| |

Dons and don’ts of

Oxbridge

Of the shelf

by V.

N. Dutta

NOEL Annan (1916-2000) was

easily one of the brightest and most influential

teachers of political theory at Cambridge in the

early 50s of last century. His erudition, clarity

of thought and lucidity of expression were widely

admired. He firmly believed in the power of

words, and said so. He possessed remarkable

literary skills in putting things in a dramatic

way. He regarded Edward Gibbon and Lord Macaulay

as the greatest historians the world has produced

despite their prejudices and sureness of touch.

His classes were largely attended, and his

personal contact with his pupils acted as a great

intellectual stimulus on their life, and he

remained closely in touch with some of them even

after they left the university.

At 26 Noel Annan

was a lieutanent-colonel in the army handling

some sensitive issues of war. At 39 he became

provost of the prestigious King’s College,

Cambridge, and was later head of University,

College, London, and Vice-Chancellor, London

University. He was a trustee of the British

Museum. His 1977 report proposing radical reforms

in public broadcasting was greatly appreciated.

The book under

review is his last work which appeared before his

death: ‘‘The Dons: Mentors, Eccentrics

and Geniuses" (University of Chicago, pages

358, $ 30). The brilliant and witty literary work

of intellectual history which illuminates the

contributions of Cambridge and Oxford dons is a

sequel to his earlier work "Our Age:

Portrait of a Generation".

Annan’s

special field of interest was western political

thought. His range was not as wide as Bertrand

Russell’s. Nor was he scientillating like

Carl Becker. He could not equal Michael

Oakshott’s rigour of thought and

incisiveness. He did write essay after essay like

Isaiah Berlin. His works were distinguished for

their exquisite lucidity and glittering prose but

lacking G.M. Young’s depth of scholarship

and sobriety of judgement.

Annan’s

earliest work was a biography of Leslie Stephen,

which he wrote when he was 37. This study had a

mixed reception. His admirers thought it a

literary tour de force and his critics

panned it for focussing on the personality to the

neglect of social and political forces that

operated. His contribution by way of articles in

prestigious journals was substantial. He produced

two notable studies, "our Age", a

comprehensive and entertaining survey of the

intellectual aristocracy of his own generation

and "Changing Enemies: The Defeat and

Regeneration of Germany" (1996), an account

of his experiences during the war when he was

very near the top of allied intelligence.

The book under

review, "The Dons", ends with the

inclusion of Annan’s celebrated essay.

"The Intellectual Aristocracy", which

had established him as one of the leading

historians of social thought. This work had

traced with remarkable ingenuity and tenacity the

intermarriages and literary associations of the

Macaulays, Darwins, Stephenians and Butlers over

two centuries and more, which left a profond

impact on the age. This work is a collection of

historical and biographical essays on some of the

outstanding dons at Oxford and Cambridge. The

term don stands for a university teacher,

especially a senior member of a college at Oxford

and Cambridge.

According to

Annan, a don was a scholar who conducted private

tutorials for his pupils, had dinner in the

common hall and identified his life with the

tradition of, say, Balliol, King’s or Christ

Church College. At their best, such figures

cultivated, trained and exercised their own

intellect as well as of their students.

Annan’s gallery of colourful portraits of

dons may have special interest for those who love

learning for its own sake, but to many such types

seem odd and outdated in the topsy-turvey world

of today where material values reign supreme.

Annan cites

several examples to emphasise that dons sought

and valued knowledge and encouraged their

students to do so. Annan quotes the famous Greek

scholar and Master of Balliol College, Oxford,

Benjaman Jowett, whose work on Plato is

authoritative. Jowett insisted on the delight of

hard work". Jowett himself was a

solid scholar, of classical studies. He said,

"The object of reading is not primarily to

obtain a first class (degree) but to elevate and

strengthen the character of life — the class

matters nothing. What does matter is the sense of

power which comes from steady

working’’. Such an approach was part of

literary education which Francis Bacan had

advocated as a foundation for a free play of

thought. It is by solid hard work and

self-cultivation that great minds are formed.

This

approximates to the utilitarian theory of

education popularised by Bentham. No lesson is

more important to a student in a university than

working one’s own way through efforts and

building internal resources through self-reliance

and tenacity of purpose uninfluenced by external

pressures. Annan writes, "The steady

accretion of knowledge, the focussing of all

one’s energies on some problem in history or

science, the dogged pursuit of excellence —

these are the right and proper scholarly

ideals."

Annan shows that

quite a number of dons immerse themselves in

specialised studies of a narrow range which have

a limited appeal in academic circles. On the

other hand, glittering prizes go to the

wordly-wise and the politically astute, the lucky

and the charismatic. To this category belonged

literature professor Maurice Bowra, political

philosopher Isaiah Berlin and Shakespearean

scholar George Rylands. J.J. Thompson, Henry

Newman and James Harrison, however, dazzled

because of their sparkling intelligence.

Annan gives an

insightful account of some of the foibles and

eccentricities of Maurice Bowra who was a man of

strong likes and dislikes. Bowra pursued his

enemies relentlessly. Annan writes, "When

Bowra gave the oration at the memorial service

for his old tutor Alec Smith, the air was so dark

with the arrows he dispatched, like Apallo

spreading the plague among the Grecian host

before Troy, that you half-expected groans to

arise from the congregation and the guilty to

totter forth from St Mary’s and expire

stricken on the steps of Redcliffe."

Annan writes

little on Bertrand Russell. Of course, there was

not much to write on him as a don because his

stay at Cambridge was short due to his forced

resignation as a Fellow of Trinity College,

Cambridge, on account of his pacifist convictions

during World War-I.

There were a

number of dons who divided their time between

their administrative responsibilities and

academic interest. Such dons did not think that

their divided loyalties would in any way diminish

the quality of their academic contributions.

Annan himself belonged to this type because he

spent much of his time as a high-ranking

university official, engaged in administrative

work. For such persons Master of Trinity Richard

Jebb, Regius Professor of Greek, Cambridge,

quipped: "What time he can spare from the

adornment of his person he devotes to the neglect

of his duties."

There are

several accounts in this book about the intrigues

and petty jealousies among the dons who spurred

by their vaulting ambitions and enormous personal

vanity, used ignoble means to perpetuate their

interests in academic and public life. Annan

explores the cult of homosexuality and the new

morality that some of the dons preached. He shows

also how some of them during the days of

appeasement and Munich became Marxists and

handful of them Soviet spies.

According to

Annan, despite some liberal historians, others

were stout conservatives of Cambridge and Oxford.

The history faculties were mostly a "nest of

Tories and Christianity", out of which

tumbled Herbert Butterfield, Trevor-Roper and

Maurice Cowling. Michael Oakshott challenged the

philosophical and political traditions, and the

famous English don F.R. Levis launched a virtual

crusade against the moral and literary traditions

of the age.

Annan has

showered much praise on Lord Keynes who had

assembled what he called his circle in which the

star performers were Richard Kahn, Joan and

Austin Robinson, and Piero Sraffa. This group of

luminous intellects was acknowledged as the most

remarkable in the humanities faculty in Cambridge

between the wars.

|

| |

Sai Baba: more books from

devotees

Review

by P.D. Shastri

Shri Sai

Baba — The Unique Prophet of Integration by

Satya Pal Rohela. Pages 391. Rs 150.

