|

Mallika on a

mission

Aditi Tandon

Her beauty, her

IIM degree, her bindaas attitude and the Sarabhai suffix to her

name emerge as mere incidentals when you shake hands with

Mallika Sarabhai, the theatre artiste and activist who is out to

set many social wrongs right.

|

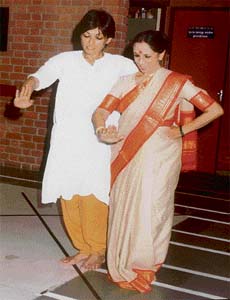

HER MOTHERíS DAUGHTER: Mallika finetunes her dance with her mother Mrinalini Sarabhai

|

HER

dense, long mane is history. So is her once-raging reputation as

a sex symbol. Mallika Sarabhai, today, is a woman reinvented,

and liberated from the shadows of her past. Crisp, short hair is

just part of the makeover for this artiste, who is now

centrestage with her activism.Not too long ago, she was seen

wooing a handsome Farooque Shaikh in the all-time film Katha.

That was, obviously, not the kind of job to have engaged a rebel

for long. Mallika was destined to move on, and she did`85

towards new horizons. Not that she was ever afraid of setting

out new journeys. That, after all, was the family tradition and

business. At a time when classical dance was still considered

sacredly traditional, her mother Mrinalini Sarabhai was

modifying Bharatanatyam to create a contemporary dance idiom. At

another end, her aunt Lakshmi Sahgal was commanding the Indian

National Army. And then there was the celebrated family

history to fall back on ó her great aunt Amulya Sarabhai

headed the great Textile and Labour Association strike, the

first labour union strike of India. The agitation saw Mahatma

Gandhi negotiating with the management, on behalf of the

workers, and the results were heartening. The labourersí got a

half paisa raise in their salary; and Gandhi another affirmation

in the power of peaceful negotiation. A young Mallika was,

thus, naturally trained to dare and explore, not so much by

virtue of her motherís artistic trespasses as due to her

father Vikram Sarabhaiís resoluteness that placed India on the

worldís nuclear map. Today, in Gujarat where she lives,

political masters mention her with a pinch of salt. She, after

all, bared the wounds that Godhra left, and dragged the state

Chief Minister Narendra Modi to court. Whatís more, she got

from the court a direction that cases ordered closed by the

Gujarat police be reopened and victimsí claims of compensation

be examined afresh. Dancer with a voice Come to

think of it Ė sheís just a dancer. But one who has found her

voice, a voice thatís strong enough not to be silenced. Not

even by the bombs extremists throw at Darpana, Mallikaís

academy of performing arts in Ahmedabad, which has become a

symbol of her activism. From Darpanaís compounds, Mallika has

initiated a chain reaction of change. And in effecting change,

art has been her first tool, management her second. The

sequence was the reverse when Mallika was still on the threshold

of her career. Urged by her father, she went to IIM, Ahmedabad,

even when he was no longer alive to see her through the

competition. "I wanted to be a demographer, but papa wanted

me to take management training so that together we could build

great institutions for India, institutions that could run

without considerations of profit. He died in 1971. I remember

taking the IIM test a day after I cremated him," Mallika

says, with pride. The next thing she remembers is that she was

in, filled with a desire to do new things. Her chance came when

David Mc Leyland, the Harvard professor who was christened the

founder of the motivational theory, agreed to guide her PhD on a

topic that was way ahead of its times. "I wanted to study

how to develop structures that could foster creativity. But a

more important part of my research was the study of power motive

in India, which has always revered those who have renounced

power," says Mallika who, through her research, proved that

only a fraction of the society was, eventually, interested in

working without the expectation of reward. "My study

proved that at 11 years, 90 per cent of the people believed

there was a direct relation between input and output; the number

had dropped to 40 per cent by 15 years and just 10 per cent by

19 years. This 10 per cent was made up of students, whose

parents had not lied to them about society and its evils. They

had been forewarned of the all-pervasive rut and they were ready

for it," Mallika reasons, explaining how she applied

management training to Darpana, which gets no government or

corporate funding. "I donít think I could have ever run

Darpana if I didnít have my degree," she says. As the

range of conversation widens, Mallika makes another interesting

confession: "As a child, I had deep love for theatre and

puppetry. I never really wanted to dance. I was just too lazy or

perhaps afraid that I lacked the commitment my mother had for

dance. I learned dance only because others in the class were

learning." Love for theatre Her inclinations,

however, were going to change. In 1977, Mallika gave her first

performance as a dancer. A French government award followed.

