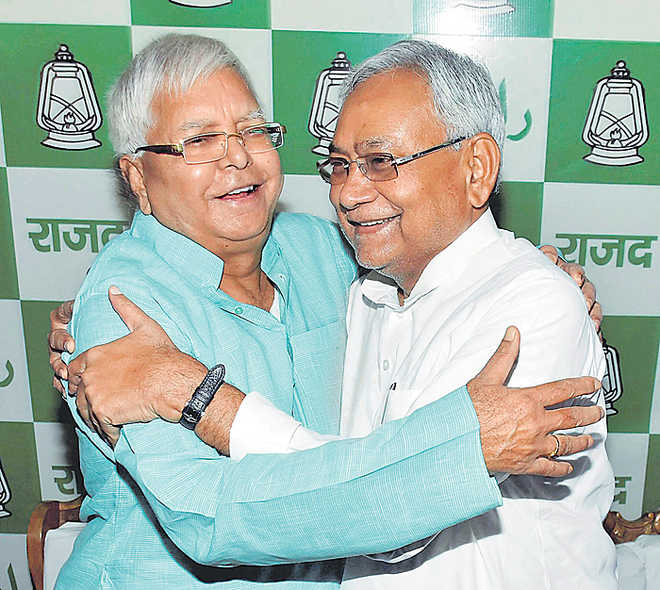

Letting go: Nitish Kumar’s role as CM was being constantly undermined.

Shaibal Gupta

THE fall of the Mahagathbandhan government in Bihar is a tragic affair. It symbolises all the ills that have afflicted the ‘social justice’ movement in Bihar. The movement emerged from the womb of the powerful ‘socialist movement’. After the ideological epicentre of the socialist movement was devoured by the JP movement, the social justice movement did play an important role in plebian ethos. Unfortunately, the movement later degenerated when proactive pursuit of ‘positive discrimination’ created a caste-based empire, with the most undemocratic satrap heading these outfits.

When Lalu Prasad and Nitish Kumar joined hands for the 2015 Assembly election, in spite of their acrimonious relationship earlier, it seemed that social justice movement will not only get a new lease of life, but will also get reinvented. Lalu with his political capital and Nitish with his administrative acumen were expected to give a fresh lease of life to Bihar’s development strategy. But unfortunately, the strain in the Mahagathbandhan surfaced from the very first day when Lalu’s two sons, both greenhorn in politics, were appointed ministers, ignoring senior party functionaries of the RJD. While the younger son, Deputy CM Tejashwi Prasad Yadav functioned relatively better, the elder one turned out to be a disaster.

In the two terms of the NDA earlier, Nitish had full freedom to function and had kept the ministers on tenterhook. This not only helped him streamline the ramshackle administration, but also resurrected the state. In the process, Nitish had, indeed, emerged as a huge brand in the business of governance. In his third stint as part of the Mahagathbandhan, however, the Chief Minister felt disadvantaged. There was always a reminder from the RJD minions that they were a bigger party than the JD(U). Further, Rabri Devi often suggested that being the single-largest party in the Mahagathbandhan, Tejashwi should take over the reigns of the government. Nitish, who takes any administrative and political agenda very seriously, felt this continuous snipping was getting increasingly intolerable. Whenever recalcitrant RJD workers created problems for Nitish, they were not reprimanded by their senior leadership. When Shahabuddin was released from Bhagalpur jail on bail, he conveyed in a demonstrative manner that the state machinery is at his command and the role of the CM was merely incidental. Shahabuddin’s utterances were supported by the RJD high command, with a deliberate strategy to insult Nitish.

However, the Mahagathbandhan could have continued, in spite of its limitations, thanks to its comfortable majority. But once the spate of scandals involving Lalu’s family was made open, it was the last straw on the coalition’s back. Assuming that Lalu had learnt a lesson from his conviction under the fodder scam, it was expected that his young sons will be leading a reinvented lifestyle. Under the mentorship of Nitish, they could be groomed into someone who will ultimately take over the reign of the state. But unfortunately, almost every immediate member of the Lalu family got embroiled into the crisis.

Bihar is the poorest state in India, with very low public investment earlier, but the extent of leakages in the public spending here was one of the highest. This started in the immediate post-Independence years. Indeed, buccaneering accumulation and resultant consumption has become a way of life in the state for long. Later, during Lalu’s period, this pattern of accumulation got perfected. Leave alone any stigma against such practices, those who indulged in it were actually held with awe and admiration.

Quite expectedly, these accumulations were used not only for conspicuous consumption, but also for tremendous political and criminal ramifications. Over the years, accumulation through corruption had gradually reached a cancerous proportion.

With democratisation and empowerment of people, it is only recently that corruption is now viewed with revulsion and disdain. The powerful constituency which was created by corruption and which had forestalled all development in the state is now in retreat. Nitish essentially choreographed this strategy.

As the decisive steps to check corruption in Bihar, details of assets of public functionaries were ordered to be put on the official website of the state government. The Local Area Development Fund for legislators, a great source of corruption, was abolished. Further, the bold initiative of enacting two formidable laws — Prevention of Corruption Act and Right to Service Act — has changed the rent-seeking tendency of public functionaries in a decisive manner. The first relates to the confiscation of such property by the state government, which are disproportionate to an individual’s income from known sources.

The second stipulates a time limit for providing service by the state functionaries to the citizens, so that rent-seeking can be prevented. Earlier, rent-seekers could accumulate with gay abandon and even the most blatant rent-earners got either inconsequential censure or, at best, a suspension order. Additionally, in the name of right to private property, their illegal properties were not touched. Both these laws are now acting as the sword of Damocles for the rent-seeking government functionaries.

One may also note that the leakages of public spending in Bihar had a peculiar character, not to be seen elsewhere in the country. Here the fund for government programmes, earmarked for either economic or social sectors, would be siphoned off for private accumulation right at the input stage. Thereafter, such buccaneering private accumulation will not get invested within the state, as was the case in Indonesia; instead, the amount would often be transferred outside, as was the case in the Philippines. With their limited knowledge of the capital market — domestic or international — the looted resources of the state were generally invested in the real estate in metropolitan cities.

In this backdrop, the battle against corruption could not have been pursued within the Mahagathbandhan. Its liquidation might be a setback to secularism, but secularism cannot be pursued at the altar of brazen corruption. The UPA-II failed in its effort to deflect the allegations of corruption. In the process, the Congress got wiped out and the BJP got massive majority. Simultaneously, the social base of secularism shrunk, because corruption was protected thoughtlessly.

The writer is member-secretary, Asian Development Research Institute