A Solemn

Pledge from True Tales of Shirdi Sai Baba by B.H.

Briz Kishore. Pages 82. Price not mentioned.

THE first one is an

authoritative work on Sai Baba of Shirdi. Its 41

chapters have been contributed by different

devotees — Sai specialists all — though

there are some repetitions. The editor, Prof

Satya Pal Ruhela, who has already written 15

books on Shirdi Sai Baba, contributes six

chapters, while Narasimha Swamiji, who has

published "Life of Shirdi Baba" in four

volumes, contributes four.

Shirdi Sai Baba

was a Muslim saint though most of his massive

following consists of Hindus. At Shirdi, their

place of pilgrimage, some 25,000 persons visit

every day and there is hardly any Muslim-looking

person. Even B.V. Narasimha Swamiji, one of his

chief disciples, concedes: "It was extremely

difficult for this writer to find even one person

(Muslim) who had got in spiritual touch with

him."

He lived all his

working life in a dilapidated mosque; he wore the

dress of a Muslim faqir; his disciple Abdul read

the Quran to him. He spoke of Allah and Allahu

Akbar. Of the 41 contributors to this book, only

one has a Muslim name.

When he died, he

was buried in a grave like a Muslim, not cremated

like a Hindu. He is every inch a Muslim. His

followers quote him as a unique prophet of

integration. He brought together the two major

communities, the Hindus and the Muslims together

(really?). In the 17th century Samarth Ramdas,

the guru of Shivaji, had performed a similar

feat, but after a few years, the effect of his

preachings wore off. So God sent yet another

prophet of integration. The Shirdi Baba’s

chief mission was to weld the two major

communities and cement their relations by setting

a personal example. He worked for peace.

Of course,

Muslims did not like his unorthodox ways. He was

striking at the root of the orthodox Muslim

tradition. They objected to his desecration of a

Muslim masjid, with Hindu artis and other

celebrations like Ram Navami. More than once,

some Pathans came to murder him for his apostasy,

but he was protected by his divine powers.

Even among his

vast Hindu following, his Muslim way of life

created confusion, even opposition. The Hindus

had no end of avatars, prophets, apostles, sages,

saints, gurus and what not? Why should they go

out of that endless circle to become the disciple

of a Muslim faqir?

A Brahman doctor

from South Africa won’t bend before a Muslim

faqir. When he did bend, he saw in Shirdi Baba

the image of his Ram.

One Megha, a

poor illiterate Brahman, had objection to bowing

to a Muslim saint. When he saluted the Shirdi

Baba, he saw in him the much worshipped

incarnation of Shiva. He is placed along with

Rama, Krishna, Hanuman, Christ and the Buddha (he

is the incarnation of the millennium) but not

Muhammad for Muslims would not take it.

And so on for

other dissidents.

Scholars were

busy mending the fences. Their researches

(invention?) showed that the Shirdi Baba was born

of Brahmin parents. His father’s name is

given as Ganga Bhavadi and his mother’s Dev

Giri. The father became a recluse and left home.

His mother went in search of him (she died when

her son was 12). A Muslim faqir adopted the

orphan boy and thus the Baba’s Muslim way of

life.

Another theory

floated by such apologists is that the Baba spent

one night in his mosque and the second night in a

temple. There is hardly any proof of it. At any

rate no temple is a second Shirdi mosque.

He claimed to be

Kabir in one of his previous births. (Kabir was a

Muslim weaver and poet who spread the cult of Ram

Nam.) He named his masjid "Dvarika

Mai", to give it a Hindu name. He also

quoted from the Gita and other Hindu scriptures.

He is the prophet of secularism.

He was neither a

Hindu nor a Muslim, but a divine messenger of

humanity, above all narrow differences. He taught

the universal religion of love. His mission was

the atmic (spiritual) integration of the

whole mankind.

Another event

also helped his cause. Satya Sai Baba, a boy of

14 in 1940, threw away his school books and said,

"I am Sai Baba come to save the world.

Shirdi Sai Baba was the Muslim Sai, I am the

Hindu Sai and eight years after my death will

come Prema Sai, the Christian Sai. Thus the Sai

movement represents Hindu, Muslim and Christian.

This support of Satya Sai Baba greatly helped

Shirdi Sai to find a place in the hearts of all.

Thus Shirdi Sai

became a household deity in countless homes. Our

book says, his disciples are growing in

astronomical proportions. The Baba had come to

Shirdi at the age of 16 and sat under a neem

tree. He lived there for 60 years. His literature

is growing in the USA, Canada and Australia. Sai

temples are coming up all over India and abroad

with the greatest number in Andhra Pradesh. One

such temple in Mumbai (Panvel) has a bronze

statue donated by foreign devotees. It is a

27-ft-high statue of the Shirdi Baba, claimed to

be the tallest Sai statue in the world. There are

2000 Sai temples in India and 150 abroad. All

rivers merge into the ocean, so salutations to

all gods and gurus reach the Shirdi Baba.

This book

presents the Shirdi Baba as a God incarnate. To

give some quotations: he was never born, never

died, an immortal saint. He is ever living.

The Shirdi Baba

is purna avtar (perfect incarnation). He

is the foremost avatar of the kali age.

His name and fame surpass the popularity of any

godman or mystic. He is presented as the creator,

preserver, destroyer (Brahma, Vishnu and Mahesh).

"All great

men in India and abroad have accepted Sai Baba as

god incarnate." By his grace the life cycle

of universe is running.

The words put in

his mouth also proclaim him to be Lord God

himself.

For instance,

"I am present even before the creation.

"I am prime

God.... I am the permanent soul of the whole

universe.... I am present in all beings."

"He used to

beg alms, but Goddess Lakshmi was his maid

servant..."

"If a man

utters my name, I shall fulfil all his

desires."

In the last

chapter, the Shirdi Baba is presented as

omnipotent (33 points in support) and omnipresent

(12 proofs), omniscient (21 points in support).

All godmen live

on the strength of the miracles they have

performed, which attested to their powers. Our

Baba cured hopeless and incurable cases. A boy

had polio. At his touch, the boy started walking.

The Baba took

someone’s plague on himself and the patient

was cured.

Childless

couples got children, one couple got eight. Those

in search of wealth were flooded with money and

property. All their heart’s desires were

fulfilled.

A devotee was

going to Prayag for a holy dip. The Shirdi Baba

produced waves of the Ganga and the Yamuna from

his toes.

Most disciples

come to godmen in search of these prizes of life.

(In this age of miracles of science, technology,

medicine, etc, a rationalist would say that such

cures and miracles are a common place. But the

devotees are sure that their guru caused them

all.)

He lighted lamps

with water, without oil — that is a popular

miracle.

As you enter his

shrine at Shirdi, you see a huge board with his

11 promises: The first is: "whosoever puts

foot on Shirdi soil, all his sufferings would

come to an end." The last one is:

"There shall be no want in the house of my

devotee."

Since there are

41 chapters on the some aspects of one godman,

there is sure to be endless repetition and

overlapping.

