S Nihal Singh

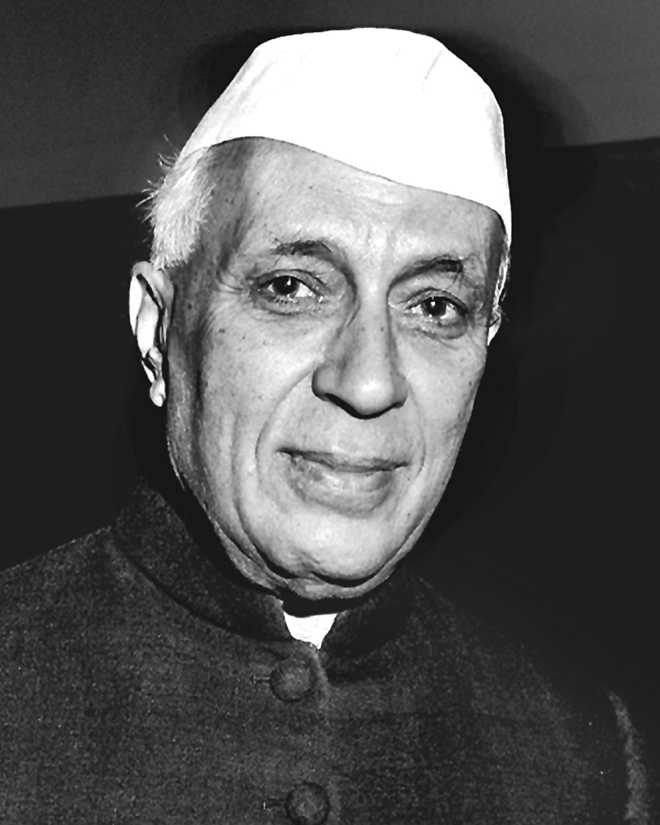

AS we observe Jawaharlal Nehru’s birth anniversary today, one facet of his many-sided personality stands out. He is above all the maker of modern democratic India as we know it even as it is sought to be altered by the new dispensation that rules the country.

State control of industry and non-alignment might have outlived their usefulness. But they were essential tools of nation-building in those early days of Independence. And they served the important purpose of kick-starting development. Besides, a militarily weak country espoused non-alignment as a means of seeking an independent course in foreign policy when nations near and farther afield chose to bend.

As a parliamentary correspondent, I watched Nehru from the press gallery. He was punctilious in attending the two Houses, shepherding his flock in the art of persuasive speech and deferring to the Opposition benches, despite their paltry representation. Those were the days of intellectual giants and fluent speakers keeping the country and the Press agog.

Nehru knew that only by example could he embed the habit of parliamentary practice in a bewildering assortment of representatives, many from a rural background. Doubtless, Nehru and many of his colleagues represented a Western-influenced elite seeking to impose the best forms of governance they had imbibed in their years of learning in the West. But Nehru’s genius was to adapt the best in Western practices to the Indian setting.

Like all great men, Nehru was a visionary and a romantic. While high dams and steel mills were at the heart of modernising India, he shared his thoughts with the people at large, often through soliloquies that went over the heads of his listeners. But such was the bond that existed between the born aristocrat and the humble villager that the people took him on trust. He was their beloved Panditji.

Mahatma Gandhi, with his unerring political instinct, designated him the country’s future leader because of the suffering he and his family had undergone, together with many others, but also because of his abiding concern for building the future and his chemistry with people. Although Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel, the borrowed icon of the Bharatiya Janata Party today, was the shrewder and more hard-headed ruler and administrator, the Mahatma knew that Nehru was the nation’s conscience-keeper.

India and non-alignment were a perfect fit, as for other emerging countries, because it was the only sane policy for militarily weak nations that sought to maintain autonomy in foreign policy. Its concepts might sound quaint today, but in those early days of Independence, they buttressed the idea of freedom in a predatory world in the Cold War era.

Nation-building was at the heart of Nehru’s activities across a wide field — in planning, in community development, in scientific research and development of atomic energy. He realised even as the bloody partition that foreshadowed the division of the subcontinent that unlike Pakistan that had opted for a Muslim land, India would remain a country of many religions and it was his continuing endeavour to make the large Muslim majority that remained behind feel at home. The turmoil we witness today following the BJP’s attempt to change the idea of India as it has evolved over 67-odd years is testimony to the wisdom of Nehru’s vision.

For Nehru, several concepts were moulded into the idea of India: development, a secular order, the uplift of the poor, abolishing illiteracy. He felt that even as the poor and the illiterate should be moved up, India should reach for the highest level of science and technology. Long before the decision to build a bomb was taken, Dr Homi Bhabha, the czar of Indian space research, had told me that he needed just one year to make the bomb. Nuclear research for Nehru was entirely for peaceful purposes providing energy without polluting the environment.

Nehru had his faults, which manifested themselves in two main areas. He was perhaps too influenced by Lord Louis Mounbatten, who was asked to stay on as independent India’s Governor-General, and his wife Edwina in seeking United Nations intervention on the Kashmir issue, with unwelcome results we are familiar with. But his greatest mistake was in relation to China.

Nehru, we must remember, had built up a whole concept of Asian solidarity in which the two Asian giants, India and China, would play the stellar role in the brave new world. Even as he played the big brother in introducing China’s Zhou Enlai to the non-aligned world in Bandung, a role Beijing resented, he was blind to the telltale signs that were building up, in Aksai Chin and elsewhere.

The Chinese military incursion into India shattered the vital Asian pillar of Nehru’s foreign policy. He was forced into the ignominy of seeking American military assistance; the response from the latter was niggardly. With the unilateral Chinese withdrawal after teaching India a lesson, he tried to recover his balance, but he never fully recovered from this great tragedy, occurring as it did towards the end of his life. I was in Vientiane, Laos on my South-east Asia beat the day Nehru died, commemorated at a modest event in the Indian embassy.

Looking back, Nehru was a giant who strode the Indian stage at a propitious time. He not only won freedom, in the idiom of his colleague Maulana Abul Kalam Azad, but also laid the first solid bricks in the edifice of a newly-independent nation. That India has weathered wars and other shocks in the succeeding decades is an abiding tribute to his vision and persistence. But the greatest tribute we can pay Nehru is to buttress the democratic India he has bequeathed us.

Yes, there are many warts in the Indian concept of democracy. Its most trying moment was, of course, the Emergency imposed by his daughter Indira in the mid-seventies. Its saving grace was that she was forced to call elections in which she was routed only to be regenerated later.

It remains to be seen how far Prime Minister Narendra Modi and his Sangh Parivar will go in demolishing Nehru’s idea of India. The attempt marks a danger signal for the country.