|

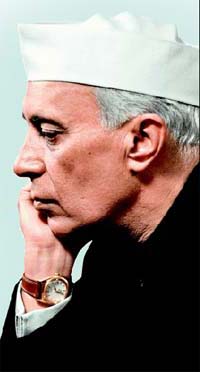

India through Nehruís eyes India through Nehruís eyes

Reviewed by M Rajiv Lochan

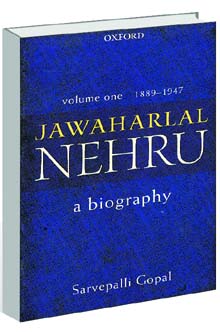

Jawaharlal Nehru, A Biography, Vol 1 1889-1947

by S. Gopal, Oxford University Press,

New Delhi.

In

this monumental biography of Nehru his biographer, Gopal, shows us the

story of India through Nehruís eyes as it were. Gopal begins by

telling about the strategies of the British to win allies in India so

that there was always someone who was willing to support the unbroken

monopoly over power established by the East India Company. In the

process, grandees with loud-sounding titles were created. Rulers of

Indian riyasats, many of them as small as a handful of villages

and all of them tyrannical towards their people, were elevated to the

rank of "Counsellors to the Empress". Uneducated young men

of high birth were made low-level civil servants to help maintain

English control over India. Under these circumstances, self-made men

like Motilal Nehru, even when eager to please the English, found

English rule reprehensible. When his much-pampered son, Jawaharlal,

introduced Motilal to another world Ė one in which Gandhi was

questioning the right of the English to ruleóMotilal eagerly joined

in and encouraged Jawaharlal to focus on getting rid of the English

rather than be bothered about earning a living. In

this monumental biography of Nehru his biographer, Gopal, shows us the

story of India through Nehruís eyes as it were. Gopal begins by

telling about the strategies of the British to win allies in India so

that there was always someone who was willing to support the unbroken

monopoly over power established by the East India Company. In the

process, grandees with loud-sounding titles were created. Rulers of

Indian riyasats, many of them as small as a handful of villages

and all of them tyrannical towards their people, were elevated to the

rank of "Counsellors to the Empress". Uneducated young men

of high birth were made low-level civil servants to help maintain

English control over India. Under these circumstances, self-made men

like Motilal Nehru, even when eager to please the English, found

English rule reprehensible. When his much-pampered son, Jawaharlal,

introduced Motilal to another world Ė one in which Gandhi was

questioning the right of the English to ruleóMotilal eagerly joined

in and encouraged Jawaharlal to focus on getting rid of the English

rather than be bothered about earning a living.

Gopal tells the story of

Jawaharlal with great sensitivity. In this, he is considerably helped

by Jawaharlal who maintained detailed records for himself and left

extensive notes on any and everything. Many of the jottings of Nehru

were designed to be published and became bestselling books of their

times. At the height of his popularity, Nehru even managed to publish

an obituary for himself some three decades before his death warning

people of being too warm to a "populist leader like Nehru".

Drawing upon newspapers,

government records, the writing and speeches of Jawaharlal and the Nehru

Papers, Gopal draws out the dilemmas of the times in which Motilal

lived. Motilal, he tells us, would have been one of the few persons

who refused to do penance after his return from England. Gandhi, one

might add, did. Motilal had even dropped his caste name, Kaul, in

favour of Nehru, a non-caste specific word. Jawaharlal was brought up

in a household that did not much follow the evil traditions of India.

Yet, in public life, both father and sons had to face the ignominy of

being addressed as "Pandit" by an adoring public. For those

who keep wondering whether Nehru benefited from being the son of his

father and being close to Gandhi, Gopal details the administrative

experience that young Nehru got contesting municipal elections.

Elected Chairman of the Allahabad Municipal Board, he was quick to

realise the possibilities and impossibilities that mark the running of

an administration in contrast to merely spouting political opposition

to the existing administration. Drawing upon newspapers,

government records, the writing and speeches of Jawaharlal and the Nehru

Papers, Gopal draws out the dilemmas of the times in which Motilal

lived. Motilal, he tells us, would have been one of the few persons

who refused to do penance after his return from England. Gandhi, one

might add, did. Motilal had even dropped his caste name, Kaul, in

favour of Nehru, a non-caste specific word. Jawaharlal was brought up

in a household that did not much follow the evil traditions of India.

Yet, in public life, both father and sons had to face the ignominy of

being addressed as "Pandit" by an adoring public. For those

who keep wondering whether Nehru benefited from being the son of his

father and being close to Gandhi, Gopal details the administrative

experience that young Nehru got contesting municipal elections.

Elected Chairman of the Allahabad Municipal Board, he was quick to

realise the possibilities and impossibilities that mark the running of

an administration in contrast to merely spouting political opposition

to the existing administration.

In the field of

politics, Nehru already had begun to campaign among peasants, been to

jail in Nabha for having supported the Akali agitation. The Congress

subsequently gave him the charge of coordinating with the Akalis. Yet,

he failed to judge the Sikh fear of the Communal Award that came in

1932.

Gopal, unfortunately,

misses out Nehruís insensitivity to Sikh fears. Even the Sikhs in

the Congress, like Caveeshar, walked out of their posts in the

Congress when elections were held in 1936 under the Communal Award.

Gopal also misses out entirely how the young and energetic Sardar

Partap Singh faced up to Nehru during the elections. The Akalis and

Congress had had an adjustment on contesting seats in tandem. Partap

Singh insisted on contesting against the Congress candidate, the

redoubtable and much respected Baba Gurdit Singh of Kamagata Maru

fame. A much-incensed Nehru, even visited Sarhali to campaign for

Gurdit Singh and defeat the young upstart. The election results

surprised the senior politicos. Partap Singh won by a handsome margin.

Ten years later it would be Nehru who would invite Partap Singh to be

his right hand man in Punjab Congress. It would have been good had

Gopal told us of the workings of such equations between a leader of a

national stature and an emerging local leader.

Note: Volume II will be

reviewed next week

|