To the devout,

these strengthen the faith, but to a common

reader so much repetition tends to be boring.

Also all these writers are men of deep faith, not

men of letters. These writers have turned authors

and hope to surely win all prizes of life,

through the Shirdi Baba’s special favour.

The book is

crammed with the names of a large number of

nonentities who received the Baba’s favours.

It is all due to Shirdi Sai Baba that they

received his favours and so much publicity in Sai

literature.

His guru gave

him no guru, mantra and so he gives none to his

disciples like other godmen. He taught the world

by his personal example, not by delivering or

writing sermons.

The book

"Sai Sad Charita" is the bible and the

Quran of the Sai sect. Intellectuals and

rationalists feel bewildered by the phenomenon

that defies scientific attitude and modernism.

There has cropped up so many godmen on the

world’s stage with a clientele running into

millions, including some highly learned men and

famous names. Former President V.V. Giri is one

of our contributors and another is a High Court

Judge. Foreign followers add special glory to the

guru. The fact is that in the present

"cruel" world, there is so much

tension, frustration and heart-ache even for the

top men. The guru promises peace, happiness,

fulfilment of all desires in return for

one’s surrender to him. And when

self-interest develops faith rationalism and high

sense of absolute truth go to sleep.

«

« «

The second book

"Solemn Pledge from Tales of Shirdi Sai

Baba" covers the same ground, but on an

humbler scale and with men of slighter build. The

Baba’s miracles includes curing cases of TB,

epilepsy, cholera, malaria, stomach ache and ear

pain. He took a boy’s plague on himself and

the boy was cured. The Baba blessed them with udi

(ashes as Satya Sai Baba does). He could control

the fury of storm, flood and fire. He lit earthen

lamps without oil, only with water. He was

present everywhere and in everyone. He knew the

past, the present and the future.

He fulfills the

wishes and desires of all; his treasure is

inexhaustible. He gave mangoes and childless

women became pregnant. Astrological predictions

forecast troubles. The Baba saved his devotees

from these predicted troubles.

This book has an

effective page count of 82; which means 41 pages

for opposite every small printed page, there is a

page of a picture as illustration. Smaller men,

lesser miracles — that is the story of this

book. Call it a booklet or pamphlet, not worthy

of being entitled a standard work. However, his

love for the Shirdi Baba seems to be as great as

of any other devotee.

|

| |

Sketches in scintillating

poems

Punjabi Literature

by

Jaspal Singh

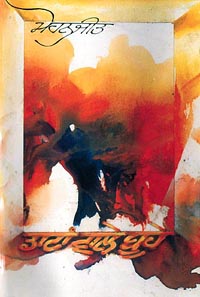

MOHANJIT is one of the

finest poets of Punjabi though underrated by most

critics. As a native of Majha, he ought to be

dynamic and even manipulative in self-promotion.

But by his way of life, he displays a different

disposition. He is almost always calm and

composed, lost in his creative meditation as if

dreaming all the time.

His first collection of

poems, "Sahikda Shaher" (the dying

city) appeared in the early seventies. After that

he has brought two more collections of poems, a

book on stylistics and seven books of translation

from various languages. His first collection of

poems, "Sahikda Shaher" (the dying

city) appeared in the early seventies. After that

he has brought two more collections of poems, a

book on stylistics and seven books of translation

from various languages.

But the form

that he brought to near perfection is the

pen-portrait in verse of many modern Punjabi

writers and artists. Three collections of such

poetic sketches have appeared so far, starting

with "Turde firde maskhare" in the

mid-seventies. Then appeared "Gurhi likhat

wala varka" and the latest "Dattan wale

buhe" (Lok Sahit Parkashan, Amritsar).

The latest

collection comprises 38 sketches. Rajinder Singh

Bedi, a Urdu writer, Krishna Sobti, a Hindi

writer, and Khushwant Singh, an English writer,

have their share of spotlight in the galaxy of

illustrious figures. A powerful Pakistani woman

poet, Saara Shagufta, too is included to provide

variety to the already over-spiced write-ups.

Some of the

sketches have appeared in earlier collections as

well. But to make the present one more

representative, they again make a re-appearance.

Rajinder Singh

Bedi is "an epic written on worn out

palms", whom a whore visited every day with

the words, "your beard is like a dog’s

tail, old man". Towards his end he visited

her brothel and said, "Every beard is not a

dog’s tail, gentle lady". He was a

writer whose touch could consecrate the obscene

and make the reader cry even through his

salacious accounts. He lived among the milling

metropolitan crowd, as if eating fresh corncobs

sitting in a secluded maize field.

The poet has an

intense desire to have a meeting with Amrita

Sher-Gill who died long ago, leaving behind some

of the finest paintings of the epoch. He wants to

have a feel of the ultimate fort of her egotism.

But now he has imagination only to spin the

dreams and emotions, body organs and lyrical

sounds, that speak through the language of her

artistic touches. Life for her was made of

colours, both fast and fading, sometimes letting

out a mournful cry. It was resplendent yet

vacuous. she was vivacious yet sad. Her paintings

were gloomy self-portraits.

Khushwant Singh,

the poet says, rides an untamed

"wind-horse". Once a friend, always a

friend. He dares speak when none can open his

mouth and there is turbulence all over. Rivers

were full of blood and forests were in raging

fire. One could speak only at the risk of his

life and Khushwant Singh spoke at the highest

pitch of his voice. Three cheers for the old man!

Krishna Sobti

for Mohanjit is a merchant’s wife who lives

in a mansion and who hurls virulent abuses at

those who dare to cross her path. Her abuses are

veiled but her actions are transparent. She does

not fill her room with petit bourgeois kitsch,

rather sweeps it off if there is any. She weaves

and wears a pullover of brusque utterances to

save herself from the numbing cold. She walks on

the thorns of meanness, crushing them under her

feet. Many of her virgins with coiffeured hair

have become the adornment of the market place,

yet she goes around in search of pearls in

darkness with a lantern in hand

One of the best

portraits is that of Saara Shagufta, an enigmatic

Pakistani woman poet. She was a Quranic verse

engraved on the sands of time. The poet says,

"When you grow out of your clothes and the

female body comes into itself eyes grow all over

it." She descended on Delhi, with a heavy

cloak around her, though nude in demeanour —

wild, brusque in speech, furious, indifferent,

careless, unused yet overused like a mud track.

At times she would burst into laughter as if she

would die of it. One had to constantly guard

against her. All her symptoms were anti-life.

Like a fish she flapped her tail, bouncing and

jumping on the river bank. She drew pleasure from

burning her fingers. She came with a smouldering

womb and a flaming poem.

So was Puran

Singh, whose rhyme had the openness of the sky.

With Punjab ensconced in his heart, he galloped

like the Guru’s horse. His eyes had both the

Ganga and the Mansarovar hidden in them. His

words were like thundering clouds. He was the

indifferent rider of a wild horse who would blow

in the wind the baloon of worldly trifles. He was

the flow of the Sutlej, the expanse of the

Attock, the landing place of the Chenab and the

current of the Ravi. The Gangotri broke out from

his "samadhi" (mystic trance). His

freedom was his restraint. His rage was like a

flashing sword and his patience like the

Sukhmani. He was the hermitage of the

"fakirs", knoll of the

"yogis", congregation of the devotees

and the conclave of the rebels.

