|

Sense of deja vu, all over again

Reviewed by Khushwant S. Gill

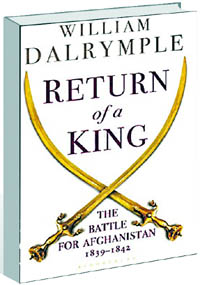

Return of a King: The Battle for Afghanistan 1839-1842

By William Dalrymple

Bloomsbury. Pages 567. Rs 799

The

Afghan dilemma never seems to end. Armies and nations come and go but

the endless cycle of violence, death and destruction flows on. For a

beautiful land and it's people this is a continual tragedy on a

monumental scale. Celebrated writer and historian William Dalrymple

strums this cord perfectly as he unfolds a captivating tale of

19th-century imperial intrigue, human ambition, bravery, treachery,

incompetence and hubris. The

Afghan dilemma never seems to end. Armies and nations come and go but

the endless cycle of violence, death and destruction flows on. For a

beautiful land and it's people this is a continual tragedy on a

monumental scale. Celebrated writer and historian William Dalrymple

strums this cord perfectly as he unfolds a captivating tale of

19th-century imperial intrigue, human ambition, bravery, treachery,

incompetence and hubris.

At one level, the

book follows the fortunes of Shah Shuja, the deposed king of

Afghanistan who, instead of giving up and languishing in exile,

persistently tries to regain the throne of Afghanistan with British

help. Set against this backdrop, Dalrymple's book brilliantly weaves

in many other colourful threads and characters that made the history

of this period so unsettled and exciting — the uneasy relationship

between the East India Company and Ranjit Singh's Sikh kingdom; the

Great Game between Russia and Britain for control of Afghanistan and

South Asia; the crystallisation of the modern Afghan state from a

loose, often-changing, confederation of city-based states extending

into Central Asia and referred to as Khorasan; and the intersecting

rivalries, connections and nature of the Afghan tribal structure.

The

last element, still misunderstood and either overly romanticised or

reviled, is of relevance to the 21st century. He proposes that the

ill-conceived British invasion of Afghanistan in 1839 has it's

parallels to the more recent Russian and US invasions and further

emphasises the near impossibility of imposing an "outside"

solution to the Afghan problem. True in some aspects, it is an

overstatement. The 2001 invasion was a hunt for Bin Laden and Al-Qaida

and by extension the destruction of their hosts, the Taliban. Ridding

a nation of a terrorist organisation and it's infrastructure is no

easy job and only the billions of dollars spent each year by having

boots on the ground has accomplished this task. The Taliban are still

around, but they never were the primary target. Despite drawing this

oversimplified parallel between 1839 and 2001, Dalrymple has produced

a highly enjoyable and informative read. Down the ages Afghanistan's

problems have usually not originated within itself but come from

outside — be it international intrigue and power play or foreign

terror organisations staking out the mountainous nation. As a young

British captain scribbles in his diary in 1838 before setting off for

the First Afghan War, "We are on the verge of something

momentous. They say we are going to fight the Russians or

Persians." The

last element, still misunderstood and either overly romanticised or

reviled, is of relevance to the 21st century. He proposes that the

ill-conceived British invasion of Afghanistan in 1839 has it's

parallels to the more recent Russian and US invasions and further

emphasises the near impossibility of imposing an "outside"

solution to the Afghan problem. True in some aspects, it is an

overstatement. The 2001 invasion was a hunt for Bin Laden and Al-Qaida

and by extension the destruction of their hosts, the Taliban. Ridding

a nation of a terrorist organisation and it's infrastructure is no

easy job and only the billions of dollars spent each year by having

boots on the ground has accomplished this task. The Taliban are still

around, but they never were the primary target. Despite drawing this

oversimplified parallel between 1839 and 2001, Dalrymple has produced

a highly enjoyable and informative read. Down the ages Afghanistan's

problems have usually not originated within itself but come from

outside — be it international intrigue and power play or foreign

terror organisations staking out the mountainous nation. As a young

British captain scribbles in his diary in 1838 before setting off for

the First Afghan War, "We are on the verge of something

momentous. They say we are going to fight the Russians or

Persians."

Writing in a lucid,

sweeping style and drawing upon Western, Indian and Afghan sources,

Dalrymple makes good use of the dramatic events of the First Afghan

War to highlight this cyclical obsession with and desertion of

Afghanistan. In the process, he spins a historical yarn that borders

on fiction in it's readability.

|