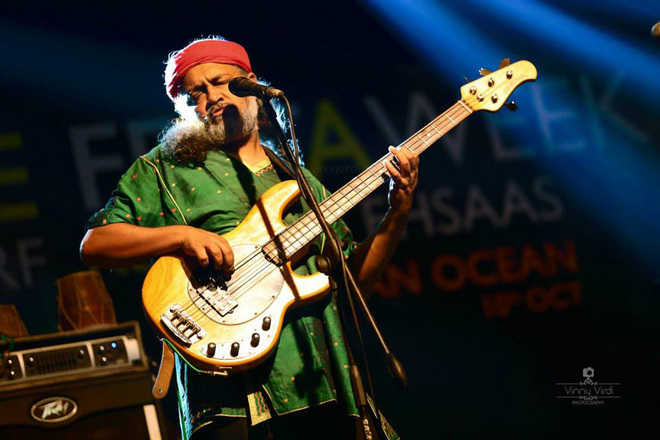

Being political: Indian Ocean’s Rahul Ram used political commentary and comedy in “Aisi Taisi Democracy”

Samar

“Ye line mein khada hai tu jo aaj kal

Kya sochta hai desh jayega badal”

Addressing the social climate in the aftermath of demonetisation, a song featuring these lines became quite popular. Set to the notes of “Jeena Issi Ka Naam Hai”, it captured the public chaos much better than many articles penned on the subject at the time. Due to the freedom and directness of the format, it managed to bypass a lot of clutter and get to the heart of the matter. It was a fresh, creative approach during the upheaval and represents a growing trend.

In India, this socio-political breed of music is, of course, not new and dates back to at least the earliest musical renditions of Kabir’s verses. Still, this culture, in its newer shapes, is more vibrant than ever today. There are a variety of artistes across genres that are making their voices heard and are increasingly audible to a large number of people. This is largely thanks to the many uploading and sharing platforms on the internet.

Battling injustice

Whatever occurs in society eventually winds up as rhythm, beats and melody. Politics is no exception; in India, it creates a new sub-genre of music, tailored to the unique issues plaguing the nation, and finds life in numerous languages and styles.

There is much variation. Poet-activists and singers like Gaddar and Kovan have long addressed entrenched discrimination in India. Artistically, that is a far cry from a band like Indian Ocean, which has made use of revolutionary poet Gorakh Pandey’s words. Troupes such as the Kabir Kala Manch are singularly political and have long been dedicated to battling social injustice.

Singer-activist Bant Singh’s work is in the same vein. Hailing from Mansa, Punjab, he has championed the causes of labour rights and Dalit empowerment. However, his activism has come at a price and his physicality is a testament to social injustice he has personally suffered.

In 2002, his daughter Baljit was gangraped by some upper caste men in their village of Burj Jhabbar. In a rare decision for Dalits in such positions in rural India, and despite social pressure to back down, Bant Singh decided to take the attackers to court. Not only that, he managed to win his case. Then, in 2006, he was attacked by a group of upper caste boys in an act of brutality that saw both his arms and a leg amputated.

Remarkably, this did not crush Bant Singh’s spirit. He sings of agricultural oppression and revolutionary ideals in a continuing activism, which is pushing beyond his native Punjab. If anything, the courageous story has sharpened the spotlight on the words of the ‘singing torso.’

Also from Punjab, the teenaged Ginni Mahi has made quite a dent as a musical crusader against caste. Her songs are about Babasaheb Ambedkar, Sant Ravidass and the Jatav community to which she belongs. As a young woman addressing a serious social ill, she has drawn much attention to herself (and her cause) with songs like “Danger Chamar” and “Fan Baba Sahib Ki”.

In the recent times, acts which utilise both political commentary and comedy have also come to the fore. “Aisi Taisi Democracy” is an example (and features Indian Ocean’s Rahul Ram). And, in an altogether different sphere, electronic music has also entered the fray; Dub Sharma’s “Azadi”, which mixes a popular civil rights slogan with a revolutionary Punjabi refrain, has seen reasonable interest on the internet.

Sheetal Sathe, former singer with Kabir Kala Manch, believes musicians have a responsibility towards society.

“Kabir Kala Manch started out in 2002 after the Gujarat pogrom. I joined in 2004… Since I have been singing, I have felt ours is a caste-based society. Artistes have an important role in the fight against brahmanical structures and make people genuinely let go of caste considerations,” says Sathe.

Asked if forms of music which are relatively newer to the country can be used in such pursuits, she concurs. “There no such barricades. Other styles can be used for such causes… Caste forces have been at play since before any particular government. Social revolutionaries in different eras have fought against inequalities in their own ways.”

Song of protest

Across cultures and eras, artistes have explored socio-political questions. Through genres ranging from folk to metal, these phenomena have been addressed by both haves and have-nots. There is, of course, music which can be deemed pro-establishment, such as the national anthem. There is also promotional and propaganda music, which may be religious or political or both. Examples of this can vary from Soviet-era Red Army anthems to Aam Aadmi Party’s Punjab election campaign song, “Jhaduwala”.

Where political music truly finds its essence, however, is in the spirit of resistance. Whether it is the birth of the blues on cotton fields in the American south or the audacity of Russia’s feminist punk outfit Pussy Riot, it is the act of going against the grain.

This has been seen all over the world. During the 1960s, which contained both the US Civil Rights Movement and Vietnam War disillusionment, Bob Dylan took the value of protest music to new heights. Songs like “Masters of War”, “Blowin’ in the Wind” and “Times Are A-Changin’” resonated with young people so deeply that they became essential parts of modern political protest.

They pushed dissent into the mainstream; a feat repeated later in the US by acts like “Rage Against the Machine” and “System of a Down”. In China, Nothing to My Name, a Mandarin rock song, became a rallying cry for activists during 1989’s Tiananmen Square agitation. To our immediate west, Pakistani bands like Laal and Beygairat Brigade create music to foster social consciousness and speak truth to power.

The examples are endless. Why such music is essential is for its flexibility. It can be accessed by all. For those who cannot read, or mistrust mainstream media, it can provide alternate avenues of understanding. It gives parallel expression to ground realities that political and journalistic rigidities often don’t accommodate. And, it has more freedom with words.

In the age of internet

A quote by Bertolt Brecht goes: “Art is not a mirror held up to reality but a hammer with which to shape it.”

The Indian artistic landscape is fertile with this sentiment, even if oppression remains the more visible currency and the art often finds itself silenced or defeated.

Today, though, it has a better reach than ever; an expanding internet and social media are changing things. As more and more artistes embrace and learn to wield modern connectivity, the audience inevitably grows. It is now a simpler activity to be heard on a larger scale, thanks to the relatively democratic nature of the web.

YouTube, SoundCloud, OK Listen and a range of other websites make it possible for musicians to upload their content for anybody who is interested. Social media further enables their music to be shared with other interested listeners and spread word. There are uncharted possibilities in today’s age where voices are harder to quell and the grapevine is too complex to monitor.

It is not easy, though. Commercial music is one thing, but for art to go up against powerful interests which perpetuate commercial and social inequalities is quite another. Practitioners of protest music have to be driven by an ethical quotient, for, at least in India, it is not by-and-large a money-making end. There are more risks than perks.

Still, artistes take the mantle and find creative ways to frame their outrage. They are using modern means, taking injustice seriously and carrying ahead the legacy of Ritwik Ghatak’s assertion that ‘art means war’.