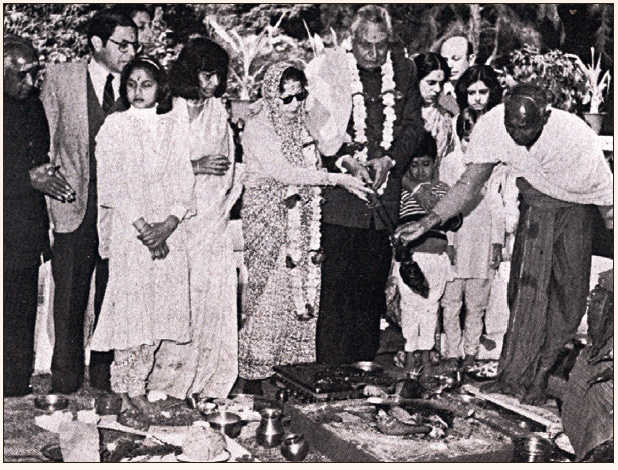

BK Nehru and wife Shobha celebrating their 5Oth wedding anniversary.

Gopalkrishna Gandhi

What are you writing now?” The question rang over the long distance phone from Kasauli. The voice spoke its age. But it had vitality. For Shobha Nehru was aged 108 when she posed the question to me last year. None of the usual ‘How are you?’ business, nothing of the painful ‘It has been a long time’ stuff. A straight question about what I was doing with my time. The arrow-tip directness was, quite simply, her.

As one who had seen her turn from when she was a vivacious fifty to a sedate sixty, then a stunning seventy to go on to being eighty, ninety and a hundred in perfect command of her faculties, I was in plain awe of her. She was, for me, Time’s quiet witness, much less vocal about what was witnessed than I hoped, more forgiving than was needed, but a witness. A grand witness.

Magdolna Friedman was re-named Shobha after she married Braj Kumar Nehru, a scion of scions from the Nehrus of Allahabad. Shobha she became, personifying grace and beauty, but she was really “Sakshi”, a witness to great proceedings, low intrigues, brutal happenings, sublime survivals.

Little changed in her with the years. Like a temple tree she stood her ground against Time, letting only her head of hair turn gently to a candy-floss auburn and her skin thin out to an almost translucent colourlessness. In what she said and in the way she said it there was that ‘something’ utterly self-assured and totally ‘sorted’ in Shobha Nehru , known to a wide circle of family and friends as Fori, that just could not be ignored. She italicised her spoken words, placing a certain emphasis, a distinct stress, on certain chosen words as she spoke that made them stand out.

The ‘Central European Jewess’, as her husband describes her in his brilliantly frank memoir “Nice Guys Finish Second”, had an unmistakable accent to her impeccable English. Her ‘d’s and ‘t’s were soft, and her ‘th’ , as in ‘death’, was always rolled into a ‘s’ – ‘dess’. This added to the striking appeal of her spoken English which received immediate attention. But her Hindustani, which she learnt almost immediately after her courtship with BK began in the library of the London School of Economics, was immaculate. It was just about as ‘high’ as it can get. And yet absolutely natural. Fori Nehru was an aristocrat, if ever there was one, of elegant speech.

So, noticing a certain slowness in my reply , she repeated the question in Hindustani “Tum kyalikhraheho?”

“Well,” I said, “since you ask…I am working on a book on the death penalty.”

“I see. Are you for it or against it?”

“Against.”

And then followed a typical Fori-ism. She did not ask the expected “Why should it be abolished? “ or “Will it be abolished?” but something altogether different. “Well, I am against it too. But tell me, if the death penalty goes, will something be lost in its abolition?”

I sat up on hearing that. Here was the Latin dictum audi alteram partem (hear the other party) being cited, and not by a barrister or a jurist but by a woman who for 66 of her 109 years was the classic ‘“spouse”, the housewife, the first lady and hostess beside Ambassador BK Nehru in Washington and London, Governor BK Nehru in Shillong, Srinagar and Gandhinagar.

Mrs BK Nehru, Shobha in her official description, Fori to most, survived her ICS officer-turned diplomat husband by 16 years. Fori Nehru not just saw but understood what she saw through a prism of her own unique mind. She understood — which is different from ‘accepted’, or ‘approved’ — her very important and not very simple family move from struggle to office, from imprisonings to power. She saw her husband’s official career weave its way through the transitions and tribulations of Partition, freedom, Gandhi’s assassination, with what can only be called a disinterested interest.

And she became for ‘ BK’ the rock of his life. Whether she agreed with him in all that he thought and did, and did not do, one will never quite know. I suspect she had her own very personal assessment of people and events, but if she did differ from him, she never allowed those differences to ever be known outside of her family. She was her husband’s alter ego, her legendary sallies at his expense only strengthening the impression. “Bijju and I do not sleep in the same room,” she announced at a large dinner party in Madras. And then to the relief of all around: “Because he snores.” If Fori was Bijju’s support, Bijju was Fori’s hero.

For me, BK Nehru was and remains an ideal: brilliant of mind, brave of heart, unsentimentally affectionate, the perfect administrator, diplomat, bearing a name that was as burdensome as it was strengthening. But I have, somewhat judgmentally, wished he had ‘stood up’ like his cousin Vijayalakshmi Pandit or his niece Nayantara Sahgal, against Indira Gandhi during Emergency, and later protested his transfer from Srinagar’s Raj Bhavan to that in Gandhinagar. And I have wondered: Could she not have put her foot down on those and similar occasions, telling to him: “Bijju, enough is enough. You are a Nehru. Do not allow anyone to push you around.” The answer is she could have. But, who knows, perhaps she did.

An unwritten autobiography has died with Fori Nehru. Populated by memories of noble acts by so-called small people, and the smallness, even meanness, of the powerful, it has taken away with it many private moments, some secret ones. But none in which this Hungarian-born student, who bowled over a dashing young Indian in the library of the LSE, London, betrays any regret at her choice of India, Fori’s India.

The writer is former Governor of West Bengal