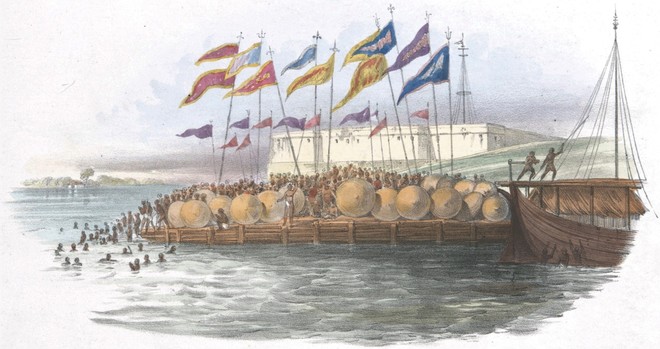

Multitude of priests descending from a budgerow into the Ganga.

BN Goswamy

Every plate is executed from sketches after nature, which I made chiefly during my pedestrian excursions in the interior of the country, on the banks of the Ganges, where the restraints which confine respectable Europeans to the Palkee are laid aside, and they can enjoy in uninterrupted freedom the contemplation of the various scenes presented by the country, and its inhabitants to their view.

— Mrs Belnos, introducing her book

Madam, I have with great pleasure looked over your drawings, and read your descriptions of them, and I now have the satisfaction to inform you, that they are true representations of nature, so much so, that they have served to bring to my recollection, the real scenes alluded to of that unhappy country. …The drawings are so expressive in themselves, that the descriptions however excellent, are scarcely necessary to anyone acquainted with India.

I remain, Madam, Your most obedient Servant.

— (Rajah) Rammohun Roy, writing to Mrs Belnos from London, 1832

It is very unlikely that anyone among us today would know anything about Mrs Belnos as I sit down to write about her and her work: at any rate hers is certainly not a household name. And yet she, a British woman, needs to be spoken about with regard, for she drew, lithographed, and published — a little less than 200 years ago — some of the most sensitive studies of Indians at prayer, as she observed them. Sophie Charlotte Belnos was her full name and, from what one can glean from the extremely thin records that have survived, she was born in Calcutta in 1795; she married a French miniature painter, Jean-Jacque Belnos; and produced drawings on the basis of which lithographs were prepared in 1832 by A. Colin for a book, Twenty Four Plates Illustrative of Hindoo and European Manners in Bengal, which won high praise, including from the highly respected reformer and scholar, Raja Rammohun Roy, as cited above. By 1847, however, Sophie Belnos had emerged from the shadows of others and had, enterprisingly, set up a lithographic press of her own in Calcutta. It is from that press that the remarkable studies I speak of here emerged in 1851: her book bore the unwieldy title: The Sundhya or the Daily Prayers of the Brahmins, illustrated in a series of original drawings from nature, demonstrating their attitudes and different signs and figures performed by them during the ceremonies of their morning devotions, and likewise their Poojahs. There were twenty-four plates in the book, and the title announced that “A descriptive text (was) annexed to each Plate and the prayers from the Sanscrit, translated into English”. This exactly — unlike countless book-blurbs which promise far above what they offer — is what the book contained.

_by_sophie_charlotte_belnos__digitally_enhanced_by_rawpixel_com_7.jpg)

Why would Sophie Belnos zero in on Indian priestly rituals, one would never be able to fathom, for it was an unusual, almost arcane, theme. One knows of course that, under the British, a great deal of work was being done in the country to document and ‘illustrate’ the land that they now almost had come to own: studies of landscape, of architecture, of India’s flora and fauna, above all — there was great curiosity about it ‘back home’ — the trades and professions and callings that Indians followed, their castes and fairs and festivals: the entire gamut covered by what is generally called ‘Company Painting’, in other words. But for Sophie Belnos to pick on this narrow, and somewhat obscure, even intensely ‘private’, field of priestly rituals and devotions to work on, takes one by surprise. One does not know her to have been a scholarly ‘researcher’: a scientist, or anthropologist or orientalist, for example. But, somehow, her interest in all this seems to have been consuming. What she did was to set out to record how ‘Hindoos’ approached their deities and performed worship.

_by_sophie_charlotte_belnos__digitally_enhanced_by_rawpixel_com_22.jpg)

In Calcutta, she must of course have seen priests everywhere: scantily clad, heads often shaven except for a top knot of hair, bare upper part of the body with a sacred thread worn so as to cross the frame, and an unstitched lower garment, the dhoti. She must have quickly come to learn that the objects of their devotion differed: it was the great god ‘Vishnoo’ for one, and the ‘Devee’ for another; ‘Shiva’ for this person and ‘Soorya’ for the next. Each had his own way of chanting, of using implements of worship — the ‘urgha’, the ‘ghunta’, ‘the arutideep’, the ‘shunkha’, the ‘dhoopdaun’, and so on — and each made mysterious, lightning-quick gestures with his hands while chanting. This was the world Sophie Belnos wanted to, and did, enter: in her own words, “I resolved to engage in the accomplishment of a task which had hitherto been unattempted …” But she had to encounter ‘difficulties as serious as unexpected’, since a general sketch of ‘attitudes and gesticulations’ is not what she was interested in: she was looking for an ‘opportunity to delineate them with precision’. This amounted to “asking the performer to exhibit rites considered by him as solemn and sacred, for a secular and profane purpose”. Nearly all of the priests, at least in Calcutta, refused, she recorded in her book: “none of them would consent to perform those rites in my presence, or impart to a female, and an impure European, any of the mysteries of their religion”. Not being able to make any progress in Calcutta, therefore, she undertook a visit “to the Upper Provinces, and to the Holy City of Benares” where she hoped “to meet priests less intolerant”.

_by_sophie_charlotte_belnos__digitally_enhanced_by_rawpixel_com_14.jpg)

Did she succeed? One has only to look at the illustrations, including the stunning image on the cover of the book — a multitude of priests descending from a ‘budgerow’ into the sacred waters of the Ganga — to see how splendidly she did: turning out crisp, precise, finely drawn, uncluttered, acutely observed studies of different priests in different locations: by the waterfront, inside a temple, on a riverine island, and so on. The quality of her images remained amazingly constant, but there is something truly remarkable — observation, sympathy, wonder, all combined — about the way she renders a priest paying homage to the Sun, standing, eyes protected from its brilliance but one eye looking up and gaining darshan through an aperture made in the interlaced fingers in front. It is moving.

Join Whatsapp Channel of The Tribune for latest updates.