|

Fictional worlds

Rumina Sethi

SOMEHOW the year 2009 did not seem

remarkable for fiction (or perhaps I fell into a black hole). The

previous year was marked by a literary explosion: Salman Rushdie’s The

Enchantress of Florence burst upon the scene in its first quarter;

Amitav Ghosh’s Sea of Poppies followed in the summer.

Interspersted between these literary giants was an excellent

collection of short stories by Jhumpa Lahiri, Unaccustomed Earth.

Such literary ancestry, understandably, is hard to chase. But for the

London Book Fair, at any rate, it was the year of the Indian novel. In

one sense it is, as the young debutante elbows out the old,

established brigade. SOMEHOW the year 2009 did not seem

remarkable for fiction (or perhaps I fell into a black hole). The

previous year was marked by a literary explosion: Salman Rushdie’s The

Enchantress of Florence burst upon the scene in its first quarter;

Amitav Ghosh’s Sea of Poppies followed in the summer.

Interspersted between these literary giants was an excellent

collection of short stories by Jhumpa Lahiri, Unaccustomed Earth.

Such literary ancestry, understandably, is hard to chase. But for the

London Book Fair, at any rate, it was the year of the Indian novel. In

one sense it is, as the young debutante elbows out the old,

established brigade.Tabulating novels, in any case, is difficult

when the time-space is limited to one year. If one were to categorise

novels read in a lifetime, it would make the exercise much simpler. In

one particular year, for instance, one may not have discovered writing

in regional languages or it may not be a productive year for a

particular language writer. Then again, certain writers gain

prominence less for literary quality than for circumstantial

expediency. Vikas Swarup was talked about more in 2009 than the year

in which he published Q and A as its celluloid version

Slumdog Millionaire collected its Oscars. Chetan Mehta, in the

meanwhile, gathered more fans as every graduate student who passed his

postgraduation entrance test quoted Two States: The Story of My

Marriage as his "favourite book". Neither of them,

however, are blue-blooded literary figures who can rub shoulders with

those who write "literature" as we know it.  In the world of

Indian English writing, which is more or less my linguistic field (and

limitation), literary watchers would perhaps cite Chandrahas Chaudhury’s

Arzee the Dwarf among one of India’s surprises. A delightful

debut novel that combines exceptional art with a great story, it

traverses the diversity of Bombay with as much aplomb as Midnight’s

Children or Slumdog giving it something of a cosmopolitan

colouring without straining overmuch for effects. Arzee, a

projectionist at a local cinema, has a "small frame" but a

"big imagination" who moodily maps out his version of Bombay

when he loses his job and unwittingly absorbs us into his world of

exaggerated chaos. Chaudhury is a master of understatement and

suggestion which works to his great advantage. In the world of

Indian English writing, which is more or less my linguistic field (and

limitation), literary watchers would perhaps cite Chandrahas Chaudhury’s

Arzee the Dwarf among one of India’s surprises. A delightful

debut novel that combines exceptional art with a great story, it

traverses the diversity of Bombay with as much aplomb as Midnight’s

Children or Slumdog giving it something of a cosmopolitan

colouring without straining overmuch for effects. Arzee, a

projectionist at a local cinema, has a "small frame" but a

"big imagination" who moodily maps out his version of Bombay

when he loses his job and unwittingly absorbs us into his world of

exaggerated chaos. Chaudhury is a master of understatement and

suggestion which works to his great advantage.

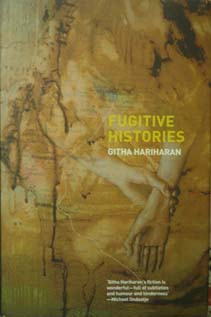

Gita Hariharan’s

much darker novel, Fugitive Histories, is a narrative which

weaves through images retrieved from memory. This is a political

novel, in that the central episode is the Godhra carnage and its

assortment of horrors. The novel is slow-paced and one has to wait

expectantly for the plot to tighten, for details to affect one’s

imagination. Hariharan has a formidable reputation but, on the whole,

I am a little ambiguous whether to shower praises or to admit candidly

that the composition did not work for me. I can surely recommend one

engaging book by a writer I have often reviewed—Timeri Murari’s The

Imperial Agent—which was republished this year, that traces the

future life of Rudyard Kipling’s Kim as he grows older and becomes a

British secret agent. Kim has to grapple with his two identities—Indian

and British—and make the difficult choice within the "ambiguity

of belonging". From national themes to romance, Murari depicts

British India in all its dulled glamour and departed strength.   And

what of the writers of South Asia some of whom grabbed a slice in the

literary market this year? For fans of dystopic fiction, Like a

Diamond in the Sky, by the Bangladeshi novelist Shazia Omar, is

buzz-worthy. Here is an intense novel about the changing landscape of

the tortured mind of a drug addict whose addiction is an escape from

the harsh realities of the world of which both he and the new nation

are victims. The khor (or junkie) in this novel gave a spurt to

my inadequate linguistic range in the subject as I came across an

addict’s vocabulary of "pethidine", "turquing"

and "craving a chase". Side by side, though, Omar paints the

political climate of Bangladesh that was "born of the hopes and

dreams of idealistic people who wanted freedom and democracy"

that unfortunately "gave way to unbridled corruption".

