Bending law: The arrest and later release of ‘stone-pelters’ in J-K violates legal sanctity.

Nirmal Sandhu

HARYANA, Himachal Pradesh, J&K and Punjab have one thing in common: the Chief Ministers in these states are recommending withdrawal of criminal and corruption cases. Driven by political expediency, they, it seems, have not thought through the possible consequences. The police, prosecution or court finding someone innocent on the basis of available evidence is different from politicians deciding who is guilty and who is not.

Their action may encourage law-breaking and further criminalise politics as well as the polity. It is contrary to the Supreme Court guidelines, violates the constitutional guarantee of equality before the law and amounts to interference in the independent functioning of the judiciary. Out-of-turn political acquittals induce resentment. Prisoners with political connections are more equal than others.

In a 2014 case filed by Gold Quest International, a company, the Supreme Court ruled that “an FIR can be quashed under Section 482, CrPC, and Article 226 of the Constitution in disputes which are substantially matrimonial in nature, or the civil property disputes with criminal facets, if the parties have entered into (a) settlement, and it has become clear that there are no chances of conviction”.

The court clarified that this would not apply in cases of rape, murder, robbery, drugs, dacoity or cases under the Prevention of Corruption Act. Most FIR cancellation moves made by the CMs relate to serious crimes and corruption.

Soon after taking charge, Himachal’s Jai Ram Thakur jumped to the rescue of Anurag Thakur, MP, with the familiar “political vendetta” defence. There are serious cases against him under the provisions of cheating, criminal conspiracy and the Prevention of Corruption Act. Apparently without bothering to look at the evidence, the CM has passed the “not guilty” verdict in favour of Anurag Thakur even though the state high court had earlier refused to stay his trial. Obviously Jai Ram Thakur is trying to be on the right side of the influential Dhumal family.

Haryana’s Manohar Lal Khattar once again succumbed to Jat threats recently, just to have a trouble-free Amit Shah rally. He was not sure the state power he wielded could ensure peace. The CM’s weak-kneed approach towards those charged with looting and burning public and private property has dismayed every law-abiding citizen. It is close to condoning mass violence. He badly needed to make amends for past blunders by firmly taking a stand that regardless of their number and nuisance capacity, violent protesters would be sternly dealt with.

In Kashmir the coalition government is set to secure the release of as many as 9,730 “stone-pelters” it had earlier portrayed as “anti-national”. J&K is not a normal state and the government has no clue how to restore peace and which solution might work. Excesses have happened and these drove hordes of students out of classrooms. Cases should not have been registered in the first place. A non-discriminatory enforcement of the rule of law could have shrunk the space for stone-throwing and militancy. But now the sanctity of the legal process should not be violated at the political level. Courts do take a lenient view of first-time offenders. Political rescue may send out a wrong signal.

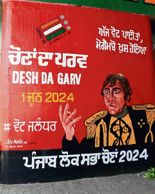

In Punjab a former judge is scrutinising “false” cases against Congressmen and others. Erring policemen are being punished, while politicians who got innocents in jail are being spared. Ideally to avoid political misuse of the police the force should be depoliticised. In the Prakash Singh case the Supreme Court recommended reforms that included a permanent authority to hear complaints against the police. None of that, however, seems to interest the Chief Minister. Forget Capt Amarinder Singh, no CM would like to shed control over the police and opt for law-based policing that treats everyone equally.

Framing of innocents is common. Maybe the punishment prescribed is not deterrent enough. Judicial delays also bother everyone. Jails are swarmed with inmates awaiting trial for long years. Instead of limiting their intervention to party loyalists or sections like Jats and stone-pelters, the CMs could work to energise the easy-going prosecution, rein in litigation-prone officials and help courts clear the backlog by investing more in judicial infrastructure. But the CMs won’t fix systemic loopholes. That is not in their interest. The CMs are offering bailouts as a trade-off for political support or peace.

Though courts work independently, CMs can sometime render them helpless. They go by evidence presented by prosecution. We have seen investigating officers backtracking, witnesses turning hostile and district attorneys who were trying hard till the other day to send the accused to jail suddenly finding new proof of innocence of the accused. Courts just fret and fume but can do little beyond passing strictures.

We have seen all this in the disproportionate asset cases against the Badals and expect a repeat performance in the corruption cases against Capt Amarinder Singh. Both have used political power to manipulate the system to their advantage. Badal is very generous — but only at the taxpayers’ expense. He doled out grants to panchayats, liberally and illegally — illegally because such grants do not get audited. The Captain is also very helpful — helpful to those close to him and who are politically useful. Bypassing the set procedures, both have handed over jobs to favourites. Distributing favours is a feudal tendency that comes naturally to both. Withdrawal of cases is part of that mindset. The rule of law is not an issue.

From the village sarpanch to the CM, no politician wants the system to work without his intervention. If things get done in offices or services get delivered in the normal course that would reduce their usefulness and cut citizens’ dependence on them. That is politically undesirable.

Patronage distribution requires centralised decision-making. That has its advantages but can backfire at times as it happened in Haryana. When the state burnt during the Jat agitation, district-level officials waited for orders from above. Under the good old rules of administration they would have acted on their own and controlled the volatile situation. Thus instead of letting the established system work, Khattar ended up nationally advertising his incompetence.

India is fast becoming what political scientists call “a neo-patrimonial state”, where the top leader disburses favours like the king in the past. Power is used for self-enrichment at every possible level. Tragically, we have got used to it or part of it. We still have a lot of distance to travel towards a modern democratic state in which citizens’ interaction with the government and its institutions is impersonal and government machinery delivers services like security, justice, education and healthcare, regardless of who is at the helm.