|

|

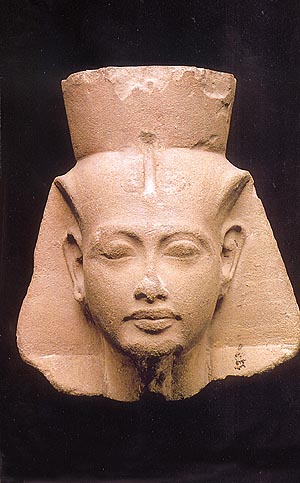

FOR close to a mile before one gets to the famed County Museum of Art in Los Angeles these days, one starts noticing giant posters announcing yet another exhibition which is bringing in enormous crowds to the place. Filling them, against an intense, velvety black ground, is an elegantly carved pharaoh’s head, in true profile, of the kind that one sees so often from Egypt: in an understated pink-brown sandstone, crisply articulated, monumental yet delicate, features – sensuous lips, ridged nose, fish-shaped eyes, noble forehead – that imprint themselves quickly upon the mind. "Pharaohs of the Sun" is how the exhibition is titled, with three names that reverberate through the history of ancient Egypt – Akhenaten, Nefertiti, Tutankhamen – serving as a sub-title. The head on the poster belongs to the first named of the three, and the viewer – especially one who can recall to his or her mind the great Tutankhamen Treasures exhibition which set the trend for mega-shows some 20 years back – prepares to have yet another mind-expanding experience. |

|||||||||

How many people come in anticipation of

receiving that experience is truly astonishing. For all

the days that I was there – it was a three-day

workshop dedicated simply to "looking" at

Indian paintings that I was involved in – I saw

enormous throngs of men, women and children, many of them

members of groups that had come from long distances, come

and excitedly gather at the entrance, standing in queues

for hours together before being able to get in, for only

limited numbers could be allowed inside the exhibition

galleries at one time. Placards clearly marked the

different queues: those due to be let in at 10-30 a.m.

stood in one, while those scheduled for 11-30 a.m. were

in another, for instance. I was spared the effort, having

been given, as a guest of the Museum, a special entry

pass that allowed me to enter and come out at will. But,

once inside, I was like any other member of the crowd:

squeezed into limited space, even jostled at times. For

the galleries were packed, viewers – many of them

with ‘acoustiguides’, taped information played

into the wearer’s ears through headphones –

moving slowly from one object or show-case to another,

holding brochures in their hands, carefully reading the

detailed information panels which dotted the walls,

pointing things to each other, looking, constantly

looking, with awe and wonder at the artifacts displayed.

I wouldn’t say that I felt wholly comfortable with

such crowds around me, but the mere sight of so many

people interested in the experience that the art of even

a remote and alien culture yields, soaking in

information, was in itself energizing. No one, who has

only seen the pitiably thin crowds that even the best of

art exhibitions in our own land attract, can possibly

imagine the sight. Here were people, an enormous number

of people, eager to extend the horizons of their minds,

hungering to receive. How many people come in anticipation of

receiving that experience is truly astonishing. For all

the days that I was there – it was a three-day

workshop dedicated simply to "looking" at

Indian paintings that I was involved in – I saw

enormous throngs of men, women and children, many of them

members of groups that had come from long distances, come

and excitedly gather at the entrance, standing in queues

for hours together before being able to get in, for only

limited numbers could be allowed inside the exhibition

galleries at one time. Placards clearly marked the

different queues: those due to be let in at 10-30 a.m.

stood in one, while those scheduled for 11-30 a.m. were

in another, for instance. I was spared the effort, having

been given, as a guest of the Museum, a special entry

pass that allowed me to enter and come out at will. But,

once inside, I was like any other member of the crowd:

squeezed into limited space, even jostled at times. For

the galleries were packed, viewers – many of them

with ‘acoustiguides’, taped information played

into the wearer’s ears through headphones –

moving slowly from one object or show-case to another,

holding brochures in their hands, carefully reading the

detailed information panels which dotted the walls,

pointing things to each other, looking, constantly

looking, with awe and wonder at the artifacts displayed.

I wouldn’t say that I felt wholly comfortable with

such crowds around me, but the mere sight of so many

people interested in the experience that the art of even

a remote and alien culture yields, soaking in

information, was in itself energizing. No one, who has

only seen the pitiably thin crowds that even the best of

art exhibitions in our own land attract, can possibly

imagine the sight. Here were people, an enormous number

of people, eager to extend the horizons of their minds,

hungering to receive.And receiving they were in ample measure. For the exhibition is rich, and finely textured. I know something about the art of Egypt, having studied it in a small manner, and having seen collections of it in major museums across the world, including the great one in Cairo, but what I was able to see here, within the ambit of its sharp focus, was truly exciting, both intellectually and in visual terms. Instead of giving a general overview of the art of Egypt, this show took a very carefully delimited area – the reign of the Pharaoh Akhenaten who ruled in the fourteenth century B.C., and the innovations he introduced in the areas of religion and art – and trained a sharp shaft of light upon it, thus throwing up issues and ideas, and making a period – and some important personages – come alive. It was done, however, not through words alone – the information panels only served to establish the appropriate contexts – but, as is wholly appropriate to an exhibition of art, through the range and the quality of the objects incorporated in it. If the texts, interpreting those mysterious, magnificent hieroglyphs, spoke of the pharaoh Akhenaten having introduced the worship of Aten, "the light within the Sun’s disc", one saw it so vividly also in visual terms, with sculpted reliefs showing the rays of the Sun descend and bathe everyone, from king to humble subject, in their glorious light. Likewise, if there was mention of a shift in the style of art under Akhenaten, there was object after object that made the point: colossal portraits of the pharaoh himself, and large and small ones of his beauteous consort, the Queen Nefertiti; large and descriptive panels featuring ordinary men and women with their long, angular faces, narrow torsos and voluptuous hips; even small fragments with lightly incised but unbearably graceful renderings only of hands and feet. One saw majesty and grandeur, sheer power and the raw texture of daily living, closeness to life and the ambition to soar above it all. But there was nothing in the exhibition to suggest that all one saw in it was close-ended, or that all problems relating to those distant times had been solved by scholars. Questions remained, and loomed over each attentive viewer as he left the exhibition. Whatever happened to the city of Amarna that the great pharaoh founded? Who indeed were Nefertiti’s parents, and did she rule for a while after Akhenaten’s death? Who was the direct successor of Akhenaten, and why were the city he founded, and the religion he favoured, erased within a few years of Akhenaten’s death? Hymns to light Curiously reminiscent of the hymns to the Sun in our own Vedic texts, and in some ways of some psalms in the Old Testament, are many of the moving verses that Akhenaten is believed to have composed himself to Aten, that "Light within the Sun’s disc" which he paid such homage to. "How

various is the world you have created, It is as if there were unseen connections. |