Harish Khare

THOUGH historians have serenaded Indira Gandhi for leading the nation to an unprecedented and enormously satisfying victory in 1971, she has been copiously castigated for 1975 (internal Emergency) and 1984 (Operation Bluestar). Yet it is her role in 1969 in forging the Indian National Congress as an instrument of the Indian State and as a platform of a politics of progressive centrism that remains vastly underappreciated. That linkage between the vitality of the Indian State and a progressive centre remains as valid today as it was in 1969.

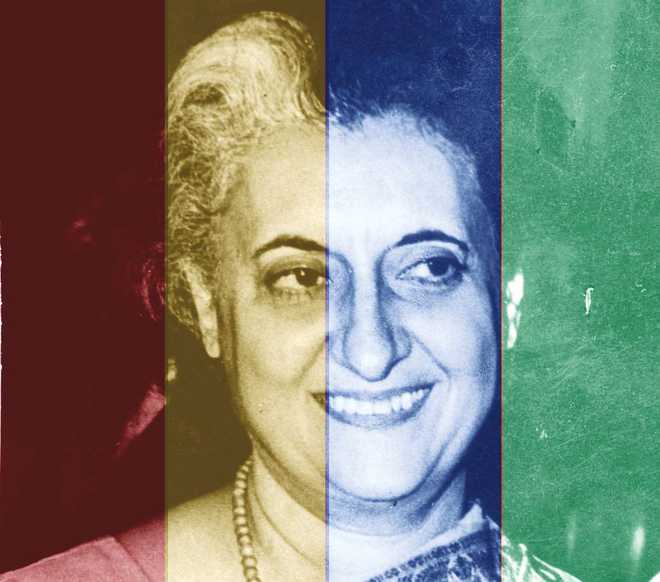

It is important to remember that Indira Gandhi was only 48 when circumstances propelled her to the prime ministerial gaddi. It is even more important to recall the context — domestic and international — in which she was called upon to lead a deeply troubled nation-state.

The 1962 conflict with China had not only demoralised the nation, it had also brought into disrepute Jawaharlal Nehru’s leadership; consequently, the Nehruvian consensus had come under severe contestation. While Nehru had decisively defeated the Hindu revivalist forces in the early years after Independence, it was inevitable that his decade-old attempt to make India into a modern democratic nation, an egalitarian social order and an industrialised economy would invite reactions and challenges. That was and remains the law of history. Every policy paradigm has consequences; there are winners and losers, and losers try to regroup to challenge the new winners. Nehru had managed to initiate the new nation into experiencing a hitherto unknown sense of collective equanimity; he gave every Indian a feel of national destiny, and had excited popular imagination with promise of a partnership in building a fair, just and accommodative political order.

The 1965 conflict with Pakistan managed to paper over the nation-state's fragility, so disconcertingly brought to the fore in January 1965 when anti-Hindi passions and violence in the South nearly sank the national unity boat. The 1962 and 1965 conflicts also brought India face to face with economic bankruptcy; we even did not have, it seemed, enough food to feed our people. Dissatisfaction, discontent and disruption were writ large on our national blackboard. The Indian polity was buffeted both from the extreme Left and the unyieldingly feudal Right. The Naxalites had violently made their presence felt in parts of India; at the other extreme, the old princely order had recovered its breath and was snipping at the heels of democratic India. The carefully nurtured Nehruvian state order which had produced political stability and social harmony was under assault.

The 1967 general election produced a very consequential stalemate at the heart of the Indian polity. Political parties on the Left (CPM and CPI) and the Right (Swatantra Party and Jan Sangh) made spectacular gains at the expense of the Indian National Congress. There could be no doubt that the Nehruvian consensus was under siege; indeed, taking advantage of the political and intellectual confusion, the Supreme Court, led by Chief Justice Subba Rao, had waded in [the Golaknath case] to declare right to property a sacrosanct entitlement. An empowered and emboldened Right rewarded Justice Subba Rao with a nomination in the contest for the office of the President of India.

The 1967 general election also exposed the fault-lines and frailties in the Indian National Congress and how it was losing its usefulness as the principal political instrument of the Indian State; the Congress’ primary task was to garner legitimacy and democratic respectability for the new state-order but the party was faltering in that role. It became all too obvious that the party bosses had choked the organisation of its political creativity. This bossism had drained the organisation of all its moral capital. The Atulya Ghoshes, the SK Patils, the CB Guptas, the Kamrajs, had all seen to it that the Congress shut its doors to the emerging new social classes with demanding and clashing aspirations. The Congress had ceased to be a political party of mobilisation; instead, it had become the plaything of vested interests and status quo.

The 1967 general election also confronted Indira Gandhi with a dharma-sankat. It were the party bosses who had installed her as the prime minister after Lal Bahadur Shastri’s sudden demise on that cold wintry night in faraway Tashkent in January 1966. She was beholden to them but it must also have become painfully clear to her that these very party bosses were not ideological men and had little interest in nursing the Nehruvian consensus back to its robust good health. What was equally evident was that these party bosses were oblivious to the resistance the Indian State faced from forces, within and outside. In other words, the much-touted and much-admired “Congress system” had run out of steam.

It is difficult to say when it dawned upon her that the Congress party bosses had to be confronted if the party were to rediscover its progressive centre and the Indian State were to regain its nerve as well as its verve. It is not that Indira Gandhi had suddenly become a bomb-throwing revolutionary; it was just that perhaps she understood the call of history. Unlike her father, she did not possess an evolved intellectual mind; nor was she wedded to any kind of ideological dogma. Perhaps she had a primal feel and a political instinct to understand the Indian State’s obligation to its citizens and their hopes and fears.

By 1969, a Congress split had become inevitable. As it is, by 1967, the polity had run out of the space Nehruvian era had carved out for itself. Some kind of bloodbath could no longer be avoided; the only question was whether it could be accomplished peacefully. A much larger disruption and possible disintegration could still be avoided if the Congress was subjected to convulsions of change, and was constrained to rearrange its internal power structure so as to ensure a place of primacy for the progressive centrist core.

By 1969, Indira had willed herself to perform the primary leadership task in India: restoration to the Centre its progressive mojo. She could take on the party bosses only by enlisting the masses in her struggle with the forces of status quo. She initiated India into a phase of mass politics. And, inevitably, mass politics brought with it the temptation of personality cult and inculcated an impatience with institutional accountability; and, that paved the road with good intentions all the way to 1975.