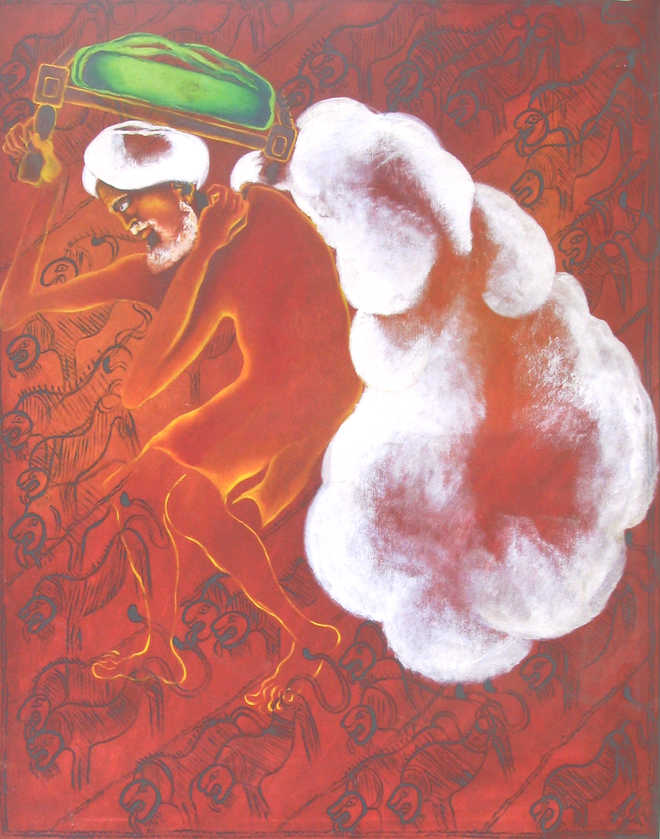

Those who made the journey: Arpana Caur’s work on Partition shows her grandfather carrying Guru Granth Sahib on his head and a bag of memories across his shoulder. The work has been reproduced with permission from the artist

Sarika Sharma

Partition haunts me every day. Yes, it still does,” says Balbir Momi. Seventy years is a long time, a very long time, but the memories of those days still play out before his eyes. Almost like a film... Of leaving home on a bullock cart... the cart getting stuck in mud, the fear setting in. The Sacha Sauda camp 12 miles away from his home at Nawan Pind in Sheikhupura district. The mindless firing by Pakistan Baloch military from running trains, the killing of around 1,300 persons right before his eyes...

He still remembers the 16-hour journey that brought him and his family to Kasoor. When it ended, Momi realised that the nightmare had just begun. “There was no food, no water. People were dying of malaria and diarrhoea. Next day, we took a train to Ferozepur Cantonment, reached Bathinda somehow and entered the burnt house of a Muslim family that had seemingly migrated to Pakistan,” Momi, now 80, writes to us, the email ending abruptly, with the words: “Will continue”.

A day later, he writes back again. This time, it is about joining the pieces. Now settled in Brampton, Canada, Momi tells us that he has visited Pakistan several times in the past few years and made a lot of new memories. He has been writing on Partition and in Shahmukhi, the language he first learnt, a language from the land he first learned to love.

Lakhi Kishinchand Shamdasani was 13 years old in 1947 and was observing how everyone in his family circle was confused. There were rumours that everyone would leave the place and then return back to their homeland. The day of that journey arrived. “We left the city with our belongings one afternoon and locked ourselves inside a train wagon. We didn’t open its door for a day and a half because of the fear of looting.” They stayed in Abu Road, Rajasthan, for over a year and then moved to Pune. Thankfully for him, he could put the past behind rather easily. “I soon got used to the different places where I settled and in 1967, I moved to Spain.”

The great divide forced thousands to flee home, only in the hope of returning later. But there was to be no return. It was wilderness-like out there. Violent elements, emboldened by lack of law and order, unleashed arson and loot both on properties and people.

“The memories of Partition, you ask...” begins Dr Khalida Ghousia Akhtar, who is settled in Walnut Creek, California. “It is the Holocaust of the East, not mentioned in books.” Dr Akhtar was based in Banihaal town at the foothills of Pir Panjal in Jammu. “I was not even 10 when we had to run for life from place to place due to a group that wanted us killed because we were related to Chaudhary Ghulam Abbass, a Kashmiri leader who opted to side with Pakistan. We ran for our lives across the border, the distance of four miles to be covered in less than one hour. I was carrying my six-month-old sister; my mother carried my brother, who was around two. Running beside me was my aunt Olga Zubair; she was seven months pregnant.”

