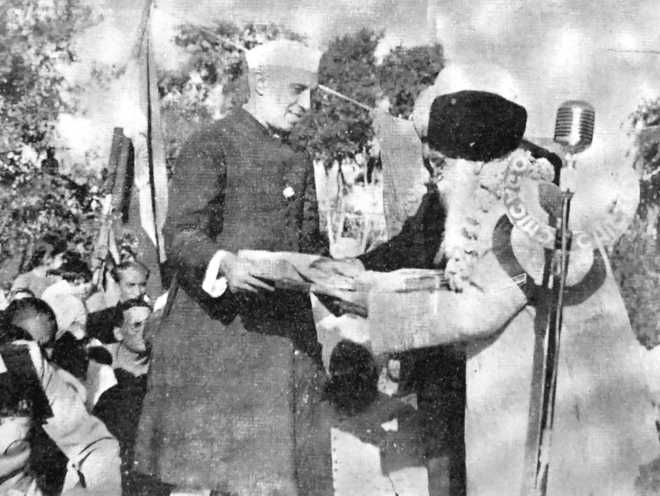

One-to-one: Baba Kharak Singh being honoured by Nehru, who admired his ‘iron will’.

Roopinder Singh

Why would Baba Kharak Singh be honoured? He was the man who represented the “politics of giving” and now is the time when “politics of taking” dominates. He had no redeeming feature in the form of a family that followed him into politics. The qualities that made Gandhi praise him, Nehru admire him and the British colonial administration treat him with wary respect in pre-Independent India were just the combination that made others uncomfortable in independent India, especially after the first decade or so, when there was a generational change.

Even as we are familiar with the process of appropriation of icons of the freedom struggle by various vested interests for political gains, Baba Kharak Singh was allowed to become a footnote in the struggle of Independence. Indeed, the feeble attempt by the SGPC to honour its second president on his 150 birth anniversary took place a day later, that too once this lapse had been highlighted in the columns of this paper. The Congress, as ever fixated on the family, was not expected to do anything, and it did not.

It obviously did not matter much that Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru had said: “In the days of our struggle for freedom, he was a pillar of strength and no threat of coercion could bend his iron will. By his example, he inspired innumerable persons.”

Yet, this very iron will made him a liability after Independence. The journey of this tall political leader, often called “The Uncrowned King of the Sikhs”, is interesting and illuminating. He represents a fine example of a committed Sikh and an idealistic political leader. One of the first graduates (1899) of Punjab University, Lahore, he had a comfortable lifestyle, as behove a member of a family in which the father and elder brother held the titles of Rai Bahadur. His involvement in the freedom struggle led to many trials and tribulations, but he never faltered in his convictions.

The “iron will” Nehru paid a tribute to was visible in during his five and a half years of incarceratation as a political prisoner in the notorious Dera Baba Ghazi Khan Jail. It was here that he led the morcha against the jailers who had ordered political prisoners to remove their Gandhi topi and in the case of the Sikhs, black turbans. These were worn as a symbol of protest against the Nankana Sahib tragedy, during which the British authorities had supported Mahant Narayan Dass against the Akali jathas. Firing by the mahant and his men on February 20, 1921, had resulted in the death of over a hundred Sikh protesters.

Baba Kharak Singh and other prisoners violated the ban during an inspection, in January 1923, by the Inspector General of Prisoners. The jailers retorted by forcibly removing the turban from Baba Kharak Singh’s head. This precipitated matters and all prisoners decided that they would not wear any clothes, except their undergarments.

Inducements, including permission only for Sikhs to wear turbans, threats, moving him to the “condemned cell” or the death row, all failed to move Baba Kharak Singh. He was released in 1927 when the Punjab Legislative Council unanimously passed a resolution to that effect.

Baba Kharak Singh’s determination had left an impact even earlier. He was elected the first President of the Shiromani Gurdwara Parbhandak Committee (SGPC) in 1921. In November that year, the Punjab Government ordered the Deputy Commissioner, Amritsar, to keep the custody of the keys of the toshakhana (treasury) of the Golden Temple. The SGPC protested and an agitation, Chhabiyan da Morcha, was launched.

As Rana Jang Bahadur Singh, a former Editor of The Tribune wrote: “Ultimately the proud ruling power had to bend before the iron will of the puissant Baba. The key was delivered to him at a public function by a representative of British imperialism. And, metaphorically speaking, with that key he eventually opened the gates of the temple of freedom. He became a general of the army of liberators in the Punjab and his life became a saga of sustained, valiant struggle.”

On January 17, 1922, the keys of the Golden Temple were handed back to Baba Kharak Singh. He and thousands of other political prisoners had been released earlier. Mahatma Gandhi, then “dictator” of the Indian National Congress, sent this message: “First decisive battle for India’s freedom won. Congratulations.”

After Independence, Baba Kharak Singh moved to Delhi. His grandson was allocated a house in lieu of the property the family had lost in Pakistan and here he lived till the last, believing that his work was done and refusing all positions, political or otherwise.

He would look back at his journey in public life. In 1912, the All-India Sikh Conference was held in Sialkot, and he was elected Chairman of the Reception Committee. In December 1919, he addressed the annual session of the Indian National Congress in Amritsar. He was elected, in February 1922, President of the Punjab Provincial Congress following the imprisonment of Lala Lajpat Rai. Mahatma Gandhi called it “an excellent choice”. Then he led agitations, as we have already discussed.

He was also watching independent India become different from the idealistic notion he had constructed. On July 10, 1949, he wrote: “It is a matter of genuine pride that India has become free and I pray to the Providence to bless my motherland with lasting prosperity and biding peace.

“But I regret to say that the lot of the common man has not much improved as it should have under the national government. Our PM (Nehru) is truly a great man worthy of the position that he holds, but I regret to observe that most of the things that he intends to do for the country’s good and many a declaration of policy he makes are not fully implemented by those who are doing the day-to-day administration.

“Black marketing, corruption, jobbery (fraudulent official transactions) and several other vices are rampant both in the administration as well as outside. I am afraid that if drastic steps are not taken immediately and if nothing substantial is done effectively to stem this vicious tide, our hard-won freedom will be of little use.”

Five decades after Independence, the man Khushwant Singh called “the most important Sikh character of the Indo-British history” is forgotten. His ideals, clarity of vision, his iron will and steadfast leadership at a very trying time make it imperative that we recognise the man and his ideals. In a vote-centric politics of today, such values hold little traction; in shaping a national conscience, they are invaluable.

PS: A few quotes have been reproduced from an earlier article by the author published in The Tribune.