Harish Khare

NITIN GADKARI has rightly earned the reputation of being “the only working” minister in the Narendra Modi government. Many of his colleagues may be inclined to contest this salutation, but he himself would have no quarrel with any dissenter — partly, because he is also the most level-headed political head in the Narendra Modi arrangement. Having been a national president of the Bharatiya Janata Party, he is fairly well versed in the dynamics of pan-Indian political and economic forces at work in our continental polity and probably knows that there are more than 11 shades of grey.

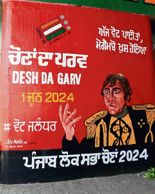

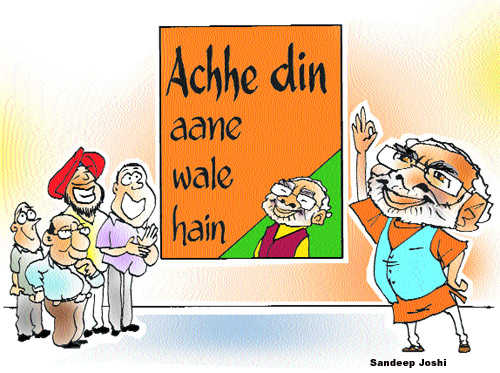

It was, therefore, rather courageous of Nitin Gadkari to have allowed himself to observe the other day on the achhe din promise made in the 2014 Lok Sabha campaign. He was reported to have diluted and distanced his government from the achhe din slogan, so prominently and so full-throatedly voiced by his party’s prime ministerial candidate. To be fair, Gadkari is not the first to backtrack on the promises made in 2014. It was the current BJP president who had, for example, pooh-poohed the election-time slogan of “fifteen lakh rupees in every Indian's pocket.” During the 2014 campaign, it need be recalled, the BJP and its prime ministerial mascot were mesmerising the masses and voters with a promise of bringing back the mountainous black money that the UPA government had allowed to fly away to the Swiss banks. The BJP president simply dismissed the tantalising promise as nothing more than an election-time jumla. Sorry folks, we simply did not mean it.

Gadkari’s demurral, however, is not deceitful. His argument, as reported in the media, was that in a vast, hugely over-populated country such as ours, with centuries of poverty and inequalities, there would always be oceans of unfulfilled dreams and ambitions, and that large swathes of society would continue to hunger and aspire for “better days.” When confronted with the query as to when the promised achhe din would be ushered in, Gadkari had rather tartly responded that the slogan had become a gale ki haddi. A colourful Hindi colloquial expression, but a perfect epigram for the Modi government’s dilemma: a promise that the government can neither disown nor deliver. What perhaps he meant was what a seasoned American political leader, Mario Cuomo, had once summed up as being the essence of modern-day democratic electoral contests: “You campaign in poetry, but you govern in prose.”

All democratically elected leaders face a fundamental conundrum. As an outsider, the challenger has an inherent advantage over the incumbent President or Prime Minister: unsaddled as he is with a record, the outsider happily sells — often, oversells — dreams, knowing full well that the voter would eventually feel short-changed. Yet, all outsiders make exaggerated promises because they sincerely believe that they would be able to bring dramatic changes in the way the society, the economy and the government were organised, and that such rearrangements would produce an overall satisfaction among the citizens and voters.

Once voted to power, the outsider comes face to face with the grim reality. Governance is routine, demanding, unglamorous, and boring. It is far more intoxicating for an Arvind Kejriwal to promise grandiloquently the eradication of corruption than to attend to mundane administrative tasks such as dealing with the outbreak of chikungunya or collection of piled-up garbage. It is far more exciting to be a Home Minister and fly in and out of Srinagar, strutting like a daroga to the nation than to be a Transport Minister or Rural Development Minister, attempting to solve the nitty-gritty of water, roads, power supply, etc.

This is a global phenomenon. Three decades ago, European political scientists and policy wonks had begun organising seminars on ‘disaffected democracies’. They concluded: Governance deficit was inherent and inevitable. Take, for example, the current turmoil in the United States. Last week, the United States Census Bureau released data which shows that the household incomes in the United States had registered a 5.2 per cent jump in 2015, which was the highest since 1967; yet the American presidential campaign is being driven by an intense sense of disaffection and populist anger, and President Obama has been judged a grand failure.

We in India are on a slightly different wicket. The 2014 achhe din campaign was packaged as a total rollback of the Congress raj, the dynasty, and everything else that was deemed to be part of the Nehruvian legacy and history. We were repeatedly and gratingly told that the ancien regime had perpetuated dysfunctional policies and personalities, prejudices and preferences, and come achhe din, this historic albatross around our national neck would disappear. The achhe din was also a promise of muscular governance. We all had a jolly good time, mocking at Manmohan Singh for being so soft-spoken; we merrily accused him of taking orders from Sonia Gandhi, and, we believed that the achhe din would stand instantly ushered in once the primacy of the Prime Minister’s Office was restored. In sum, the achhe din was not just a promise of a better economic deal, it was also an invitation to new efficacy and edge at home and abroad. It was as sweeping a promise of change as was Indira Gandhi’s 1971 slogan of garibi hatao.

In the early days, the PM himself had got carried away with his achhe din spiel, and was boastfully telling the audiences, at home and abroad, that the nation’s bad dream was finally over. Things have not — and, never do — turned out quite so rosily. Indira Gandhi discovered so for herself, just as Modi and his band of cheer-leaders are discovering for themselves now. The magician has no magic wand, it is only a sleight of hand.

Let there be no doubt about it: the gale ki haddi will keep making itself felt. This is the theme song of the 21st century. A new mismatch has got introduced in the equation: our citizens have the access to the same technological tools of denunciation and are exposed to the same habit of demonisation that pockmark the American political discourse, but our rulers — at the Centre and in the states —who have to govern and deliver are saddled with primitive capacities and outdated incompetencies. The gap between the election-time promise and the governing-time delivery will not that easily get narrowed down.

Disappointment is built-in in democratic governance. In order to distract the voter, the American and European leaders are resorting to xenophobia, uber nationalism, hyper-patriotism and minority-bashing. In the coming days, our leaders, too, would be constrained to find ways of distracting the public from its acute sense of having been taken for a ride. That could be a dangerous moment. That would be the time for the collective democratic energy to ensure that regression does not set in and our leaders are kept on an even keel.