They settled in Sialkot and moved into two vacant houses of people who left for India. “These houses, just like ours, had been left in a hurry. Life was uprooted on both sides of the border. Two nations were erected on foundations soaked in human blood,” she broods. The family eventually settled in Sargodha, Pakistan, where they were given a villa in exchange for lost property. Dr Akhtar went on to complete medical school, with an emphasis on gynaecology and surgery. Today, she calls Partition a great teacher, a great mentor.

Shruti Devgan’s grandmother or dadi, called beeji by the household, was luckier. She didn’t have to leave home. Instead, she gave refuge to many of her relatives at her home in Sarhali near Amritsar. A visiting professor in sociology at Bowdoin College in Maine, US, Devgan grew up listening to stories that began with ‘Jadon raula paya’. The most painful of these stories was a particular graphic description of how trains adorned with “garlands made of mutilated women’s breasts” arrived on train stations. “It felt unreal. I remember listening to the tales horrified and trying to imagine it, but not quite able to do so,” she recalls.

Later, as a student of Trauma, Memory, Identity in a US college, Devgan planned to study both the Partition of 1947 and the anti-Sikh violence of 1984, and ended up focusing on the latter. “As a scholar, I think of the ways in which the events around Partition acquire narrative form. Even the account I’ve shared with you is a memory of a memory. I make sense of the events of Partition and how they impact me in the very act of sharing these stories with you. When I look back and think of what my near and distant family members suffered, I think of the ways in which the story of nation-states is also the story of my family, and consequently, of me,” she says.

Hard as we try, memories don’t let go of our being. But what happens when layers of years are added to them? We ask Anindya Raychaudhuri, a lecturer in English at University of St Andrews, the UK, whose work revolves around postcolonial and diasporic identities and cultures. He feels the memories have since been layered over with memories of life in the West, and the struggles involved.

“The generation that arrived in Britain immediately after Partition might have come to Britain all angry and bitter, but when they got here, they discovered that when faced with racism in Britain — they were treated exactly the same whether they were Indian or Pakistani. They discovered that they had to, to some extent, put their differences aside and fight together to create a home for themselves in Britain.”

This is neither to say that the differences disappeared, nor to say that enmity and anger does not exist in Britain. He says it is more complicated by the added factor of emigration. “People were forced to leave their home once during Partition, and then again when they moved to Britain. They, then, remember this as a double loss of home.”

Anindya has seen people break down and cry just at the thought of being able to go and visit the home they had to abandon. The home they left to return later, not knowing there would be no return. Dr Akhtar and her family too believed they would go back home one day. But more than that, what haunted her for decades were the scenes of lamentations, loud cries and women beating their bosoms. “A flashback is still shocking, very painful and torturous to recall. They made me too sensitive to enjoy my life. I am unable to laugh full-heartedly. I am a victim of my trauma and of that faced by those around me,” she says.

Still shying away

Shauna Singh Baldwin, Canada-based author of Partition tome What the Body Remembers, feels the discourse around Partition is still highly Commonwealth-centric. “We have so little understanding of the post-colonial impact of Partition on a world level. Certainly, we have not learned much from this cataclysm on a global basis since we're discussing another partition, this time of Israel/Palestine as some kind of solution to their postcolonial mess.” Baldwin feels British historians and educators are far behind where it comes to acknowledging British responsibility for the deaths and displacement of Partition. Also, she feels her generation only knows the costs of Partition. “For us in the diaspora, the legacy of Partition lies in the senseless borders of distrust between Indian-origin and Pakistani-origin people; between Bangladeshis and Pakistanis as well. Borders are not only on maps... they have been created in our minds. We have to overcome Partition’s borders of the mind to address the many challenges we face as desis.”

Anindya Raychaudhuri, who teaches at University of St Andrews in the UK, feels the problem is that children, whether in the Subcontinent or outside, grow up distanced from 1947. “It is not much talked about within the family, or in public. People grow up with rumours and half-truths. Partition is does taught in schools in both the Subcontinent and Britain, which does not help. There are notions of shame within families in both the places, which prevent discussions. Often, the stories are just too painful to share.”