Nanak Singh,

according toMohanjit, was "sharbat" of

jaggery and Devinder Satiarthi is the modern

Gorakhnath. Sometime Satiarthi is a Brahmin and

at others a cattle-breeder. All the seals of the

Indus Valley civilisation have his figure on

them. He is a horse at one place, an ox at

another and a rhinoceros a little farther. The

11th head of Ravana is his forehead. He is in

eternal exile; that is why he has not left his

wooden sandals behind.

Amrita Pritam is

a garland of flowers. Her look can make or mar

one at the same time. Many vendors traversed her

street with glass baskets on their heads.

Somebody polished his shoes before hawking his

wares. Some other applied antimony to his eyes to

gather courage in them. Had somebody gone with

the truth in his heart, she would not have called

the dead Waris from the graves.

Sant Singh

Sekhon was a bottle with a worn out label but

which had the fragrance of all the essences of

the world. He sizzled if heated and froze if

cooled. "Sekhon" was his qualification;

all else was opinion. Poem, for Mohan Singh, is a

burning lamp in wilderness. The author

says:"I have not seen him playing chess but

in his poems I have seen pawns and knights

drinking a rice-brew while sharing the same

mat."

There is a very

fine sketch of Bawa Balwant who died on the

street in Delhi. The author says about him:

"The manifest light of poetry is lying

motionless on the road in the searing heat of

summer and by his side lie his friends in exile

— his cloth bag and his umbrella. The bag

still carries the unrealised dream of a pearl

necklace. The endless train of thoughts still

goes on. The inner light still glows. The priest

is dancing in trance. The wielder of the pen

keeps on writing while sitting in his brooding

attic. His shoes are worn out yet the tale to

transform the world goes on endlessly."

Haribhajan

Singh, according to Mohanjit, lies on a wooden

cot with steel posts and his head lies on the

pillow of nails and yet he is sound asleep. He

now has stored his old portraits in the

refrigerator and has pasted silver paper on the

new ones. He sits under the shadow of the skirt

worn by an old witch and asks his cohorts to

shear her tangled locks. He has stolen

Nero’s fiddle and the Romans have no inkling

of it.

Kartar Singh

Duggal is the Chenab of creativity and Dilip Kaur

Tiwana a cascade of silence. Attar Singh is a

coat of mail worn by a chair. Ajit Cour is the

henna from the black orchards. Sukhbir, Prem

Parkash, Gursharan Singh, Jagtar, Harnam, Shiv

Kumar Batalvi, Harbhajan Halwarvi, Parminderjit,

Surjit Patar, Noor, Amarjit Chandan and quite a

few other Punjabi writers are commented upon

through these verse pieces.

Those who know

something about them will immensely enjoy the

verse since many metaphors and anecdotes

associated with these acteurs are subtly

sprinkled here and there. Only a gifted poet like

Mohanjit could do justice to such complex

personalities.

|

| |

Sadly, sadly in verses

Review

by R.P. Chaddah

The

Aching Vision — Poems by Darshan Singh

Maini. Writers Workshop, Calcutta. Pages 182. Rs

200.

THE book under review is

Dr Maini’s third book of verses in the past

10 odd years. It contains about 150 gloomy bunch

of poems which detail various manifestations of

love, dreams, desolation, pains, suffering,

voyage and vision. Memory, dream and pain are the

time-tested triad of poets since they offer fancy

flights; time out of mind provides the

all-purpose glue to the poet to join his

thoughts. The scent of senescence and the smells

of old age is all too pervading.

"And I have

to learn afresh/The grammar of grief,/And work

out a primer of sorts/For my aged heart and

tongue."

Or,

"Old

age’s like a mongrel/Whim-pering on a wet

day,/The imagination still seeks/The skies to

soar./And thus I dangle each day/And night

between a dream/And a nightmare."

In poem after

poem he tries to be true to the title of the book

and reminds the reader that he is reading

"The Aching Vision."

"I should

have worked out/The great sum of grief./And then

a day came/A great grief ago."

Probing, the

deep dungeons of his psyche, the poet finds only

the presence of pain, suffering, grief and out

comes another bunch of poems around the same

thoughts again and again and yet again. A

birthday poem starts with this line, "I

wonder if a gift of tears/Could lift the cloud

from your heart." Another poem ends with the

words: "Yes, some pains are kingly/Generous

in thought and words."

A sort of gloom

envelops every poem.

Only once in a

while the poet comes out of this harsh reality

and harks back to dreams and memory. More than

the pain-poems the present reviewer enjoyed

reading the poems which revolve around hues and

colours of dreams — ashen dreams, silken

dreams, siren dreams, limping dreams, consoling

dreams, misbegotten dreams, etc.

"Some

dreams are killed/in the crib itself before/They

crawl out of their confines/and some remain

stricken in tracks/Pure dreams are born in a

snake-pit/And carry the poison beyond the

grave."

Even his

optimism is tinged with sadness. That happens

when one thinks only of I, me and myself.

"Carrying

the carcass of memories.../I wake up into

wonder/To see that life, withal,/was good still

and that/I could cry and laugh."

The poems in the

collection convey those moments of nostalgic

recall in dense visual accuracy. Of course, there

is fever and fret, but no delirium. Had there

been delirium, how come the poet comes out with

lines such as this one?

"There are

other aperitifs of desire/There are other drinks

of dream."

Or,

"Poems

written in cold rage/soon freeze into icicles of

pain."

Or,

"My nerves

were abused for/So long, they turned into/A slut,

and now revel/In a riot of abuse."

The poems in

"The Aching Vision" linger longer than

those in the poet’s previous collections.

"As I cast

a backward glance/On the vast spaces of my life/I

hear a pair of mocking birds/Still roosting in

their ruined nest/And flapping their ruffled

features/To set up a dynasty of dreams."

|

| |

Lopsided view of economy

Write view

by

Randeep Wadehra

Indian

Industrial Development — The Post-Reform

Scene edited by Vikram Chadha and G.S. Bhalla.

Kalyani Publishers, Ludhiana. Pages 241. Rs 250.

FOR years one of the

notable features of Indian industry has been the

reliance on the machinery and management

practices of the Industrial Revolution vintage.

Strangely, obsolescence has coexisted with

ultra-modern instruments of production and

management. Obviously, the pre-reforms industrial

scene did not seem to encourage modernisation.

It is difficult

to dismiss state investments in capital-intensive

enterprises as mere hype, as this volume would

have us believe in the preface itself. Given the

long gestation period of core sector industries

and infrastructure, the private sector was

reluctant to invest in these projects. The then

government(s) rightly stepped in. Let us not

forget that creating jobs was, and still is, an

essential government responsibility. The state

investment invariably has a multiplier effect in

boosting the economy, thus leading to the

creation of employment opportunities.

Heavy

investments in steel, road building, railways and

power generation needed and capacity commitment

that only the public sector could give. Today one

might scoff at such mega projects, but these were

essential for India’s initial industrial

progress. Privatisation of the core sector

industries might be touted as the next logical

step in our progress towards economic nirvana,

but one cannot be too sure of its success. The

rising unemployment might well become a curse if

the ongoing reforms go awry.