Soon, she was being hailed as the prefect protagonist for her

motherís choreography. "I never thought I could create,

until Peter Brookís Mahabharata happened in 1980,"

Mallika had portrayed the character of Draupadi in the 12-hour

theatrical, which was later made into a movie. To Mallika,

Drapuadi remains the perfect feminist: "She is the only

woman in our mythology whom men could not reduce to a goddess

because she was just so strong. They could not limit her to the

altar. She was courageous enough to tell Yudhishthira Ė `You

may be a great man, but youíre a weak maní. I respect her

for that." Draupadiís role brought Mallika closer to her

real self: "I realised that the best language for activism

was artistic expression. With this language, I could engage with

everything I ever wanted to. I started telling social realities

through dance theatre. Gradually, I found global partners in the

campaign for human rights." Mallikaís first dance

theatre production Shakti: The Power of Woman became a

rage in art circles. With Shakti, she had arrived on the

contemporary Indian dance scene. Her ability to write her own

works, transcend tradition and employ idioms like martial arts

to project human longing lent her the edge that still sets her

apart. As co-director of Darpana, founded by her mother in 1949,

she went on to fashion several productions, while managing the

academyís other wings, including development, folk/tribal art,

centre for non-violence through arts and conservatory. Her skill

lay not just in her mastery over dance forms, but also in her

ability to adapt the realities of gender-based violence for

theatrical presentation. Exploring Hinduism The

finest specimen of Mallikaís talents remains Sitaís

Daughters, her most celebrated production, performed across

40 countries, in three languages. The piece engages with issues

like female foeticide and domestic violence and inspires women

to "never give in". In Search of the Goddess is

another striking theatrical which Mallika uses to explore

Hinduism and womenís role therein. Itís this understanding

that leads to her conflicts with radicals, who fear her for what

she is. "Itís fine if Modi has problems with me. I donít

require a stamp of good housekeeping from him. I have a strong

moral code thatís my own and I will live by it. I have always

done things without hiding them," says Mallika, remembering

her college days, which saw her wearing mini-skirts, dating men,

even going in for a live-in relationship. She finally married

and then divorced Bipin Shah, with whom she now runs Mapin

Publishing. "We share a great friendship now, although we

had an unhappy divorce. I was actually talking about my divorce

so that everyone could learn from it," says Mallika, fire

rising in her eyes as she continued talking of Hinduism and

bigotry. "Seventy per cent of the sex workers in Gujarat

are such whose husbands are pimps, but the radicals have a

problem talking about sex. They have ended up "Talibanising"

Hinduism by ignoring its basic tenets. The religion directs us

to never accept anything without questioning; these people donít

let you question. The religion preaches Vasudhaiv Kutumbhkam.

I know no other way of living but by taking them on,"

says Mallika, the activist, who has paid a heavy price for

speaking her mind. For the marginalised Sheís,

perhaps, the only woman artiste in the country who has never

been honoured by her government, although she has countless

"foreign" awards. "When I went public with my

anti-Modi stand post-Godhra, I lost every single friend in town.

I also lost corporate funding for Darpana. Now, every single

penny that I earn goes into running the institution. This is one

area where I feel my surname has gone against me. People canít

believe a Sarabhai being short of funds," she laughs,

admitting that she has been a maverick, who had raised her

children on the diet of reality, no matter how

harsh. "This society stinks more than ever before and I

have told my children that it stinks. Itís for us to warn them

that times need change. My latest work, Unsuni, based on

Harsh Manderís book Unheard Voices is about these

realities, which I have showcased to enable change. The stories

celebrate the spirit of five real people ó one of them a woman

who has spent a lifetime carrying human waste on her shoulders.

If not anything else, we owe her our attention. Incidentally,

the government tried to censor Unsuni," Mallika

gloats, mentioning also of the Unsuni voluntary movement, which

seeks support for the marginalised. Next from her repertory

will be Swakranti and Colours of the Heart. The

first (literally meaning a revolution within) is a reflection of

Mallikaís Gandhian beliefs; the second is a reaction to her

encounters with people with extreme views. But topmost on

her mind is something she calls "voluntary action through

art", a new mission in which she finds her son Revanta and

daughter Anahita, by her side. Both, like her, are generously

endowed with traits that are typically Sarabhai.

|