Taking a stand: India’s vote on Ukraine is an assertion of its independent foreign policy.

MK Bhadrakumar

UKRAINE and Palestine may seem two vastly different regional conflicts. Yet, last week, from the perspective of India’s foreign policies, just as between Mars and Venus or between the rose bushes in the backyard, a spatial relationship appeared. The votes that India cast at the United Nations General Assembly in New York on successive days last week regarding the resolutions on Ukraine and Jerusalem, respectively, were anything but routine. After a long while, South Block displayed a remarkable understanding of spatial awareness.

The retrieval of implicit memory in foreign policy always underscores a political decision. How far the US President Donald Trump’s National Security Strategy (NSS) 2017, which he unveiled last Monday in Washington, gave impetus to overcome the challenge of amnesia — depending on how one looks at it — may never be known, but the chances are that it most certainly would have. Between the two resolutions, the one on Palestine received far greater attention in the Indian media, thanks to the US ambassador to the UN, Nikki Haley, who had openly threatened that she’d be “taking names” of countries that voted to reject Trump’s recognition of Jerusalem as the capital of Israel and report to her President who would “take this vote personally”, and, furthermore, that Washington would remember which countries “disrespected” America by voting against its diktat.

Unsurprisingly, when PM Modi showed “disrespect” to Trump, it became big news for the Indian media. But India has taken this open stance on Jerusalem with such disarming candour that the risk involved by snubbing Haley’s hard-power diplomacy is actually minimal.

However, it was the vote that India cast regarding Ukraine on Wednesday — against a Western resolution condemning Russia for human rights violations in Crimea and Sevastopol — that takes the breath away. This needs explaining. For a start, anyone who anticipated the inevitability of post-Soviet Russia’s resurgence on the world stage would have instinctively sensed that it would be eventually over the status of Ukraine, where memory mixed with desire, that the epic struggle for the control of the “heartland” — to borrow the expression from Sir Halford John Mackinder’s controversial theory — would mutate and resume.

Mackinder’s theory significantly influenced the US’ strategic thinking toward the former Soviet Union. By an interesting coincidence, on December 12, Georgetown University in Washington brought out as part of its Russia Program a stunning collection of declassified US, Soviet, German, British and French documents showing a cascade of assurances about Russian security held out to Mikhail Gorbachev and other officials in Moscow throughout the process of German unification in 1990 and on into 1991, devolving upon the future of NATO. The archival materials substantiate conclusively that Gorbachev and others in the Kremlin were led to believe that the US wouldn’t take advantage of the situation with an eastward expansion of NATO.

None other than US Secretary of State James Baker III at a meeting on February 9, 1990, in Moscow, assured Gorbachev that “neither the President nor I intend to extract any unilateral advantages from the processes that are taking place”, and that the Americans understood that “not only for the Soviet Union but for other European countries as well it is important to have guarantees that if the United States keeps its presence in Germany within the framework of NATO, not an inch of NATO’s present military jurisdiction will spread in an eastern direction.” Helmut Kohl, then German Chancellor, who met Gorbachev the next day repeated much of the same thing that Baker did. And Gorbachev agreed in principle for German unification on that understanding. (Kohl later wrote in his memoirs that he couldn’t sleep that night and walked all night around Moscow.)

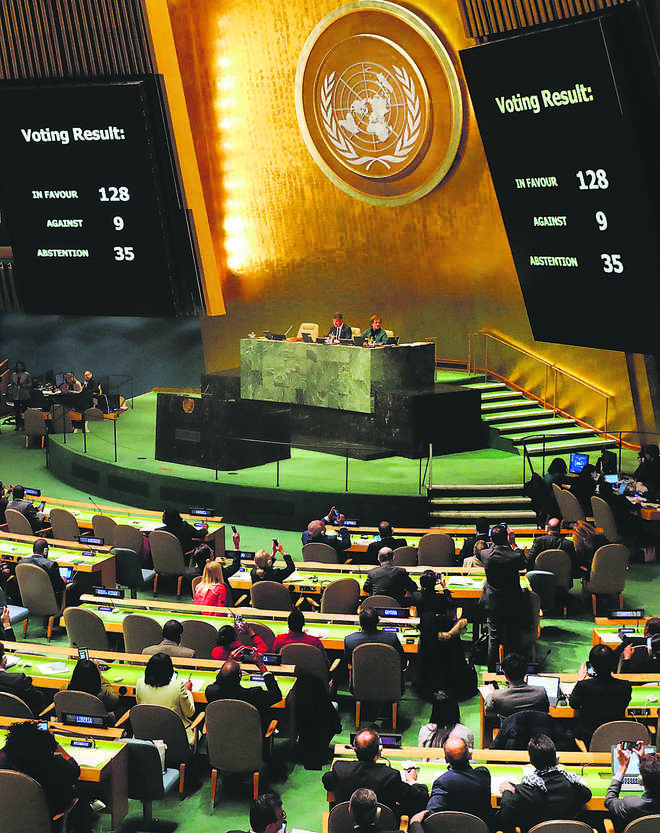

Alas, the strategic discourses by Indian pundits are limited to “Indo-Pacific” as they see only a sliver of the sky from the bottom of the well. But, South Block with its institutional memory would know the profound implications of the Indian support for Russia over the resolution regarding Crimea at the UN last week. India had an option to abstain, as indeed 76 countries did. But instead, India decided to stand shoulder to shoulder with Russia as one of the 25 countries to do so by casting its vote to reject the West’s resolution — alongside China, Iran, Cuba, Nicaragua, Venezuela, North Korea, among others.

The NATO has now expanded through former Warsaw Pact territories and Baltic States to reach the borders of Russia. Suffice to say, the locus of world politics still lies in Eurasia — not in the South China Sea. Trump’s NSS visualises the challenge of China and Russia as “fundamentally political contests” but it is the Russian military capabilities, including nuclear systems, that remain “the most significant existential threat to the United States” and it is in Eurasia that “the risk of conflict… is growing”. Elsewhere, China may seek to “displace” the US in the Indo-Pacific region but its “intentions are not necessarily fixed” and the US also stands ready to cooperate across areas of mutual interest.

The NSS says that the 19th century “great power competition (has) returned” and the world has become "actually an arena of continuous competition”. In the final analysis, the US upholds “the central role of power in international politics”. What emerges is that the US’ global strategy has narrowed down to retaining its “overmatch” — global dominance — at a time when “US advantages are shrinking” and the task ahead is that American military superiority endures in an international milieu where American prosperity and security is “challenged by an economic competition playing out in a broader strategic context”.

India cannot but militate against Trump’s NSS, which is antithetical to the aspiration that its foreign policies embody. It is a confrontational doctrine, which locks it in as a subaltern in the mobilisation to shore up American prosperity from erosion. The NSS comes as a rude shock because its singular message is that the US cannot countenance other countries becoming major powers. It defines Indo-Pacific as the “region which stretches from the west coast of India to the western shores” of the US! And it is the ASEAN and APEC that “remain centrepieces of the Indo-Pacific’s regional architecture and platforms”. Meanwhile, the document admits, “We seek an American presence in the (South and Central Asian) region”. The bottom line is the NSS’ unwarranted apocalyptic scenario of an India-Pakistan nuclear war, which requires that the US paid “consistent diplomatic attention” — American intervention. India’s vote on Ukraine is a timely assertion of our time-tested relationship with Russia and our independent foreign policy.

The writer is a former ambassador