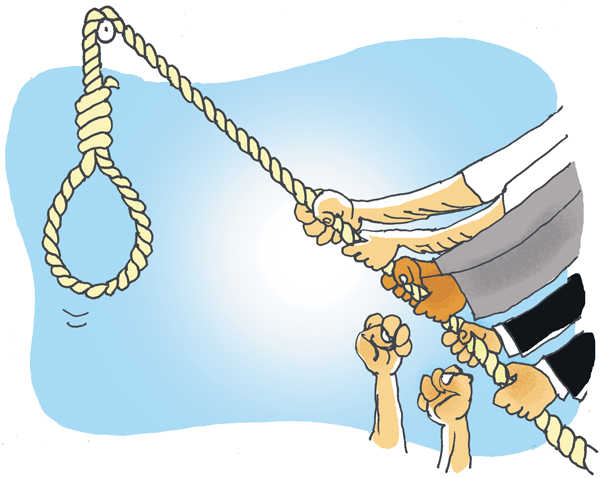

Illustration by Sandeep Joshi

Harish Khare

THIS Thursday was a particularly painful day in the life of the young Indian State. That day we observed two deaths — of two very different Muslims. In the Nagpur Central Jail, in the weehours we hanged a man named Yakub Abdul Razak Memon. We exulted, silently and collectively. A few hours later, in Rameswaram, we buried another man named Avul Pakir Jainulabdeen Abdul Kalam. With fanfare and ritual ceremony of full state honours. No news camera was allowed to record the death in Nagpur. The Rameswaram burial took place in the full glare of klieg lights. Strangely enough, we seem to think that as a nation we are entitled to a sense of satisfaction on both counts.

At Nagpur, we pretended we were making a simple but an unequivocal and much-needed statement. A modern State is obliged to maintain peace and to protect its citizens against physical harm and death, both from internal and external sources. A corollary follows. As the custodian of order, the State and its functionaries are duty bound to punish those who take it upon themselves to hurt or kill fellow citizens. In seeking a death by hanging for Yakub Memon, we can experience a sense of gratification of having upheld a fundamental principle and discharged a basic duty. We like to believe that Yakub’s religious identity is simply coincidental.

At Rameswaram, we undertook to make another statement: India is a secular polity, and we can take considerable pride that even its high offices are open to men and women from the minority communities. We can pretend that excellence and achievement alone count — and, not the religious affiliation — in the matter of reward and punishment. We can rest on our oars that we have built up a merit-based civic society and a secular political order.

At Nagpur, our narrative insisted on re-asserting the Indian State’s macho credentials. India is not a soft state; we are not a banana republic and that we are more than capable of meting out retribution to all those who take liberties with our laws and our order. At Rameswaram, we have allowed ourselves to be told that we have reiterated the Indian State’s secular credentials. Both arguments are over-statements because both seek to disguise the un-elevating political calculations at work. The two endings — Yakub’s death, attended by only the hangman’s accoutrements, and Kalam’s burial, serenaded by the military trumpeter —remind us of our lingering, almost institutionalised, illiberalism.

In Yakub’s case, we have chosen to obliterate from our collective memory the context of his crime. Let us recall that the context was the demolition of Babri Masjid. And, that demolition was not a stray incident. It was part of a well thought-out and a well-executed strategy of political mobilisation and consolidation. LK Advani was its high priest, who had embarked on a rath yatra, from Somnath to Ayodhya, leaving behind him a trail of violence and intimidation. In simple terms, the strategy was anchored in a calculation to move and motivate the Hindu majority to put — to use Advani’s evocative phrase — “Babur ki aulaad” — in their place. The subtext was to tell the minorities to fall in line with the demands and preferences of the majority community. Yakub and his co-conspirators were misguided enough to think that they could resist by violent means the Advani demarche. Yakub and his gang inflicted indiscriminate death on innocent citizens. The balance of guilt — between Advani and others, on one side and the Memons and their cohorts, on the other — has never been scaled right.

There was also a context to Kalam’s elevation to the highest office in the Republic. And that context was the then Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee’s utter helplessness in the face of the horrible, horrible 2002 anti-Muslim riots in Gujarat. As Prime Minister, Vajpayee had found himself totally out-manoeuvred and out-voted by his own senior party colleagues when he tried to make the case that the then Chief Minister Narendra Modi had failed to perform his rajdharma. Vajpayee wanted the principle of political accountability to be upheld. His invocation of rajdharma, a basic principle of statecraft, was spurned. On the rebound, the Vajpayee faction had brought in Abdul Kalam as a way of cleansing India’s soiled image. And Kalam had fitted the bill, in more than one way. He was quite willing to be a part of an elaborate ruse to extricate us from our collective guilt over the Gujarat riots. He was a pliant occupant of Rashtrapati Bhavan during NDA rule. For example, he was more than happy to unveil Veer Savarkar’s portrait in the Central Hall of Parliament. His predecessor, KR Narayanan, had pointedly declined to do so.

We take considerable satisfaction that our judicial process is robust and liberal enough to uphold the principles and practices of a just society. Indeed, Yakub and his lawyers were allowed to exhaust every single legal remedy and relief. The sturdiness of our legal system is not in question. At stake, rather, is the Indian polity’s fairness, its sense of ethics and virtue. On the other hand, we seem to be forgetting that the same much-vaunted legal process is yet to be consummated in another case — the Babri Masjid demolition case against Advani and others.

The culpability in the Babri Masjid demolition case has been explained away, even celebrated, as a “political” misdemeanour, at best. Yakub’s crime was isolated in the silo of individual culpability and he was punished. His antagonist, at least symbolically, Advani was and remains protected by Black Cat commandos, the most ubiquitous symbol of the Indian State.

There is an unstated yet very discernible sense of catharsis in Yakub’s hanging. A certain history is irretrievably mixed up in that little gory rite of death in the Nagpur Central Jail. Yakub was offering us a chance to redeem ourselves. We declined. Instead, we allowed ourselves to wallow in the meretriciousness of an insistent vengeance and retribution. The Ujjal Nikkam school of maximum punitive response trumped our imperfect liberalism.

At Nagpur, we lost an opportunity to settle one of the most difficult equations — the terms of co-existence between the majority and the minorities. This equation was, is and will always remain critical to the health of our polity and to the efficacy of the Indian State. The military salutes and ceremony at Rameswaram will not compensate for the Nagpur blood-thirstiness. As a nation, we must feel poorer and as a state, we are saddled with a self-inflicted vulnerability.