And what about

our small scale industries? Once upon a time, it

used to be touted as a model for quick and

certain economic growth. Now the protective

umbrella, available to it till 1990, is being

folded. The MNCs are taking over production of

items which were once reserved for the SSIs. The

downside is that this trend might obliterate the

largest private sector employer, which is also a

vital contributor to our GNP, making the already

unstable economic situation more vulnerable. On

the other hand, one might see the SSIs getting

their act together by upgrading production

technologies, using innovative management and

distribution techniques, and enhancing product

quality.

The authors

rightly conclude that the entire liberalisation

process faces numerous constraints. Foreign

investors are still tentative in committing funds

for capital-intensive projects. Infrastructure

development is uneven and grossly inadequate to

sustain a steady industrial growth. The Indian

brand is still not very popular abroad, thus

hampering exports.

There is a lot

of suspicion and cynicism vis-a-vis

liberalisation in powerful segments of economy.

One has only to listen to the Bombay Club or

trade union leaders to realise the sort of odds

that the process faces.

Contrary to

popular belief, the volume under review contends

that the liberalisation process had actually

begun in 1975. If one’s memory serves right

those were the times when the "garibi

hatao" incantation was at its loudest and

cynical worst. The authors have divided the

liberalisation process into four phases.

1. 1975-80:

delicensing of industrial units, capacity

expansion, liberalised import licensing, etc.

were introduced.

2. 1980-85: It

heralded the auto-expansion of licensed capacity,

liberalised licensing of MRTP firms, among other

things.

3.1985-90: The

Indian economy was opening up and industrial

expansion was quickening. The asset limit of the

MRTP companies was raised. More FERA and MRTP

companies were delicensed allowing wider foreign

equity participation. NRIs were offered sops for

setting up industrial units in specified areas.

4. Post-1991:

This phase is still continuing and is under

extensive as well as intensive scrutiny of

various experts and prospective investors.

This volume

consists of contributions from 26 academics

specialising in economics, commerce and

management. They teach in different universities

in India.

The chapter

"Industrial Sector: The Epicentre of

Liberalisation Syndrome" deals with the

effects of post-1991 economic policies in our

economy. The authors observe that though positive

results have yet to manifest themselves, there is

still much to be done to make the liberalisation

process effective.

One thing that a

lay person cannot help asking is how would import

of foreign consumer goods help strengthen the

economy, especially if the inflow of foreign

capital remains inadequate as compared to the

outflows of profits and dividends?

This volume is a

timely addition to the literature on new economic

theory as practised these days. Chapters on

"Industrial deregulation",

"Rationale of structural economic and

business policy changes in India", etc. can

provide useful information to students of Indian

economy.

|

| |

A different type of job

guide

Review

by M.L. Sharma

The UBS

Encyclopaedia of Careers by Jayanti Ghose. UBS

Publishers’ Distributors, New Delhi. Pages

486. Rs 250.

THESE are days of

encyclopaedias on all subjects and Jayanti Ghose

has come out with one on careers. Ghose is well

known in the media for her zeal to enlighten

readers on various vocations and her guidance has

benefited many readers. Her attempt has been to

create awareness among graduates about various

employment avenues and the relevant

qualifications.

She feels that

it is not paucity of employment avenues which is

a problem but their multiplicity. It becomes a

formidable task for a career-seeker to select one

out of dozens of careers. Hence, Ghose has

provided in the book guidance on all matters in

the professional domain.

In her

inimitable style, she guides those wanting to

enter the legal profession in the following

words: "A confidence-inspiring personality,

intelligence of a discerning nature,

perseverance, power of reasoning, patience, quick

brain, a good voice, resilience, tremendous

amount of self-confidence, some acting ability,

and creativity are the personal qualities which

can place one on the road to success in the legal

profession. Last but not the least, every legal

professional has to keep abreast of national and

international developments, various procedures,

etc. which are in the news so as to be able to

view any problem/case in real life

situations."

This tip will

stand a law student in good stead. If one is only

wishful of doing law and start practice in the

absence of these qualities, one is likely to

encounter hardships and even failure unless he or

she has a father or godfather on the Bench.

In the chapter

on MBA, she tells the aspirants about the

"need to hone their time management skills

in areas of verbal, analytical and mathematical

ability. That is in essence what the management

entrance tests evaluate. For the thousands vying

for the few seats at select management schools it

is a matter of getting selected, but the schools

focus on eliminating all but they very

best."

Brevity is the

hall-mark of this book, and her style is lucid

and makes things crystal clear. Sometimes she

uses the question- and-answer method to make

matters clear.

With regard to

the career of interior designer she observes:

"An interior designer has good placement

prospects with construction firms, firms of

architects and also in design consultancies.

Opportunities for gainful employment are

innumerable if you have the talent/training,

drive, persistence and good public relations

capability, originality and ideas that hold

appeal for the customer/client. Interior

decorators could be employed by furniture-makers,

stores selling fabric/furnishings or

manufacturers of fabric, paint/wallpaper, etc. or

those dealing in lighting equipment and

techniques." She also distinguishes the

scope of interior decorator from interior

designer.

About a career

in home science she says: "Among the more

popular services in demand are: interior design

and decoration, cooking and catering, childcare,

garden designing, beauty therapy, contract

cleaning, providing domestic and security

installation, etc. While venturing into the area

of freelance work, the primary idea should be to

keep the activity (that is) provided clear and

simple."

The preferred

skills and aptitudes for the one who wants to

enter the field of tourism are, according to her,

an enthusiastic, communicative spirit with the

ability to interact with a large variety of

people, an interest in and liking for history,

art and culture of the country. Love for the

country and interest in travelling are essential

qualities for aspirants to tourism

profession." She has given details about

work profiles too. The form of training and the

names of the specialist institutions providing

training besides career prospects are given in

the book.

There is a

complete chapter devoted to multi-media careers

like multi-media developers, visual artists,

graphic designers sound/recording specialists or

engineers, interface designers, video programmers

and editors. She has also given details about the

type of courses available and the likely

expenses. Further her information on work

environment along with work areas in all

important careers and courses enhances the value

of the book.

There are as

many as 96 chapters dealing with as many careers.

In each chapter, Ghose has provided necessary

information about the job, requisite

qualification, age, physical standards and other

conditions. Significantly, she has provided ample

guidance to job-seekers so that they can realise

whether they are fit or not. The names of

institutions and universities in India as well as

abroad providing courses in various fields are

listed. The careers dealt include that of air

traffic controller, commercial pilot,

biotechnologist, genetics and genetic engineer,

cosmetologist/beautician, social worker, plastic

engineer and technologist.

The book, neatly

printed and written in simple, clear and lucid

style, is of immense use to young job aspirants.

Ghose is a prolific writer on careers and has

been contributing articles to national dailies

and corporate journals. Her other book which UBS

has published are: "Career Guide" and

"How to Plan your Career." Actually,

this book is a revised edition of "Career

Guide".

|

| |

A big book of enduring

value

Review

by Kuldip Kalia

The Little

Book of Buddhism by His Holiness the Dalai Lama

compiled and edited by Renuka Singh. Penguin

Books, New Delhi. Pages 142. Rs 75.