Another Penguin book of short stories from Pakistan, Do You Suppose

it’s the East Wind? translated from Urdu by Mubammad Umar Memon

is a significant addition to the existing literature on Pakistan. Many

writers of this collection have been born in pre-Partition India and

migrated to the other side in 1947. True to experience, the stories

are about well-meaning Pakistanis involved "in the act of

living" with the intention of nullifying the focus on

fundamentalism that has become such an essential(ised) part of

Pakistani identity. Ali Sethi’s The Wish Maker could join

this list if it had not been so full of colourful cultural clich`E9s

and swear words of the subcontinent. And

what of the writers of South Asia some of whom grabbed a slice in the

literary market this year? For fans of dystopic fiction, Like a

Diamond in the Sky, by the Bangladeshi novelist Shazia Omar, is

buzz-worthy. Here is an intense novel about the changing landscape of

the tortured mind of a drug addict whose addiction is an escape from

the harsh realities of the world of which both he and the new nation

are victims. The khor (or junkie) in this novel gave a spurt to

my inadequate linguistic range in the subject as I came across an

addict’s vocabulary of "pethidine", "turquing"

and "craving a chase". Side by side, though, Omar paints the

political climate of Bangladesh that was "born of the hopes and

dreams of idealistic people who wanted freedom and democracy"

that unfortunately "gave way to unbridled corruption".

Another Penguin book of short stories from Pakistan, Do You Suppose

it’s the East Wind? translated from Urdu by Mubammad Umar Memon

is a significant addition to the existing literature on Pakistan. Many

writers of this collection have been born in pre-Partition India and

migrated to the other side in 1947. True to experience, the stories

are about well-meaning Pakistanis involved "in the act of

living" with the intention of nullifying the focus on

fundamentalism that has become such an essential(ised) part of

Pakistani identity. Ali Sethi’s The Wish Maker could join

this list if it had not been so full of colourful cultural clich`E9s

and swear words of the subcontinent.

Orhan Pamuk’s new novel, The

Museum of Innocence, is also a symphonic reading experience; it

takes us from an elitist social world with its trappings of opulent

parties, clubs and society gossip to the backstreets of Istanbul. This

is a veritable museum of love and guilt, of hopes and shame, a

reservoir of the inherent characteristics of Istanbul society. I

cannot close without a mention of J. M. Coetzee’s novel, Summertime.

As this is the last of his memoirs, he turns out as the central

character, but dies on page 15 leaving the rest of the pages to be

filled by a series of his friends and relatives who give interviews

and accounts of their association with the author. The various

"characters" reminisce a great deal about Coetzee’s

relationship with his father, their moments of bickering and

conviviality as much as about South Africa, Coetzee’s native land,

and apartheid. What stands out most is the self-effacing style of the

novelist who is gutsy enough to pen down the following description of

himself as narrated by a woman-academic he had a brief affair with:

"As a writer he knew what he was doing, he had a certain style,

and style is the beginning of distinction. But he had no special

sensitivity that I could detect, no original insight into the human

condition. He was just a man, a man of his time, talented, maybe even

gifted, but, frankly, not a giant." Orhan Pamuk’s new novel, The

Museum of Innocence, is also a symphonic reading experience; it

takes us from an elitist social world with its trappings of opulent

parties, clubs and society gossip to the backstreets of Istanbul. This

is a veritable museum of love and guilt, of hopes and shame, a

reservoir of the inherent characteristics of Istanbul society. I

cannot close without a mention of J. M. Coetzee’s novel, Summertime.

As this is the last of his memoirs, he turns out as the central

character, but dies on page 15 leaving the rest of the pages to be

filled by a series of his friends and relatives who give interviews

and accounts of their association with the author. The various

"characters" reminisce a great deal about Coetzee’s

relationship with his father, their moments of bickering and

conviviality as much as about South Africa, Coetzee’s native land,

and apartheid. What stands out most is the self-effacing style of the

novelist who is gutsy enough to pen down the following description of

himself as narrated by a woman-academic he had a brief affair with:

"As a writer he knew what he was doing, he had a certain style,

and style is the beginning of distinction. But he had no special

sensitivity that I could detect, no original insight into the human

condition. He was just a man, a man of his time, talented, maybe even

gifted, but, frankly, not a giant."

End-of-the-year wrap-ups,

as I said, are not easy. Many books get left out and there is always

the risk of having to go with somebody else’s criteria. But who

knows, the list could give you solace and warmth in the winter months.

|