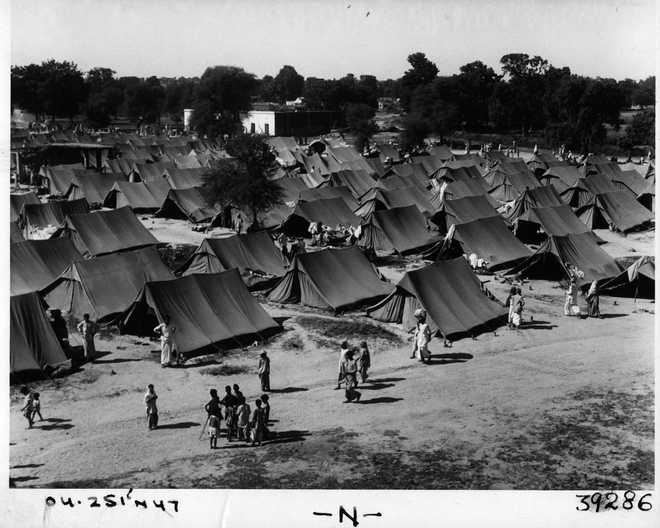

A view of one of the innumerable camps set up to manage the influx of refugees during the Partition. photo courtesy: Partition Museum, amritsar

Sarika Sharma

On August 16, 1947, my great grandmother stood on the platform of Old Delhi Railway Station to take the train back home to the North-West Frontier Province. Along with her stood five young children; her body covered in a shawl and a small bag in her hands,” recalls Aanchal Malhotra. In that bag was also a maang tikka she had brought along from the North West Frontier Province. Aanchal’s great grandmother never made the journey back and her maang tikka was to survive the test of time, circumstances and geography on this side of the border. Both as a researcher and as a great-grandchild, this piece of jewellery is what makes for an important part of personal and shared history for Aanchal. Something that connects her to not just her own great grandmother, but to what she left behind on the other side of the border. As she realised this, Aanchal began collecting all such articles that made the arduous journey from Pakistan to India. And hers is not the only effort to protect the memories.

Time is slipping away fast. Memories of the Partition are still a tangible reality. Tomorrow, these might be, well, just memories. Thankfully, as one generation passes on, another is waking up to this reality, recognising the need for documentation to save these for posterity before it is too late.

Long before Aanchal took the plunge and came up with her thesis, Remnants of a Separation, during her Master in Fine Arts at the Concordia University in Canada, US-based Guneeta Singh Bhalla had begun recording the testimonies of the Partition’s survivors and sharing these with the world online. Guneeta grew up listening to stories of the great divide from her grandparents. She knew it was a traumatic event, but never learned about it in high school in the US. Her friends reasoned it was probably not a big deal. But her experiences said otherwise.

“The thought that we could let such a massive historical event slip through the cracks, without documenting it at the level that it should have been, deeply troubled me. I feared we were going to live in a world where history would keep repeating itself.” By then, she had also realised that first-hand accounts validated the experience of the Partition, “made it human, palatable and accessible”. That is what she then set out to do: Document people’s accounts of the Partition. “Only those with lived experiences could truly attempt to convey the horrors and trauma of that time. A trauma that affected millions upon millions of people — a population larger than many Western European nations combined!” The 1947 Partition Archive was finally born when she visited the Hiroshima Peace Memorial in 2008. “When I came across the witness archives in Hiroshima, that’s when it clicked. It was so powerful to hear survivors’ stories of experiencing the atomic bomb. I knew the same had to be done for the Partition.”

Guneeta began as a solo story recorder in 2009. The 1947 Partition Archive was formally founded in 2011. Today, they have recorded more than 3,000 stories. “More than 25 story scholars and oral history apprentices and hundreds of volunteer citizen historians from around the world record stories today. The stories have come in from more than 300 cities and villages around the world and 12 countries. Most stories are from India and Pakistan,” says Guneeta, who is based in Berkeley. As she looks forward to the project’s official launch in India this September, she says they are partnering with a number of top universities to host local centres where the stories will be accessible to local populations. Also in the pipeline is a centre for learning, which will be a permanent exhibit and memorial on the people’s history of the Partition.

