Vandana Shukla

You don’t need a Gordon Geeko to inform: “Greed, for lack of a better word, is good”. The world we inhabit goads us to consume more. Bigger is better and more is less; the billboards, TV ads and shopping malls shriek, making one feel insignificant till one earns more to spend more. But there are mutineers, who rebel against the diktat of consumerism, the ones whose shopping cart is filled with ideals, not commodities. These warriors counter the economic terrorism with their armour of empathy and compassion. Collective good is better than individual growth to these followers of the inner voice. In their new world order — less is more.

Mala (name changed) spent the winter months of 2014 in Leh, as a volunteer at Mahabodhi International Meditation Centre, teaching the resident nuns English and maths. There was no compulsion for her to live in Leh, in sub-zero temperatures. She worked on Braille, to help the visually challenged get more reading material and established a maths lab for the students of Mahabodhi Residential School. The lab hundreds of students who come from the poorest families of the region that remain inaccessible for most part of the year. She worked through winters when the local students and staff, were away on vacation.

Had it not been for someone who knows her closely, one would never have come to know that she comes from an affluent background. To enter her home in Delhi one needs to clear a few levels of security . In Leh, she lived on a bare minimum and works for 10-12 hours a day; not to make money or a career. She is driven by love that does not seek reciprocation. “In summers I worked with an NGO in Delhi, it used to be so hot I would pour water on my clothes to keep cool. This time, I wanted to stretch my limits — physical, mental and emotional — by spending the winter in Leh,” she says. In her spiritual quest, ‘spiritual’ does not lead to an abstract quest for God, it is an endeavour to relate to humanity at a deeper level where the evolution of the self translates into betterment of the fellow beings. The world she has opted to work for — after earning a degree from one of the Ivy League universities — is not competitive. It grows with sharing.

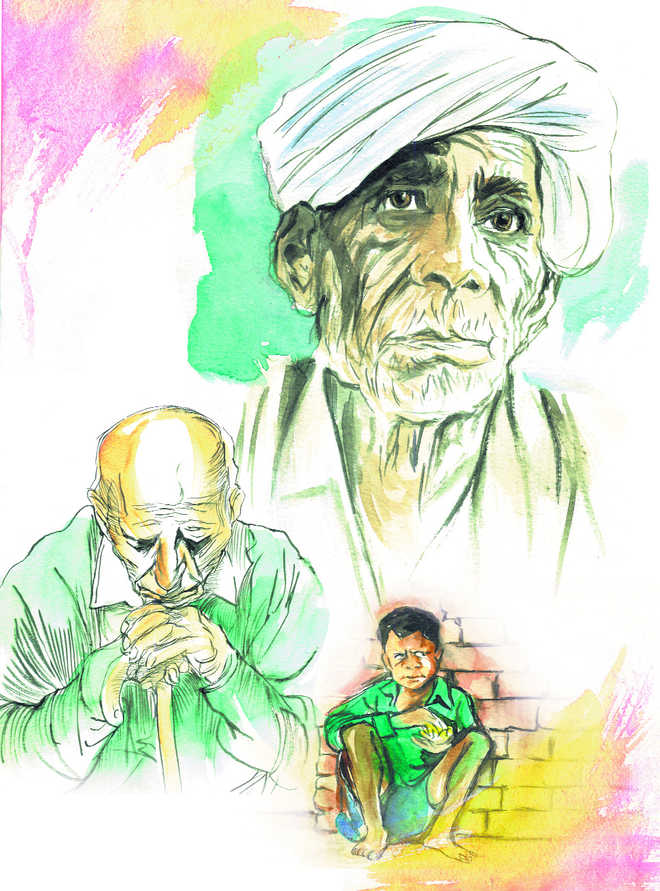

Adopting poverty or working with poor is not an act of romance for a few young and materially privileged men and women, there is more to it. This, in a way, is an attempt on their part to come to terms with the soul-crushing poverty around, which most of us walk past with insouciance.

