Illustrations: Sandeep Joshi

Harish Khare

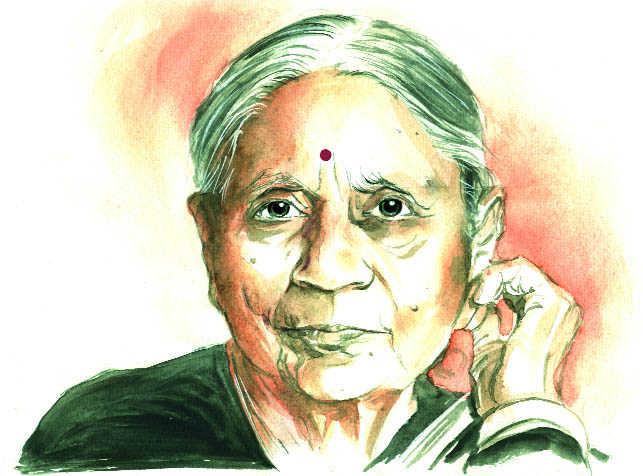

IF I was asked to name five noble souls alive in India, I would unhesitatingly include Mrs Ela Bhatt in the list. I have known her for over three decades and without any fear of contradiction, I can vouch for her nobility. She has influenced the lives of thousands and thousands of poor women, made them self-confident and self-assured and self-sufficient. And I am equally certain that she would not make it to any of those fashionable lists of the “10 most powerful women” that news magazines are so fond of compiling around this time of the year. Empowerment of poor women — and not “power” — is her game.

Fondly called Ela Ben, she is best known as the inspiration behind the Self Employed Women’s Association (SEWA). What began as a women’s trade union and then went on to become a formidable NGO, SEWA is now a Gandhian movement. Thanks entirely to Ela Ben’s nobility, her ideas, values and commitment.

The immediate provocation for bringing up Ela Ben is that she has now put together some of her ideas in a book called Anubandh. It is published by the Gandhian publisher, Navajivan Publishing House of Ahmedabad (no commercial media house would touch it).

Anubandh is a concept that connotes a kind of solidarity, a mutual inter-connectedness. The term was perhaps used first by two eminent Gandhians — Vinoba Bhave and Kaka Kalelkar — though the Mahatma himself never used it.

This slim book is an extremely thoughtful, original work, undertaken primarily from the life experiences of struggling people. Ela Ben is not an anti-market person, but neither is she enamoured by the market and its much-touted magic.

She is still convinced of the relevance of the Mahatma’s teachings. As she puts it: “Mahatma Gandhi firmly believed that strengthening the village economy was the key to removing poverty and exploitation in India.”

And then, she sums up her four decades of experience: “It was the lack of local resources to meet the primary needs of life — food, housing, clothing, healthcare, education and banking — that rendered rural communities vulnerable to poverty, exploitation and migration. If we could meet local needs with locally generated resources, we could benefit the local economy, the local ecology, and the local community.”

Sounds simple. But if one pauses to ponder, her argument becomes appealing. Her basic mantra is that we should build what she calls “100-mile communities”. The proposition is simple: six basic needs — food (including water), clothing, housing, healthcare, education and banking — should be within a 100-mile radius of everybody.

This is so far out, so against the grain of the collective wisdom that we as a nation have come to subscribe to. But this wisdom is not very helpful in sorting out our 21st century afflictions.

We are unable to understand why Chennai is groaning under water, why a city like Delhi has almost become unliveable, how every single big and medium town in India has had a painful brush with a dysfunctional urban governance model. And yet, we seem to be so irretrievably stuck up with doing more of the same unsustainable policies.

Ela Ben is not talking from a moffusil town perspective. In fact, she is a global citizen, though deeply rooted in her Gujarat moorings. She has just been appointed Chancellor of that iconic Gandhian institute, the Gujarat Vidyapeeth.

She is probably one of the most travelled persons. Also, the most honoured and respected outside India. Perhaps, the only one to have been awarded honorary degrees both by Harvard and Yale. She is among the earliest winners of the Ramon Magsaysay Award. There is a shelf-full of other national and international awards to her credit.

In the last 10 years or so, she has been a part of this international group, The Elders, founded by Nelson Mandela. It now includes the likes of Jimmy Carter, former president of Brazil Fernando Cardoso, Kofi Annan and Algerian leader Lakhdar Brahimi. The Elders seek to make humanitarian intervention in global crisis situations.

The ideas she has articulated in Anubandh are authentic because they are based not on some exotic theory, but on the day-to-day experiences of hundreds and hundreds of poor women. Not just Indian experiences, but also the stories she heard in rural communities across Asia and Africa.

Many years ago, she was at some international conference and some farmer women from Ghana told her: “We eat tomatoes and rice. Earlier, we used to grow them on our farms. Now we grow silkworms and buy packaged food from supermarkets, imported. We do not eat what we grow and do not grow what we eat.” When the silk market collapsed, they starved.

Ela Ben’s hope is that young people would read this book and would be able to think differently about how to solve our problems.

THE other day, the Delhi Assembly was reported to have given its legislators a very hefty rise in salary and perks. This decision was predictably criticised along the predictable line of politicians rewarding themselves at the expense of the public exchequer and the common good.

This is hypocrisy. The fact is that we do not pay enough to our parliamentarians and legislators. The fact is also that not all MPs and MLAs are rich or come from rich families.

Over the years, I have known very many MPs in Delhi who can barely keep up the appearances of decent living on their meagre salary. Over half the present MLAs in Delhi come from a very modest background and have little family money to help them carry on their public role.

I think as a society, we should have a vested interest in ensuring that not a single legislator is financially vulnerable. Sure, there is no guarantee that a well-paid legislator would not turn out to be corrupt. However, if we can ensure that even a handful of MPs and MLAs remain uncontaminated, we will be better off as a democracy.

FRIDAY night, I was delighted to have dinner with a distinguished visitor, Sir Hew Strachan. He is a professor, a military historian with a very formidable reputation, both as an academic teacher and as an adviser to various British governments — with five books under his belt and a very befitting knighthood.

He was in town to deliver the Veterans Remembrance Day Distinguished Lecture organised by the Indian Ex-Servicemen Movement, Panchkula. He spoke on “Politics and the British Army”. His subject induced his Indian audience — of ex-servicemen — to try to extract from him a parallel between the British Army and the Indian Army. I was asked to preside over the function. I gladly accepted the invitation as it gave me a chance to meet many interesting former officers. Some of them write for The Tribune and it was a pleasure interacting with them.

Sir Hew Strachan made a charming dinner interlocutor. He discussed history, diplomacy, war, strategy, Cold War and leaders, past and present. He could dissect various British prime ministers without sounding partisan, he was knowledgeable but detached. And, of course, he was keen to know from his fellow dinner guests about Indian military history. A very enjoyable evening, indeed.

PROF Mohan Singh wrote that he found it difficult to appreciate my “prejudiced impressions of Aamir Khan as an actor, director, or a citizen of India. But the title (Face-to-face with our hollowness..., November 29), in the context of the current crisis, reminds me of the poem where TS Eliot says, ‘We are the hollow men, We are the stuffed men, Leaning together, Headpiece filled with straw.’ It’s most unfortunate. Think about it.”

Itching for a coffee break?