Damned or

doomed?

By Peeyush

Agnihotri

LARGELY due to the human attitude

of "neglecting those who bequeath," quite a few

earthen dams dotting the Shivaliks, which not long ago

hogged media attention for showering prosperity upon the

area, are dying...... if not already dead.

Earthen dams, which form an essential part

of the integrated watershed management programmes, have

proved to be a boon for such villages which had remained

enveloped in the darkness of stark poverty. Not only did

they vitalise rural economy, they rehabilitated the

degraded eco-system as well. Earthen dams, which form an essential part

of the integrated watershed management programmes, have

proved to be a boon for such villages which had remained

enveloped in the darkness of stark poverty. Not only did

they vitalise rural economy, they rehabilitated the

degraded eco-system as well.

Tragically, these

"watering holes" of the Shivaliks met their

Waterloo due to neglect, lackadaisical approach, apathy

and fund scarcity. What looked like jaded jewels in the

topography’s crown till yesterday, appear as ugly

smallpox scars on the hills’ weather-beaten face

today.

Spearheaded by a team of

scientists from the Central Soil Conservation Institute,

under the aegis of ICAR, what started as an innovative

experiment from Sukhomajri village in 1978 soon became a

concept and was emulated by state governments to

ameliorate the economy of other poverty-stricken

villages. Overwhelmed by the response that this project

elicited, various government and non-government agencies

pitched in, rather hastily, to replicate such projects in

other semi-hilly villages of Shivaliks. Some worked,

others failed, rather miserably.

Typically, earthen dams

are constructed with earth collected from the upstream

side of the probable dam sites. Site selection is

important for economising on cost. If a dam site is

located on a narrow gorge, it is considered ideal as

strong stable sides support the structure. The

feasibility also depends on the catchment area, rainfall

intensity and discharge. Catchment is the feeding area

from where water can be harnessed to reach the dam. If

there is a spillway site, preferably a natural, on one

side of the chosen site, but at a safe distance from its

body, it is considered ideal.

Once the dam is

constructed by government agencies, it is ultimately

handed over to village societies, which act as its

guardians. They collect revenue from the beneficiaries.

Though the money so earned is just sufficient to maintain

a dam, it is not enough for undertaking major repairs. In

case of a snag, rural brethren are left with no choice

other than to ask the government for funds.

Built barely two years

ago, the dam at Asranwali, 25 km from Chandigarh, has

already started inching towards decay. The dam could

provide water to 20 acres of land till a year ago. Today,

the water discharge has decreased. "Due to utter

neglect, mud has seeped in pipelines and we could

irrigate our wheat-sown fields just once, " remarks

Ilmdin, a resident of the village.

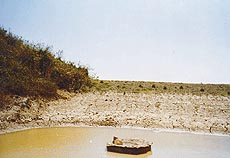

A visit

to Nada village, 10 km from Chandigarh, was an

eye-opener. Dam III at the village is no more. This dam

was the talking point a few years ago as it had

transformed the economy of the village. It is noteworthy

that the dam is located near a Dalit settlement. Today,

the sidewalls have caved in and the depression holding

the water reservoir, which has been taken over by weeds

and wild growth, has become a bucolic lavatory, besides

acting as a grazing ground for cattle. A visit

to Nada village, 10 km from Chandigarh, was an

eye-opener. Dam III at the village is no more. This dam

was the talking point a few years ago as it had

transformed the economy of the village. It is noteworthy

that the dam is located near a Dalit settlement. Today,

the sidewalls have caved in and the depression holding

the water reservoir, which has been taken over by weeds

and wild growth, has become a bucolic lavatory, besides

acting as a grazing ground for cattle.

Dam V in the village

standing 12-metre tall has a catchment area of 45

hectares. The spillway broke two years ago. Today, the

government after waking up from slumber, has started work

on it. Needless to say, the work is moving at a

snail’s pace. "Silt deposit has taken its toll.

The delivery pipe is choked and we are siphoning off

water, " says Somvir, the guard who oversees the

dam.

Slope of Dam IV has

cracked and the underground pipe is choked. Dam VII in

the village has the same story to tell.

Name of the villages

change. But the story remains the same. Five dams were

constructed in Chauki village. Only one, constructed two

years ago, is in working condition. A dam, constructed in

1984, has eroded. Dams constructed along Landi choe

and Bagon nullah are now no more.

Many of the dams were

"killed" due to the heavy siltation rate, while

others were washed away due to improper design and

execution. And there are some which did not function due

to faulty site selection.

While villagers blame

the government for not maintaining dams, government

officials blame village-level societies, which are

usually asked to act as the dam’s guardians, for

upkeep of the dams built by them. "Village politics

too plays a negative role in some cases," asserts

Rajinder, a Haryana government official.

Most of the government

departments had an evasive attitude on the subject.

"We are not the sole government body engaged in

repair of faulty dams. The allocation of funds for

rectifying a snag-hit dam always depends on what we get

from time-to-time," says a Haryana-based Project

Director of a World Bank- aided project.

"There are around

120 dams dotting the Shivaliks and only 60 per cent of

them are in working condition," says Banarsi Das,

Principal Chief Conservator of Forests, Haryana.

"Sometimes the dams fail due to human error, like

bad location or less siltation which does not provide

effective bed-sealing to the dam. But, in most cases it

is due to the negligent attitude of village societies,

which do not care to rectify minor faults, that dams

suffer irreparable losses," he laments. "We are

not asking for the moon but they can at least provide us

with the manpower whenever we require it for repair

purposes," he adds.

Whatever be the case,

land-tillers and villagers are disillusioned and are

bearing the brunt of a pass-the-buck policy. They have

seen dam after dam crumble and now want to resort to

tubewell irrigation. "We tell them that tubewell

irrigation is not feasible in hilly tracts due to deep

groundwater and undulating topography, but villagers, who

have seen the fate of dams, have developed a sort of

mental block against such type of irrigation and water

storage method," asserts a social scientist

connected with the watershed management programme.

Officials of the

Department of Agriculture, Haryana, say that not always

do they "design, build and forget." "We

review the case in every problematic village. If the

village society has enough money, we ask it to bear the

cost of the repairs. Otherwise we pitch in. But that

always depends on the availability of funds," says a

technical official of the department.

He adds that due to such

dams, the ground water recharge has been phenomenal.

"People on the foot hills have started levelling

their fields to dig tubewells because of this," he

says.

P.R. Khusru, a dam

design engineer of the same department, says that it is

usually some natural factor beyond human control like

heavy rainfall, rather than faulty designing, which

causes the demise of a dam.

Nature, too has some

role to play in this game of "build and break"

"Geologically speaking, these hills are of the

Pleistocene age and lithologically composed of

sedimentary rocks, loose boulders and clay. So, heavy

rainfall would always mean heavy erosion, " remarks

Dr Naval Kishore Sharma, a faculty member in the

Department of Geology.

Banwari Lal, one of the

executive member of the water users’ society of a

village, came out with a novel suggestion. "The

government can give some money to the society for repairs

when they hand over the charge of the dam." New

Centre-sponsored schemes to revive sick dams can also

help, he adds.

Are the villagers damned

or is their future doomed? While accusations bounce back

and forth like a ping-pong ball, it is the village

economy and farmers who suffer. Balku Ram, a poor

shepherd from Nada village, sits dejected near what used

to be a dam not long ago and pleads to every government

official who visits the site, "Babuji, isda kuch

karo," (Sir, please do something about it). This

sums up an average villager’s desperation.

|

![]()