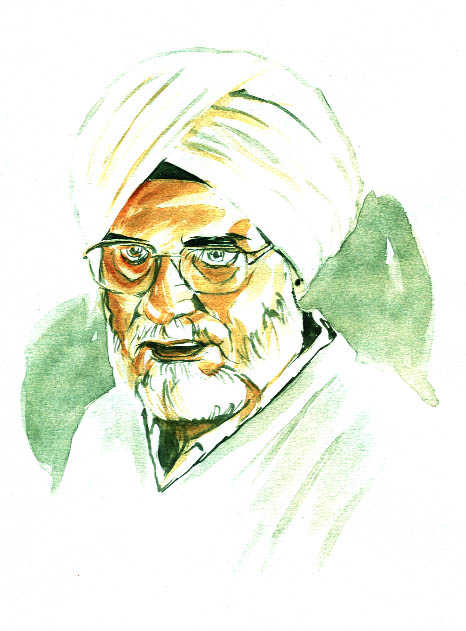

Illustration: Sandeep Joshi

Sarbjit Dhaliwal

WHILE returning the 2006 Sahitya Akademi Award a few days back over the “growing intolerance” in the country, Prof Ajmer Aulakh acknowledged that it was not necessary to mark protest by returning awards. “People can protest in other ways also. But I had this award and chose to return it to join the protest.” This impulse to speak out, to stand up against what he considers wrong, and fight for rights has always defined the Punjabi playwright.

Prof Ajmer Aulakh has, through his scripts and stage performances, inspired the marginalised peasantry and working class to fight the “exploitative” system in whatever form it exists. Using minimal stagecraft and the emphatic Malwai dialect, he has played a pivotal role in popularising theatre in the countryside. Few have been able to match his skills in depicting the reality of rural life, with all its contradictions and distressing strains, making him one of the most popular dramatists in the Punjabi literary firmament.

He was recently nominated by the Punjab Languages Department for the Punjabi Sahit Rattan Award 2013 for his contribution to literature.

The rural setting of his plays and the artistes — mostly from rural background — are the strength of his stage performances. His entire family, including his wife, three daughters and sons-in-law, is part of his plays, which attack various organs of the system, taking these to task for the oppression and extreme poverty of small and marginal farmers.

The soft-spoken Aulakh has, for decades, also shaped the future of many a student. I too had the privilege to learn from him at Nehru Memorial Postgraduate College, Mansa, where he taught Punjabi for 35 years. He pens plays that are loaded with wit, satire and a message; always a message.

“I used to write poems and stories in Punjabi when I was in school, but had no inkling I would be a dramatist someday,” says Aulakh. “I even wrote a novel Jagirdari against the feudal system after my matriculation examination.” A transformative moment was college principal BP Mohan giving him charge of cultural activities. Aulakh would help students prepare one-act plays for inter-college competitions. He started with skits and action songs in 1970. His first one-act play Shaitan Da Astifa was based on Krishan Chander’s popular story in Urdu. It won the second prize at the PAU festival.

Two years later, he wrote his own one-act play Zindgi and Insaaf, depicting Baba Banda Bahadur’s life. In 1973, he authored Edra-Kadibra, which was later renamed Arbad-Narbad Dhandukara. While Bagane Bohr Di Chhan established him as a frontline dramatist, Behk-da-Roh made him a topnotch playwright and director. With a dozen books to his credit, Aulakh’s other successful plays include Anne Nishanchi, Ik Hore Ramayan and Bajian Bahan.

But it wasn’t always easy for him. Born in a marginal farmer’s house at Kubedwal village near Barnala in 1942, Aulakh’s family shifted to Kishangarh Farwahi village (near Mansa) in 1944. He grew up in the shadow of the Muzara (tenant) movement in the 1940s against biswedars (feudal landlords), who had usurped vast chunks of land. The majority of farmers, including Aulakh’s family, used to cultivate the land as tenants with no ownership rights. Farwahi emerged as one of the centres of the anti-landlord movement, which in 1952 succeeded in getting ownership of land for tenants in the Patiala princely state, which became a part of PEPSU.

Three events impacted Aulakh’s life and pushed him towards revolutionary writing. First was the humiliation his mother was subjected to by a landlord’s agent in the village, all over a corncob. “My mother was insulted because of me. I wanted to eat roasted corn, so she took one from the fields for me,” says Aulakh.

The other incident occurred when he was still in school. Along with Hakam Singh Samaon, who later joined Maoist ranks, Aulakh studied at National High School, Bhikhi. The Headmaster refused to send his fee to appear in the matriculation exam, for he thought Aulakh would never clear it. Hakam’s father, an influential man, made the Headmaster send his form and Aulakh passed in first division. “I was the first to secure first division in my village and it made me a celebrity. But the attitude towards rural students hurt.”

It was during this time that he developed a liking for a girl who would call him “pagal”. He tagged this epithet till his graduation. And so, he became Ajmer Singh Pagal.

The other episode that pained Aulakh took place at Khalsa College, Amritsar, where he took admission in non-medical on the assurance that he would be shifted to BSc (Agriculture) whenever a seat fell vacant. However, a boy with less marks got the seat. Aulakh wrote a stinging letter to the principal, following which his name was struck off the rolls.

Dejected, Aulakh pursued his graduation privately (popularly known as “via Bathinda”). In 1963, he took admission in MA (Punjabi) at Punjabi University, Patiala, and after passing out, got the job of a lecturer at Nehru Memorial College, Mansa.

Aulakh was influenced by the Naxal movement, but never became an active member. And so, his works show strains of Marxism. With a view to muzzle ‘dissent’, a case was registered against him during the Emergency for conspiring against the State. He was later acquitted.

Every penny counted, with his family facing financial constraints. He began to take tuitions at a private academy. “A sum of Rs 15 was paid to me. Once, I got only Rs 14. I was disappointed. Even this small amount of Re 1 meant a lot to me.” Like it does to those who flock to see his plays, eager for a message of hope and change.