Narayanan Krishnan was a bright, young, award-winning chef with a five-star hotel group. He was short-listed for an elite job in Switzerland in 2002. But a quick family visit to Manglore, his hometown, to visit a temple before leaving for Switzerland changed it all. It was a moment of self-discovery/ empathy/ compassion — he is not sure what he felt when he saw an old man eating his own human waste, under a bridge. “It shook me to my nerve on witnessing the power of human hunger. A spark triggered within me, I went to a nearby hotel and asked what was available; they had only idlis. I took the idlis to the old man. I had never seen a human being eat so hungrily. It made me cry. Like any other youth I had a great desire to work overseas, but this incident changed my destiny. I decided to feed the hungry than cooking for the already over-fed people. Feeding people who don’t really care what they eat seemed futile,” says Krishnan. He has been feeding more than 450 mentally ill and uncared, poor people, three meals a day ever since that encounter with the hungry, old man, since the last 14 years. Krishnan’s parents are middle-class government employees. After the initial shock, they welcomed his decision seeing his perseverance and determination. Letting go of their dream of seeing him “well- settled” was not easy though. Their son’s endeavour was a spontaneous reaction to heart-breaking poverty that exists amid affluence in our society. They developed trust in his mission and they themselves started feeding the poor on the streets. With little savings and support from his family, what began as feeding the poor programme took the shape of Akshaya Trust Organisation in 2003.

His story caught people’s imagination and help poured in. Social media also helped. “I strongly believe that no good cause will ever stop for want of resources, if a good cause has to stop for want of resources, the cause is not good enough,” believes Krishnan.

Eventually, Akshaya Trust built a home for the mentally disabled persons who are discarded by family. But the reputation of Akshaya took a plunge in 2013, when a 23- year- old mentally challenged woman ran away from Akshaya, blaming rape. Often, suspicion lurks about the intent behind selfless deeds in a culture that glorifies material growth. Krishnan says he took it in his stride, “To my understanding, any good deed in this country will be taken for a task. I took it as a test for me and my team. We were able to cross the fire because our records were clean. Though, it was painful to be blamed with such unworthy charges, my belief in the goodness of the people remains unshaken, else, how could we run this charitable mission. I believe 75 per cent of human beings remain unaffected by false allegations and propaganda, they are good and look at the positive side of things” he states with calm. A Malayalam film Ustad Hotel was made based on his life and CNN selected him for Top 10 Heroes of 2010 Award.

Tushar Vashisht, son of a senior police officer in Haryana, studied at the University of Pennsylvania and worked for three years as an investment banker in the US and Singapore. He, along with Matthew Cherian (Matt), had joined the UID Project in Bengaluru. Working for UID brought them in close proximity — for the first time in their lives — with the common man. And they began to wonder, how does a common man survive in India, on such low earning? They shared their maid’s flat, and calculated, excluding rent, they need to live on Rs 100 a day to be a common man. But it still did not make them poor, only average. Seventy-five per cent Indians live on less than this. Since the Planning Commission had defined Rs 32 as poverty line, they wanted to manage their life on Rs 32 per day.

The harrowing experience of living the life of poverty changed Tushar. “Hunger is a curse that makes you desperate and angry. We couldn't eat much of protein as it was expensive. Too much of carbs don’t allow muscle development and also give hunger highs and lows. Much of our time was spent planning and arranging food. We improvised by using peanuts, jaggery and bananas. The fact that PDS system subsidises only carbs — wheat, rice, sugar — made things more complicated. And we realised it’s a five-km circle of life. An average Indian can't travel much for work or opportunities, which explains slums in cities.”

He also became aware of a new kind of economic terrorism: things are more expensive for the poor. Essentials like vegetables are cheaper in large grocery stores that maybe far away for the poor, due to lack of refrigerator and transport, common man is forced to pay premium to local store for multiple purchases. “Even though most common men have mobile phones, they lack enough data to access information. If only we could subsidise that, it could lead to a mobile revolution in the country,” he adds.

Living the life of the poor, even for 100 days, did it in some way cleanse the guilt one carries for living a privileged life? There are no conclusive answers, says Tushar. “Initially, it was difficult to re-adjust to the privileges we enjoy. And the feeling of guilt was there. However, later on, I went through a normalisation process to feel greater empathy towards people on the street and in the villages. I feel like I understand my countrymen better and have learnt to be grateful for what I have. It has also reduced conspicuous spending for me.”

But the real privilege came with the learning that, “There is greater compassion and trust at the bottom of the pyramid. There, people support each other. We were not one of them, yet the way they shared their limited resources with us and helped us survive was an eye opener.”

Tushar is now co-founder and CEO of a startup called HealthifyMe, which is helping more than two lakh Indians get healthier and better life. Change, as understood by the educated middle classes, is aspired only for higher positions and better material comforts. Few though, take to a road leading down to expand the lexicon for true modernity.