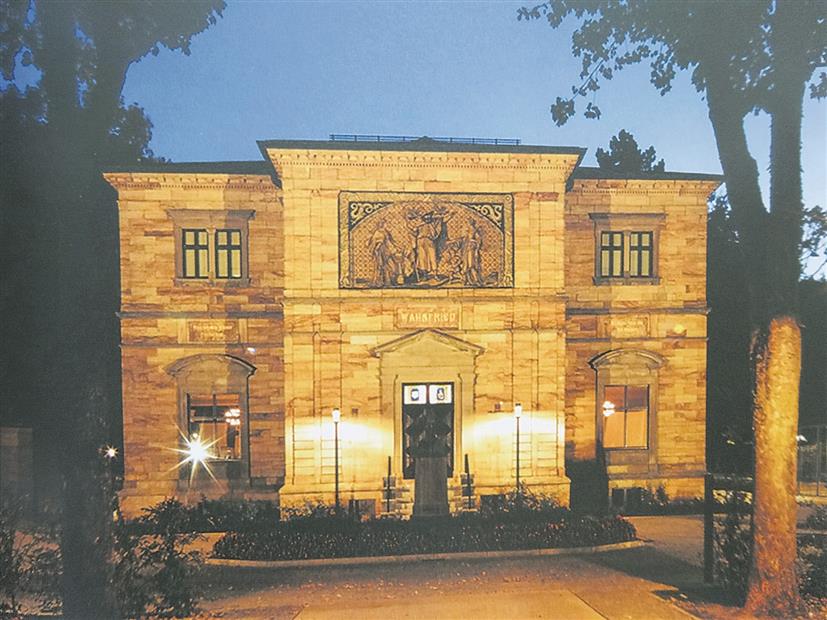

House Wahnfried in Bayreuth, Germany (where the Bayreuth Wagner Festival is held every year)

BN Goswamy

Wagner could not keep quiet. He had an enormous gift of the gab … but was full of oppressive ideas and impossible to listen to for any length of time. — Robert Schumann on Robert Wagner

Wagner was a man without boundaries, a man connected to his ‘inner infant’; a master dramatist of his life and an actor of astounding gifts (“more an actor than a composer,” Nietzsche thought); a man who, for better or worse, imposed himself and his work on the world as perhaps no other artist in history had done. ... He was, as his operas were meant to be, a Gesamtkunstwerk, a total, all-embracing work of art: a great work of his own imagination that he performed endlessly. He could not stop himself. — From Simon Callow’s essay on Wagner

Even though not many here might be on familiar terms with the work of Richard Wagner (1813-1883) — great dramatic composer and theorist as he was, someone ‘whose operas and music had a revolutionary influence on the course of Western music’ — two things are likely to be known. One, that some of the most famous works of Western music, like The Flying Dutchman, Tristan and Isolde, Siegfried, Gotterdammerung, Meistersinger, Parsifal, were all his; and, two, that he was a musician around whose work and whose personality more controversies have raged over more than a century and a half than about any other. That he harboured anti-Semite views, that personally he led what may be described as an amoral life, that Hitler was a great admirer of his and consistently used some of his writings and his music to push his Nazi agenda: these are a few of the issues which have never quite gone away.

And, yet, there were, and always have been, a large number of die-hard, unquestioning, admirers of his. I became aware of this, personally, all the time that I was in Zurich. In that wonderful city it was to the Rietberg, my favourite museum in Europe, to which I was always headed. That Museum is situated atop the lovely Rieter Park, occupying the building which bears the name Villa Wesendonck, and the name Wesendonck is seldom unaccompanied by the name of Richard Wagner. This because the composer is known to have had a long and passionate affair with Mathilde Wesendonck, wife of a rich merchant, Otto Wesendonck, who had built that elegant villa and lived in it. The details of that scandal are of no concern to this piece, as they are not to Wagner’s devotees, for, to this day, small groups of them trudge up to the Villa sometimes, not so much to see the Museum as to have just a glimpse of the place where their hero had once spent a measure of time.

In the Rietberg itself there is no more than a whiff of the memory of Wagner now but, just recently, I got to know of a whole museum, elsewhere in Switzerland — at Tribschen, situated idyllically on the edge of Lake Lucerne — that is dedicated to the famous composer. Wagner was German, not Swiss by birth, but he moved about a great deal in his life, and Tribschen was where he spent six years of his life, from 1866 to 1872. This was a period of relative quiet for him in which he composed and wrote and performed; this also was the period in which he pursued his love for the lovely Cosima, daughter of the great Hungarian composer and virtuoso pianist, Franz Liszt. That Cosima already had a musician husband was, for Wagner, no hindrance, and he eventually ended up marrying her. One mentions all this because here, at Tribschen, Wagner seems to have been deliriously happy. His troubled and somewhat fiery younger days in which he had taken part in the 1848 revolutions were behind him; the young and impressionable King of Bavaria, Ludwig II, had turned into an ardent devotee of his music and was supporting him financially; and Tribschen was beautiful. One pays attention to the words in his diary, soaked in happiness as they are. In the early hours of a morning, standing at the edge of the lake, he wrote: “Such a morning is worth any price, even in the challenging winter …The birds are vivacious and are singing humorously…. Magnificent cows cover the surrounding fields: you can hear their bells day and night. This ringing is more beautiful than any sound I know: the random changes in tone, the incredible bells, are indescribably magical. I would trade all of the bells in Rome for that!” On another occasion, he wrote: “Wherever I turn, upon leaving my house, I am surrounded by a veritable wonder world: I know no more beautiful, no place in the world that feels more like home than this.” Here he composed, among so many other masterworks, a piece for the birthday of his beloved Cosima to whom that music played in the early hours when she was just waking up came as an utter surprise; 15 musicians playing: two first and two second violins, a cello, a bass, a flute, an oboe, two clarinets, a trumpet, two horns and a bassoon. Cosima wrote later that she was in tears with happiness.

It is this period of happy times and redolent memories that the city fathers of Lucerne decided to keep alive when they, with considerable effort, raised enough money to buy out the Tribschen Manor in 1930 and turn it into a museum honouring their idolised composer. Objects belonging to Wagner either still stood there, or were collected, as Gaby Lutz, who brought the museum to my attention, noted: the Erard grand piano which he loved (‘what a joy it is to play it: it requires the lightest pressure, hardly a touch’, Wagner had written once); Lenzbach’s portrait of Cosima; a cast of Wagner’s death mask; the appointments in the room where gatherings used to be held; portraits of other people or paintings that the composer cared for; the cage where he kept his pet peacocks, Wotan and Fricka; even the soft silk slippers he used to wear around the house. Today, visitors can stand where he once stood, looking down on ‘a rolling sea of leafy green … rippling from hillside to valley down to the clear blue lake, across which several white sails glided, and in which the violet hues of the high peaks were reflected’, as someone noted. One can almost hear someone playing a piano inside.

Join Whatsapp Channel of The Tribune for latest updates.