|

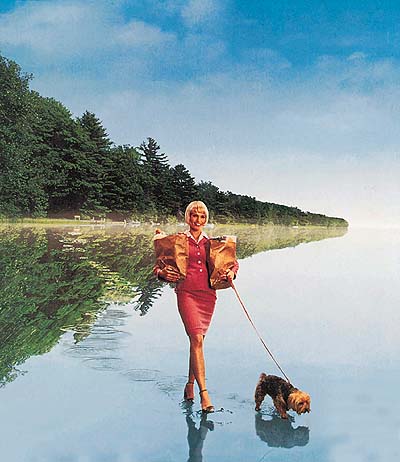

Want to walk

on water? No problem

By Roopinder

Singh

SOON your memories will be reduced

to a series of zeros and ones, and let alone having any

objection to it, you will actually encourage it, ask for

it. No, this is not a surrealistic vision of reality, but

a realistic assessment of what is happening around us.

Digital photography is moving at a steady clip away from

the esoteric confines of professionals to ordinary

people, even in India.

Most of the photographs

that we see printed have been digitised, as have most of

the big, attractive displays that dominate skyscapes in

metropolitan cities. A 12-foot-high and 30-foot-long

translite photograph of Takht Sri Kesgarh Sahib, taken by

a Chandigarh-based photographer, is on display at

Anandpur Sahib. It is said to be India’s largest

photographic image. This feat was achieved by using the

hybrid process combining the best of conventional

photography with digital processing. Soon, it seems the

trend will invade our homes and our family albums.

What exactly is digital

photography? Traditionally, the darkroom side of

photography has been associated with chemistry and

chemical processes (in so far as the making and

processing of photographs involving various chemical

processes is concerned). When you replace these with

electronic processing, you get digital photography.

"The biggest thing

in the past 10 years has been auto-focus, which is

increasingly being accepted by professionals as well.

Digital will be the most important development of the

coming 10 years," says Hoshang S. Billimoria, Acting

Editor, Better Photography magazine

To discuss digital

photography a bit more technically, you can acquire a

digital image, (which is a series of ones and zeros in

machine language) in either of two ways: either you take

a photograph with a digital camera, or you convert a

film-image to digital format using a scanner.

In digital cameras,

unlike conventional cameras, the image is recorded

through light-sensitive silicon picture elements, or

pixels, that convert it into electrical impulses, which

are recorded in the camera’s electronic memory. On a

film, the image is recorded through light-sensitive

silver-halide crystals, which are then developed

chemically. The image on film is in analog form — it

can’t be directly stored or manipulated in a

computer. Silicon chips, on the other hand, record the

image in digital form so that the image can be stored and

manipulated in a computer.

Naturally, the more the

pixels, the better the resolution, and the more the cost

of the camera. Megapixel cameras (which have at least

1000 pixels on the long side of the image) cost much more

than ordinary ones. The pixels are neatly laid out on a

charge-coupled device (CCD), which is an expensive

electronic gadget.

In general, we have to

remember that even this seemingly impressive figure of

megapixels does not compare with film, which has hundreds

of million crystals. The limited range and number of

pixels means that the digital image is only an

approximate representation of the subject.

Except for some

specialised, time-sensitive applications like

photojournalism, it is difficult to justify the cost of

such machines, typically around Rs 6 lakh or more.

"The best solution,

if you are computer crazy, is to take a photograph with a

film camera, use a digital scanner to digitise the

photograph, use computer software to manipulate it, and

print it any way you want to," says Billimoria.

For most of us, this

hybrid approach is the route to digital photography. You

combine conventional cameras with either film or print

scanner to digitise the images so that they can be

manipulated and optimised in the computer. The finished

files can be printed digitally on a colour printer or

sent out to be printed photographically. This way you do

not have to spend money on a digital camera and still get

the benefits of digitisation.

"In the Indian

context, photographers will not be comfortable shifting

to a brand new medium (digital). It is a smart move by

the manufacturers to strike a midway solution between the

print and digital media.

In traditional

photography you get what you see, if you record it

correctly; whereas in the digital side, there is more

scope for correction/manipulation. You can treat it as an

advantage as well as a disadvantage, you can have the

kind of images you require, though they may not be

‘true’ images," says Manas Dewan, a

photojournalist with Better Photography.