In India, Aman Jaspal tries to house this history in a restaurant aptly named Sarhad, for, it is situated a kilometre away from the Wagah border. However, it was born out of disdain for all that conspires at the border and all that ceremonious display of nationalism. “Our shared history is so different from the jingoistic nationalism at play there.”

“Sarhad is a celebration of the architectural, cultural and culinary heritage of pre-Partition Punjab in general and Amritsar-Lahore in particular,” says Aman.

So, what is it that makes it important for the memories to be nurtured and kept safe? For Guneeta, it is important that we listen to stories of the Partition. “Without the human stories of the Partition, our understanding will always be limited,” she reasons. For her, reconciling with the past is important for a safe and better future. “I feared we would have to live in a world where history would keep repeating itself. In the early 2000s, for example, I saw the same chaos unfold in Iraq. An entire system of governance was replaced very quickly. In my mind, knowing what I did about the Partition, the events I was seeing on television were predictable.”

However, the hunger to listen to stories must be preceded by the urge to share. The heart to shed inhibitions and tell it like it is — whether good, bad or ugly. That is precisely why Subodh Mathur, who runs the portal, India of the Past, insists on recording experiences as lived. “No analysis, no commentary — just stories about people’s experiences,” he says, as he excludes the editor from the scene and lets the narrator and the listener come face to face with raw memories. The portal has many stories from Punjab and Bengal.

However, recording stories of the Partition is not easy. Memories are sheathed in time. These can be easily broached upon, but those who have lived them are not going to let them out so easily. Tucked away in some dark corner of the heart, those memories were only meant to be lived through long nights, quickly wrapped as twilight began to descend.

That is why it has often taken Aanchal hours to convince people to talk. “People don’t divulge these memories easily. But once they begin, it is difficult to contain memories,” she says and adds it is odd how material memory is an effective yet highly underrated realm in the Partition studies. “It offers incredible insight into the tangible material culture and society of the time. What people carried/ could carry determines a lot of the circumstances in which they left their homes and what kind of social structure they would have come from. Did they know about the Partition? Did they have the time to pack? If they did, what did they bring along... You ask yourself this now — if you had to leave your home at this moment, at this instance, what would you take with you?” she asks, leaving you looking for answers.

Moving on from the tragedy

Prof Ian Talbot from the University of Southampton, the UK, says that although there now are more attempts to document testimonies, the efforts are few when compared with the Holocaust. Talbot, who has co-authored a major study on the Partition of India and its aftermath for the Cambridge University Press series New Approaches to Asian History, says, “Most of the work is down to individual researchers and academics as governments have stood clear of what is a sensitive issue, both in terms of cross-border relations and internal social cohesion.” One way around this would be to move from a victim discourse, to a narrative of the contribution of migrants to the early processes of nation formation and state construction. He says a genuine understanding of the past, rather than in a politicised form, is vitally important for future development. “It would help healing processes that are still required and would also reveal a growing sense of national maturity.”

…so that history doesn’t repeat itself

Lady Kishwar Desai, chair of The Arts and Cultural Heritage Trust, is setting up a museum dedicated to the Partition of India in Amritsar. She feels it is important for people to remember the Partition for the sheer enormity of the event. “They say it left 14 million people dead, but we are now getting to know that the numbers might be more. Many more died at refugee camps and in riots. We can’t just let their sacrifices for our independence go waste,” she says. The museum would house testimonies, documents and memorabilia related to the Partition. And she says at their recent exhibition in Delhi, they had people coming and crying for their parents. “They were overwhelmed that, at last, they were being remembered. It is tragic that we have let a huge part of the generation pass on. But we must value whatever is left so that history doesn’t repeat itself,” Desai says. — Kishwar Desai