LOVE and compassion, and

feeling for the sufferings and happiness of

others reveal the conscience and wisdom of the

mind,but an indifferent attitude, unscrupulous

act and unruly behaviour reflect a sick state of

the mind. But whatever the state of the mind a

person may be in, his response ultimately lies in

his or her faith in God which is firm and

universal.

The book under

review presents selected teachings of Buddhism by

the Dalai Lama. His thoughts are about the

importance of love and compassion, amplify the

multiplicity of responsibilities and elaborate

ancient wisdom. Above all, it creates awareness

of the problems of modern life. Thus his

preachings help us adopt a spiritual line and

realise the truth without any ambiguity.

Undoubtedly, the

common enemy of all religious disciplines is

"selfishness of the mind". This causes

"ignorance, anger and passions which are at

the root of all troubles of the world", he

warns. Moreover, the foundation of spiritualism

is "love". So, "if there is love,

there is hope that one may have real family, real

brotherhood, real equanimity and real

peace", the spiritual leader says. But if

this feeling is gone, others will appear and be

"enemies". In such a situation,

knowledge, education and material comfort will

not matter much and "only suffering and

sufferings will ensue".

Anyway, the

human being is bound to commit wrongs or mistakes

and whenever such a deed is done, it is essential

not to do it again. Such a resolve

"diminishes the force of all deeds".

Therefore the Dalai Lama advises: "Better to

behave well, take the responsibility for

one’s action and lead a positive life."

He says one must

learn the art of forgiveness because,

"Learning to forgive is infinitely more

useful than merely picking up a stone and

throwing it at the object of one’s anger,

especially when the provocation is extreme."

So in all situations and circumstances, we must

remain "humble, modest and without

pride." Mind you, "Discipline is a

supreme ornament."

Here are some

tips for achieving success in life.

"Determination, courage and

self-confidence" are key factors for

success. Moreover, "cultivate closeness and

warmth for others". It will help to put the

mind at case which is the "ultimate source

of success in life". He warns those who

observe that "good people suffer and evil

people enjoy success and recognition". Such

observation is "shortsighted".

It appears

strange but the harsh method for developing

patience or practising tolerance has been

suggested. The spiritual leader opines, "To

develop patience, you need someone who wilfully

hurts you. Such people give us a real opportunity

to practise tolerance."

In every case,

disciplining the mind is a must. The teachings of

the Buddha comprise three categories for this

purpose. "Shila" (training in higher

conduct); "samsadhi" (training in

higher meditation); "prajna" (training

in higher wisdom). However to understand his

teachings, one must have qualities such as,

"objectivity — which means an open

mind; intelligence — which is the critical

faculty to discern the real meaning; interests

and commitment — which means

enthusiasm".

So best suited

to individuals for the "practice of dharma"

are those who are not only "intellectually

gifted" but also have single-minded faith

and dedication". The holy man says,

"Faith reduces your pride and is the root of

veneration. With faith, you can traverse from one

stage of the spiritual to another." Further

he adds, "Faith dispels doubt and

hesitation, it liberates you from sufferings and

delivers you to the city of peace and

happiness."

There is a

caution for you. In the beginning, practice is

not easy; you need to develop a "constant,

persistent approach based on long term

commitment". At the same time, meditation is

also key to the spiritual growth because,

"mere prayer or wish will not effect inner

spiritual change; the only way for development is

by constant effort through meditation".

Then comes the

motivation. "One should practise

spirituality with a motivation similar to that of

a child absorbed in play." But the real

essence of spiritual life is your attitude

towards others. "Once you have a pure and

sincere motive, all the rest follows." And

always remember, "Every noble work is bound

to encounter problems and obstacles". Maybe,

laziness too. In his opinion, "One can be

deceived by three kinds of laziness —

laziness of indolence which is a wish to

procrastinate, laziness of inferiority, which is

doubting your capabilities, and laziness that is

attachment to negative actions or putting great

effort into non-virtue."

Never be afraid

of suffering. The holyman observes,

"Suffering increases your inner strength.

Also, wishing for suffering makes suffering

disappear". Moreover, "For discovering

one’s true inner nature, I think one should

try to take sometimes quiet relaxation, to think

inwardly and to investigate the inner

world." Ask yourself: what is attachment?

What is anger? So, "Do your best and do it

according to your own inner standard, call it

conscience."

The Dalai Lama

has summed up life when he says,"Beautiful

changes into ugliness, youth into old age, and

fault into virtue. Things do not remain the same

and nothing really exists. Thus, appearances and

emptiness exist simultaneously." Moreover,

"Whether we believe in God or karma,

everyone can pursue moral ethics."

|

| |

BOOK EXTRACT

When India’s first

regional power was born

This is an

extract from "History and Ideology" and

titled "The Punjab under Sikh rule" by

Indu Banga. The book is jointly edited by Prof

J.S. Grewal and Prof Indu Banga.

REGIONAL geography,

regional economics, regional planning and

regional politics are becoming features of our

everyday life. By now, we have reached a state of

development in historical studies when, through

deliberate pursuit of regional history, it may be

possible to concentrate on themes recurring in

different regions of the country. This may enable

us to see a pattern in diversity and get an

integrated view of the socio-political history of

India even in periods seemingly of decline and

disintegration. The regional approach, if I may

use this expression, may also help us extricate

ourselves from an empire-centred view of history

in which the Mauryan, the Mughal and the colonial

British empires are regarded as the norm. An

obvious "legacy" of British

historiography, it continues to have an appeal in

our country even after independence. However, the

cause of national integration today can perhaps

be served more effectively by a better

understanding of the phases of

"disintegration" which were marked by

the emergence of small local polities or by their

unification into regional states.

I have chosen to

discuss here the creation of a large state in

Punjab by the followers of Guru Gobind Singh in

the late 18th and early 19th century. The term

"Punjab" came into currency during the

Mughal times, although Punjabi as a literary

language for both religious and secular purposes

had been in use at least since the 13th century.

As the land of the "five rivers" Punjab

was already seen as a distinct geographical

region when Akbar constituted the province of

Lahore, largely encompassing a homogeneous

terrain, with its doabs or interfluvial

sub-regions forming the sub-divisions of the

suba. The historical and literary works of the

17th and the 18th centuries, written in and

outside Punjab, also reflect the consciousness of

Punjab as a region on the part of the ruling

class and the common people. Spatial and cultural

facets of the regional identity were reinforced

when a somewhat distinctive structure of power

brought into effect by the Khalsa emerged during

the 18th century. The numerous local polities

under dozens of Sikh Sardars as well as some

Rajputs and Pathans were unified later in the

centralised polity of Lahore under Ranjit Singh,

which was the mst powerful regional state known

to the entire history of north-western India.

This state

originated in the hectic political activity in

the wake of the decline of the Mughal power in

Punjab in the middle of the 18th century. While

the Mughal governors of Lahore were fightimg a

losing battle against the Afghans at the top, new

foci of power were emerging at the intermediate

and lower levels in the province of Lahore. The

vassals in the hills and the plains had begun

withholding tribute and contingents and making

encroachments upon their neighbours. The

zamindars and jagirdars also withheld revenues

and began to establish territorial strongholds.