You may ask what is it

that digital imaging can do for you. Well, it can easily

take care of exposure problems (if the image is overall

too dark or bright); contrast issues (bright areas are

too bright as compared to the dark areas in the image, a

problem common in photographs taken with flash); overall

colour cast problems (your picture has a tinge of a

particular colour), or improve dull, lacklustre colour.

The key word here is

‘ease.’ These very problems can also be tackled

using the traditional chemical processes, but often the

time spent and the cost can be quite high. What neither

of these processes can do is turn you into a better

photographer, or fix blurry images caused by poor camera

focus or camera shake.

What has made digital

imaging very popular with people is the way in which

images can be manipulated in computers, using image

editing software like PhotoShop. It is this which makes

it very easy do image editing and remove blemishes in

photographs, adding things to them, combining them and,

at times, manipulating them in various ways.

It’s easy to fix

red-eye, to remove phone wires from house photos, and

even to put blue skies into the picture. "You can do

much more in digital photography than in traditional

photography. For example, if you retouch a traditional

black and white photograph, you are limited by the

original in the kind of colouring you can do, whereas in

digital photography, you can give realistic skin tones to

the photograph," says Parkash, a Bombay-based

digital photography specialist, who works for a company

which develops customised software for India.

"With our software,

you just pick up the skin tone from the many options we

have and paste it there. You can mix different types of

photographs and use any size of images, and you can use a

machine to go up to 50" width and any length in the

high end processing machines available in India. The

input, however, has to be very good. 12"x18"

prints on photo paper," he adds.

At the PhotoAsia

exhibition, which was held in Delhi recently, there were

many vendors exhibiting wares combining digital and

traditional photography. Among the interesting things on

display was a software programme that enables a person to

colour a black and white photo, manipulate it and even

combine more than one photo. This is said to be quite

popular in small towns.

This kind of software,

which does not require much technical knowledge, is what

is required for low-end use of small studios. Often

people have faded or even torn black and white

photographs of their elders. These can be converted into

fairly realistic coloured images and a print given

without too much cost (between Rs 300 and Rs 500),

according to one vendor.

Once the changes have

been made in image editing software, the next step is

storing the photographs. This is most often done on the

hard disk drive of a computer, though some people may

require portable media for taking such files to other

locations.

Often the images form

very large files and compression software is used to make

the files small. A programme that applies a set of

complex calculations (called algorithms by the

technicians) performs compression to a file to make it

smaller. The compression program basically squashes the

information in a file so that it can be stored in a

smaller space, and can later be de-compressed back to its

original size. Of course, if a picture-file is compressed

too much, you cannot re-create exactly the same scene

with the same image quality as in the original. It is

generally believed that a compression ratio of more than

10:1 causes loss of image quality. JPEGs (pronounced

JAY-pegs) and GIFs and TIFFs (both rhyme with

"stiffs") are common programmes (algorithms)

that can be used to save the image and, possibly, provide

compression.

A transition from the

digital mode to the physical one (your picture looks good

on the computer but you want to have it in your hands) is

the last step. For this, the photos can be printed out on

inkjet printers, which give quite a good resolution,

specially when it is printed on special paper that is

meant for photographs.

At the higher end are

the continuous tone printers, which give a better result,

at a much higher cost.

Of course, for the

really demanding customers, there are the digital laser

writers. With such machines, it is now possible to

"write" continuous tone, true photographic

quality digital images on films, negatives or slides,

which can then be enlarged on conventional

enlargers/printers, to produce brilliant colour pictures,

prints or transparency materials. In other words, you get

the best of both the worlds, the clarity of conventional

photography and the image-enhancement capabilities of

digital photography. Such a marriage of the two

technologies is what most professionals are placing their

bet on.

Photography has a long

way to go as far as growth in our country is concerned.

"Over the years in India, the industry has been

stifled because of inordinately high duties, with the

result that the entire trade was under the carpet, in the

grey market. The potential, however, is huge," says

Billimoria. He quotes some statistics: "In India,

only 21 per cent of the urban households have one camera

per household, the figure drops down to 4 per cent in

rural areas. In Japan, it is 250 per cent. That means

that in a household of four people, they would have 2.5

cameras. This shows how much more we have to travel. We

consume about 75 million rolls of film; Japan, which is a

tiny country, consumes 400 million rolls. Then, the only

way we can go is up."

