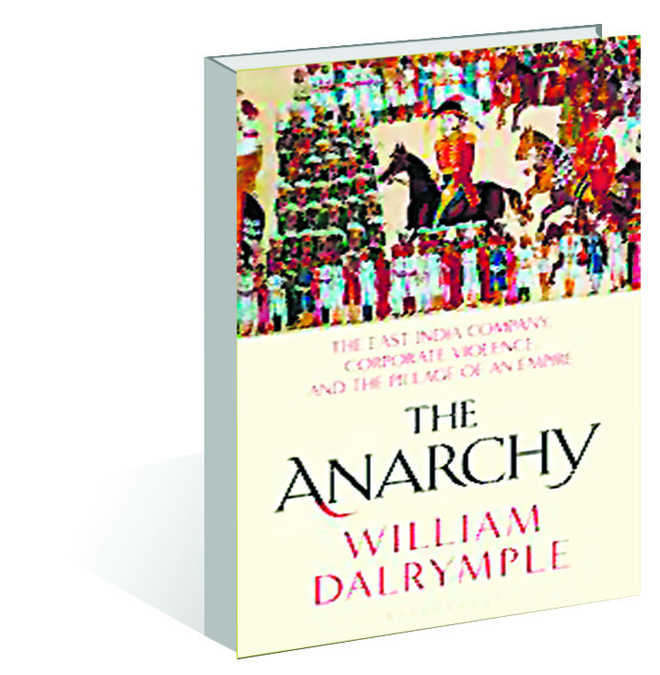

The Anarchy: The East India Company, Corporate Violence, and the Pillage of an Empire by William Dalrymple. Bloomsbury. Pages 522. Rs 699.

Aditi Tandon

Never before has any historian dealt with such great depth the period between the Mughals and the British Raj in India as William Dalrymple in his new book, The Anarchy. This Bloomsbury publication is a riveting tale of how the East India Company, a conventional trading corporation, rose to become an aggressive colonial power and subdued the entire Indian subcontinent by 1803.

William Dalrymple spoke to The Tribune about the journey of the company in India and warned against lurking dangers of modern-day multinationals.

Excerpts:

What was your trigger to write this book?

There’s a tendency in India to research the glorious periods of history — the golden age of the Guptas, Ashoka, Shah Jahan, Akbar, the freedom struggle, but I think the period between the Mughals and the Raj is a much underwritten period. One of the things of huge pleasure about this field is that you can find stuff no one else has ever accessed. The Persian sources are virtually virgin. One of my discoveries for this book is Comte de Modave, a friend of Voltaire, who wrote a four-volume travel book on the mid-18th century India.

What new historical sources have you tapped for this project?

There are lots of new sources, particularly on the Mughal side. There has not been a proper book on Mughal Emperor Shah Alam since the 18th century. We spent time at Maulana Abul Kalam Azad Arabic Persian Research Institute, Tonk, Rajasthan, to translate a previously unused biography of Shah Alam, the Shah Alam Nama by Munshi Munna Lal. We also used translations of the more obscure sources such as the Ibrat Nama, or Book of Admonition by Fakir Khair ud-DinIllahabadi, or the Tarikh-i-Muzaffari by Mohammad Ali Khan Ansari of Panipat. Then there are the unused French sources.

You have written about this region before. What’s the principal theme of this book?

I have done three micro histories of the region in White Mughals; Last Mughals and The Return of the King. Suddenly, I thought I needed to know what the East India Company’s hold did to this country. The company was the first great multinational and yet people confuse it here and in Britain for The British in general. But it is not the British any more than the Facebook is American. For 172 years, starting 1599 when the company is founded, there is no state control on it. From 1772, when the company nearly goes bankrupt and has to be bailed out because “it’s too big to fail”, the state begins to supervise.

Nonetheless, it is not the British army that conquers India. It is Indian troops. The audacious story that is most incomprehensible to a modern reader is the fact that there were never more than 2,000 Brits in India ever. These people borrowed money from Marwari and Jain bankers and trained Indian troops to fight others and by 1799, they had 200, 000 troops, twice the size of the British Army.

Why did the Indians collaborate?

The Indians took the decision that in financial terms the company was the safest home for their capital. It might do horrible things but it would repay the interest in time. Politically, they made a decision that the company was a lesser evil than other choices such as the Marathas, Scindias and Holkars, who were fighting battles against each other. India in the mid-18th century was massively fractured.

What kind of a commentary is that on Indian patriotism?

We are dealing with the 18th century here. I think many people would say that while India has definitely been a spiritual, geographical and cultural entity for thousands of years, it simply hasn’t been a single political entity ever before the British. No empire whether the Guptas, the Mauryas, or the Mughals ever united the entire country. So, in a sense, the biggest legacy of the company was the act of forced political unification of India. And that, ironically, in due course backfired against the British because it did create a sense of national unity and nationalism. There, clearly, wasn’t the same sense of patriotism in the early and the mid-18th century as there was in the early and mid-20th century or as it is today. Today, in a sense, India is at the very opposite end of the story in that whatever one thinks of this government, there is no question that it is a strong and unified government.

What is your reading of Shah Alam, the only Mughal emperor, to feature in the book?

He’s the tragic anti-hero. When the book opens, he is young, good looking, a poet, fights his way out of Delhi, survives an assassination attempt; keeps fighting the British, and yet, is always dogged by bad luck. In the end, he gets blinded by his own former favourite but he is a very attractive character. Shah Alam creates the model of late Mughal kingship that Bahadur Shah Zafar goes on to embody, one of a cultured, poetic, tragic figure, dispensing Sufi wisdom from the Red Fort. The defining moment in the territorial rise of the company is also the moment in 1765 wherein Shah Alam signs off tax collection rights in Bengal, Bihar and Orissa to the company.

How does Robert Clive of the company contrast with Shah Alam?

Clive and Sham Alam are almost exact contemporaries born two years apart and yet totally opposite. Clive is every bit as effective as Shah Alam is ineffective. Clive is totally uncultured and yet he is the man who creates the company state. In the end, Clive commits suicide. Karma catches up. His conscience can’t survive his crimes in India.

How vulnerable are modern nation states to the influence of corporations?

Very much so as we have seen in recent history — in 1953 one company got the CIA to overthrow Prime Minister Mohammad Mosaddegh of Iran; in 1954, United Fruit created a coup in Guatemala; in 1977, CIA used the ITT to overthrow the Government in Chile. There’s also the question of how far ExxonMobil was responsible for the Bush administration’s invasion of Iraq.

What, in your conclusion, is the biggest threat nation states face from the MNCs?

In India, we saw the Congress’ relationship with corporations. Then we saw the 2G scam, the coal scam. Any political party anywhere needs funding and the best funding comes from MNCs. There is always an unstated quid pro quo. When Exxon donates to the Republicans, when the Ambanis donate to Narendra Modi, who knows what the understanding is? It is hardly news that India’s big corporations have very powerful political interests. Would the Modi government have got in the previous elections without the massive support of corporate India? The East India Company itself was invented as a corporate lobby. In the first case of a corporation bribing parliamentarians in 1697, the company was found offering shares to MPs if they voted to extend its monopoly. These things continue to this day — in India, the US and the UK.

The lesson your book holds for the future?

The lesson lies in the words of Edward First Baron Thurlow, the Lord Chancellor, during the impeachment of Warren Hastings, “Corporations have neither bodies to be punished, nor souls to be condemned, they therefore do as they like.”