However, there was no cohesion or unity of

purpose among them. The only political activity

which could be said to have had a mass base and

cohesion was that of the Sikhs. Among the Sikhs,

even the zamindars and chaudharis joined the

peasant, artisan and menial converts to the

Khalsa Panth more as their coreligionists and

less as their social leaders, and still less as

erstwhile functionaries of the government.

The struggle of

the Khalsa against the Mughal empire had in fact

started with the activities of Banda Bahadur

during 1709-15. Both in his success and fall,

Banda had provided the Sikhs with a goal and a

pattern of action. In his selection of a capital,

striking of a new coin, use of a new seal and a

new calendar, and in the appointment of his own

"governors" and other subordinate

officers, one can see an attempt to supplant the

existing government in its major details. Banda

had created a sense of shared goals and

strengthened the unity of faith which came to be

embodied in due course in the idea of "raj

karega khalsa". His fall underlined the

numerical disadvantage, tactical mistakes and

organisational limitations of the Khalsa which

they subsequently manged to overcome.

In their

struggle against the Mughal governors of Lahore

the followers of Guru Gobind Singh adopted new

organisational devices during the second quarter

of the 18th century when new military bands

called jathas and new leaders appeared on the

scene. They collectively decided matters of

offence and defence and combined the forces of

different leaders under the general direction of

one among themselves. In their periodic

gatherings at Amritsar (sarbat khalsa) they took

collective decisions (gurmatas) to combine their

fighting units into a single force (dal khalsa).

The preoccupations of the Mughal administrators

with the Afghans enabled the Khalsa to occupy

pockets of territories in the early 1750s. By the

time Ahmad Shah Abdali turned his full attention

on them in the early 1760s, it was too late. As

reported by an eyewitness, they now raged round

all the territory between the Indus and the

Sutlej and took possession of it. By 1765, they

had defeated all the nominees and allies of Ahmad

Shah in Punjab. An associate of Abdali, who had

accompanied him in his abortive expedition of

1765, regretfully observed that the Sikhs were

"fearlessly enjoying the territory from

Sarhind to the Derajat, including Multan and

Lahore." They occupied Lahore in 1765, and

struck a coin bearing the inscription that had

been used by Banda Bahadur on his seal. In this

inscription, they derived their sovereignty and

political power from God, through Guru Nanak and

Guru Gobind Singh.

The Sikhs had

conquered territory largely on the basis of the misl,

and they parcelled it out among all those who had

contributed towards its conquest. The shares thus

divided ranged from entire parganas and tappas to

groups or even fractions of villages. Those who

had led a misl or a group of misls

continued in their pre-eminence by receiving a

larger share of the conquered territory.

"Their possessions could develop into

sovereign states because of territorial

contiguity over an area that was economically

viable and politically capable of defence."

Recruitment of personal armies (khas fauj)

and hereditary succession along with individual

initiative led to the emergence of nearly three

scores of small or large centres of power under

minor or major rulers, each jealously guarding

his independence and possessions and trying to

encroach upon his neighbours and old associates.

Ranjit Singh

emerged as the pre-eminent ruler of Punjab out of

this struggle for territories and power. During

the first two decades of the 19th century, the

small states largely under the Sikhs and spread

over the upper doabs came under Ranjit

Singh’s control. His dominion vastly

expanded with the conquest of the Afghan

strongholds of Multan and Kashmir, and the

subjugation of the Rajput principalities in

Punjab hills. The tribal territories across the

river Indus were subjugated in the 1820s and

annexed in the 1830s. Ranjit Singh died in 1839,

and his successors lost the kingdom of Lahore to

the British finally in 1849. The core of this

state consisted of the upper doabs which had

remained under sovereign Sikh rule for the

longest period, from 1765 to 1845, and which had

also formed the core of the Mughal province of

Lahore. Besides his military reforms and

diplomatic efforts, Ranjit Singh had been helped

in the creation of a large state by the friendly

indifference of the British who had reached the

Sutlej at the beginning of his rule. However, in

the organisation of the state, Ranjit Singh

looked up to his Mughal predecessors, referring

to them as shahan-i-qadim, and to Mughal

rule as qarar-i-qadim and reviving its

political and administrative institutions as far

as possible. In this he followed his Sikh

predecessors.

The political

organisation of the new state was marked by

accommodation and conciliation. The existence of

numerous centres of power in the region, the

tradition of autonomy in the hills and the

north-west, and the limited resources of the new

rulers obliged them to continue with the

institution of vassalage. This arrangement

enabled them to combine external political

control with internal autonomy, and ensure, among

other things, the payment of tribute. The rulers

of the 18th century used vassalage in the limited

area and on a smaller scale. Under Ranjit Singh

it encompassed the Sikh, the Rajput and the

Pathan chiefs in all the major sub-regions of the

kingdom of Lahore. This tradition was so strong

in the hills that Ranjit Singh even created new

rajas. The essential features of suzerain-vassal

relationship under him were largely those that

had been institutionalised by Akbar, but their

application varied according to the local

circumstances and distance from the seat of

authority. At the same time, vassalage remained

essentially a transitional arrangement, and by

the end of his reign, Ranjit Singh had subverted

more than half of the traditional tribute-paying

areas, thus effecting on the whole greater

intra-regional integration.

The territorial

organisation of the new state was related to its

political development. The possessions or

talluqas of the early Sikh rulers and others were

basic blocks of varying sizes that were

incorporated later, either all at once or in

parts, into the kingdom of Lahore.

Ranjit Singh

tried gradually to integrate them into a broad

pattern of territorial organisation, at the

primary, secondary and tertiary levels,

corresponding to the suba, the talluqa and the

tappa. New primary units were created through a

process of piecemeal conquest and improvisation.

The former Mughal province of Lahore was broken

up into half a dozen primary divisions. Elsewhere

also, with the exception of the province of

Kashmir which was conquered all at one time, and

partly of Multan, each province was

"comparable to an average sarkar of the

Mughal times." (Ranjit Singh retained the

earlier fragmentation of the parganas and the

talluqas of his predecessors, which now became

the effective administrative sub-division next to

the suba. The average size of his secondary

division was much smaller than the size of an

average Mughal parganas.) Thus, the number of

secondary as well as primary units increased. At

the level of the tertiary division of the tappa,

however, the attempt on the whole was to revert

to the long established local sub-divisions as

they generally conformed to the clan composition

in a locality.

The

administrative arrangements evolved with time. An

average ruler in the late 18th century had a

diwan at the headquarters who maintained records

of revenue collection and kept accounts. In the

territorial sub-divisions of varying sizes, there

was generally the kardar, occasionally called the

amil or the tehsildar, who primarily supervised

the collection of revenues and maintained peace

and order in the area. The local hereditary

officials—chaudharis and

qanungos—continued to serve the state by

assisting the kardars. In the village, the

muqaddams and patwaris continued performing their

traditional functions. The fort-towns were

garrisoned by qiladars or thanadars who saw to

the defence and expansion of the Sardar’s

territories. They also helped in the maintenance

of law and order. The state functionaries usually

combined several functions. The kardar seems to

have exercised some judicial authority but the

core of the judicial arrangements of the new

states consisted of the village, the caste or

clan panchayats, in addition to the hereditary

qazi whose office had been kept up by the new

rulers.