Now that we have

discussed digital photography, you may ask: What is the

future of conventional photography?

Think of digital

photography and conventional film-and-chemicals

photography as parallel technologies rather than as

"one-lives, the-other-dies" competing

technologies. Digital does certain things better and some

not as well. The point to note is that photo manipulation

is now within the grasp (and pocket) of mainstream

consumers. As far as the eventual prognosis is concerned,

we can consider the fact that personal computer servers

took years to supplant proprietary minicomputers. PCs

used as word processors took years to usurp dedicated

word processors. Desktop publishing took years to

decimate traditional typesetting. Desktop photography,

too, is expected to take a long time to displace

traditional photo processing systems. Happy clicking.

Digital definitions

Algorithm:

A detailed sequence of actions to perform to

accomplish some task. Named

after an Iranian

mathematician, Al-Khawarizmi.

Bit:

Binary digit. The unit of information; the amount

of information obtained by asking a yes-or-no

question; a computational quantity that can take

on one of two values, such as true and false or 0

and 1; the smallest unit of storage - sufficient

to hold one bit.

CMYK:

Cyan, magenta, yellow, and key. A system for

describing colours by giving the quantity of each

secondary colour (cyan, magenta, and yellow),

along with the "key" (black). The CMYK

system is used for printing. For mixing of

pigments, it is better to use the secondary

colours, since they mix subtractively instead of

additively. The secondary colours of light are

cyan, magenta and yellow, which correspond to the

primary colours of pigment (blue, red and

yellow). In addition, although black could be

obtained by mixing these three in equal

proportions, in four-colour printing it always

has its own ink. This gives the CMYK model. The K

stands for "Key’ or ‘blacK,’

so as not to cause confusion with the B in RGB.

GIF:

Graphics Interchange Format. A standard for

digitised images compressed with the LZW

algorithm, defined in 1987 by CompuServe (CIS).

Grey-scale:

1. Composed of (discrete) shades of grey. If the

pixels of a grey-scale image have N bits, they

may take value from zero, representing black up

to 2^N-1, representing white with intermediate

values representing increasingly light shades of

grey. If N=1 the image is not called grey-scale

but could be called monochrome. 2. A range of

accurately known shades of grey printed out for

use in calibrating those shades on a display or

printer.

HSV: Hue,

saturation, value. A colour model that describes

colours in terms of hue (or "tint"),

saturation (or "shade") and value (or

"tone"). Image: Data

representing a two-dimensional scene. A digital

image is composed of pixels arranged in a

rectangular array with a certain height and

width. Each pixel may consist of one or more bits

of information, representing the brightness of

the image at that point and possibly including

colour information encoded as RGB triples. Images

are usually taken from the real world via a

digital camera, frame grabber or scanner.

JPEG:

Joint Photographic Experts Group. The original

name of the committee that designed the standard

image compression algorithm. JPEG is designed for

compressing either full-colour or grey-scale

digital images of "natural", real-world

scenes. It does not work so well on non-realistic

images, such as cartoons or line drawings. JPEG

does not handle compression of black-and-white (1

bit-per-pixel) images or moving pictures.

Monochrome: Literally

"one colour". Usually used for a black

and white (or sometimes green or orange) monitor

as distinct from a colour monitor. Normally, each

pixel on the display will correspond to a single

bit of display memory and will therefore be one

of two intensities. A grey-scale display requires

several bits per pixel but might still be called

monochrome.

Pixel:

Picture element. The smallest resolvable

rectangular area of an image, either on a screen

or stored in memory. Each pixel in a monochrome

image has its own brightness, from 0 for black to

the maximum value (e.g. 255 for an eight-bit

pixel) for white. In a colour image, each pixel

has its own brightness and colour, usually

represented as a triple of red, green and blue

intensities.

RGB: Red,

Green, and Blue. The three colours of light which

can be mixed to produce any other colour.

Coloured images are often stored as a sequence of

RGB triplets or as separate red, green and blue

overlays though this is not the only possible

representation (see CMYK and HSV). These colours

correspond to the three "guns" in a

colour cathode ray tube and to the colour

receptors in the human eye. Often used as a

synonym for colour, as in "RGB monitor"

as opposed to monochrome (black and white).

TIFF:

Tagged Image File Format. A file format used for

still-image bitmaps, stored in tagged fields.

Courtesy:

FOLDOC, UK.

|

|

![]()