In the kingdom

of Lahore administration was organised on a much

bigger scale. The nazim was appointed to the suba

and the kardar to the talluqa, while the chaudhri

looked after the tappa or its equivalent unit.

All of them were concerned with the collection of

revenues, promotion of cultivation, maintenance

or order and suppression of crime. The qazis in

towns and the adaltis or mobile judges in the

countryside also administered justice. The degree

of control over the administrative personnel

varied with their distance from the seat of

government and the local circumstances, according

to which varying degrees of autonomy was

permitted to them. The attempt on the whole was

to make as little change as possible in the

existing administrative structure and practices

at the local level. The new state thus retained

the sub-regional diversities coming down from the

Mughal times. This was particularly true of the

land revenue administration, with perhaps the

difference that the "state favoured all

those who were prepared to keep the land under

cultivation and pay the revenues, irrespective of

their right or caste or tribe."

Military

organisation was the only sphere in which Ranjit

Singh made a deliberate attempt to change and

innovate. He was obviously aware of the

importance of the western military system against

traditional armies. Around 1800 AD he had a force

of about 5,000 cavalrymen using matchlocks. By

the end of his reign, he had a one lakh-strong

army, a sizeable part of which consisted of

trained artillery backed by infantry battalions.

Area for area, this was probably the most

powerful army known to Asia. By assimilating his

military organisation to the European system and

his administrative organisation to the Mughal,

Ranjit Singh was probably trying to adjust to the

contradictory pulls of the historical situation

in which he was placed.

The extensive

use of the institution of jagirdari in the new

state reflected the force of historical

circumstances. There was scarcely a Sikh who was

not a jagirdar Nearly half the civic and military

functionarties of the kingdom of Lahore were paid

through jagirs. There was in fact a close

relationship between the process of the creation

of state and the institution of jagirdari. It

became the means of maintaining an armed force

and rewarding the partners in conquest. It freed

the emergent ruler from the obligation of making

large sums of cash available and also gave a

stake to the assignee in defending his own jagir

as well as the territories of the ruler.

Moreover, the social prestige attached to the

institution of jagirdari made it easier for the

dispossessed ruling class to get reconciled to

their loss of power in return for jagir for

service or subsistence.

The new ruling

class under Ranjit Singh consisted largely of

Sikh Jats, Khatris and Brahmins, besides some

Sayyids, Pathans and Europeans. Members of the

ruling class "shared overwhelmingly in the

distribution of the resources of the state"

as ministers, courtiers, provincial governors and

commanders. At the secondary level of the power

structure, however, members of the local

aristocracy, who were largely Muslim, continued

receiving jagirs or revenue free land as

chaudharis, muqaddams, qanungos and qazis. Many

of them were also inducted into the government as

kardars or as officers in the army. The new state

thus sought to perpetuate itself by accommodating

the existing vested interests, and by creating

new ones.

Religious

grantees represented an important category of

vested interests that served the state as

"social links with thr conquered

territory." The general policy of Ranjit

Singh, as also of his Sikh predecessors, was to

confirm existing grants and make fresh ones to

members of all faiths. Consequently, a large

number of khanqahs, masjids, Vaishnava and Shaiva

establishments as well as Brahmins, Sayyids,

Shaikhs and pirzadas not only continued in their

privileges coming down from the Mughal times, but

also received fresh grants of revenues or cash.

Individuals and institutions belonging to the

Sikh faith—Udasis, Nirmalas, Bhais,

Granthis, Ragis, and descendants of the Gurus as

well as gurdwaras—received the largest

amount of fresh dharmarth grants during

this period, amounting nearly to half of the

total revenues alienated in charity.

Charitable

grants of Ranjit Singh and other Sikh rulers were

an expression as much of their sense of piety and

catholic outlook as of their awareness of their

historical and regional context. The ideology of

raj karega khalsa, which had pulled the Sikhs

through a crisis and led to the establishment of

their rule, was likely to be awkward and

dangerous for its stability. By identifying

themselves fully with the Khalsa Panth, and by

liberally patrionising the religious groups

representing Sikh orthodoxy, the Sikh rulers were

in fact trying to contain the ideology of raj

karega khalsa. Furthermore, placed in a region

with an overwhelmingly non-sikh population, more

than 90 per cent of the total, the Sikh rulers

had to consciously secularise their rule by

extending patronage to their non-sikh subjects,

and by allowing them to share power and

privileges with the Sikhs. However, the principle

that underlay the functioning of the state under

Ranjit Singh was that "no one, not even the

princes and the collaterals or the most

influential of the sardars or the most pious of

the dharmarth grantees, could retain a piece of

land or settle a dispute without reference to the

sovereign."

Despite

"structural and functional continuity"

from the Mughal times, the new ruling class in

Punjab came to have a sizeable component from

amongst the social groups that were a relatively

able component from amongst the social groups

that were relatively low in the social hierarchy

in the early 18th century. Historical

developments of the period had been affected by

the Sikh movement which did not normatively

recognise any hereditary barriers to upward

mobility and even encouraged individual

achievement. An environment conducive to greater

openness of society was also conducive to

secularisation of politics. The factional

alignments of the members of the ruling class

under Ranjit Singh and his successors cut across

communal and racial affiliations. They fought for

power and wealth as individuals and against the

British as Punjabis.

In fact,

increased identification with the state and

heightened consciousness of a Punjab identity are

evident during this period. The regional identity

had been evolving for quite some time. The ruling

classes of Punjab had developed this

consciousness before the establishment of Sikh

rule; the people at large developed it under

Ranjit Singh. Besides the ties of language and

culture among an overwhelming majority of the

ruling class, the presence of hostile neighbours

virtually throughout the period of Sikh rule

dictated solidarity between the nobility and the

rulers in the self-interest of both. Thus, as

reflected in the contemporary Punjabi literature,

a popular movement and the interests of the

ruling class had coalesced into a

well-articulated regional sentiment by the end of

Ranjit Singh’s reign. This regional

sentiment tended to transcend communal

differences, making for cultural coexistence.

After the subversion of this regional kingdom,

the poet Shah Muhammad regretfully referred to

the British as "third community" to

enter the region where the Hindus and the Muslims

had long lived in peace and prosperity.

|

| |

REJOINDER

A

book is for reading

Surjit

Hans writes from Patiala

I THANK Prof

Bhupinder Singh for the courtesy of going through

my review of "Terrorism in Punjab" by

Puri, Judge and Sekhon. I wish he had extended a

similar courtesy to the authors of the book by

having a first-hand knowledge of their work. To

depend on second hand information — that is,

a review — however reliable or unreliable,

is excusable in an undergraduate but it is not

the done thing among reputable scholars.

His citing of

Guru Hargobind enlisting the rejects of society

is regrettable. Religion makes saints of sinners,

it does not stop at enlisting them.

I am sure Prof

Bhupinder Singh would not think it

uncomplimentary if I say that he has avidly

demonstrated in his write-up that he is a huge

consumer of knowledge, not its producer like

Puri, Judge and Sekhon. The loss is ours more

than his.

|

|