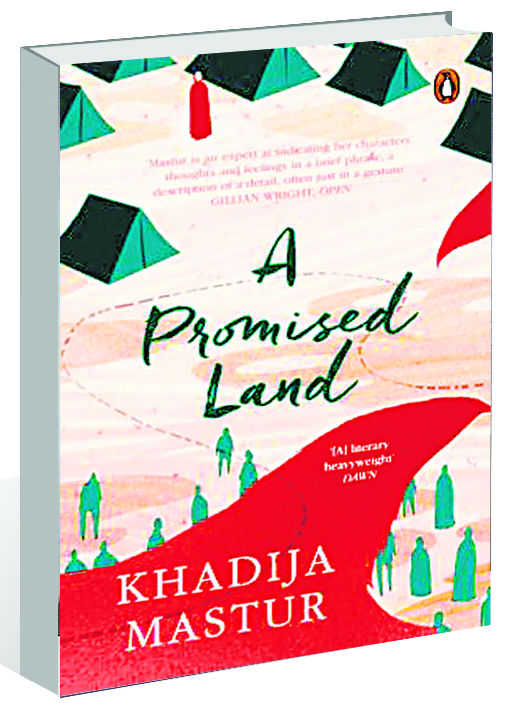

A Promised Land by Khadija Mastur translated by Daisy Rockwell. Penguin. Pages 230. Rs 399

Geetu Vaid

Each birth is blood-stained and pain-soaked, but it is the promise of a new and better tomorrow that makes it worth all. But won’t all the anguish, tears and bloodshed seem futile and frustrating if a birth just perpetuates the pain and trauma? It is this query that writers chronicling the Partition of India have raised over the past 70 years. Whether it is Manto’s stories or Bhisham Sahni’s Tamas or Khushwant Singh’s Train to Pakistan or Salman Rushdie’s Midnight’s Children, the undercurrents of futility of the loss of lives and property are evident in all.

Khadija Mastur’s A Promised Land begins on this familiar terrain with a distraught father’s heart-wrenching wail for his missing daughter at a refugee camp in Walton. Here each one of the survivors carries the burden of violence and a close shave with death.

Beginning from a period immediately after the Partition as the displaced gear up to pick up the pieces and start rebuilding their lives, the author highlights how the promise of a free and egalitarian society remains a mirage. Young Sajidah, who has escaped the savagery of riots, finds it difficult to fight the misogyny that is deeply entrenched in our society.

Khadija subtly stokes the embers of irony to drive home the point that rape and abuse is not confined to any religion, race or class.

She gives a women-centric hue to the narrative by baring the dark underbelly of a social structure where rape, repression and subjugation are common. Post-Partition women, like the abandoned properties, were vulnerable to being “occupied and claimed” by men trying to “improve” their social status. Mansions whose locks have been broken by occupiers, orchards and land are used as striking metaphors as the author breaks the illusions of love, filial responsibility, integrity and loyalty.

In a social fabric tattered by displacement corruption, falsehood and hegemony raise their ugly head soon enough as “class” differences take root even among the refugees in the new country.

Left alone (unclaimed) after the sudden demise of her father in the refugee camp, Sajidah realises how difficult it is for a woman to survive on her own. Her “shifting” to the Malik household with Saleema just adds to her insecurities. While Sajidah vociferously fights for her self-respect, Taji, another girl from the camp brought to Malik household and used as a house help, is incapable of fighting her fate of rape and abuse.

Class, education and grit are poor shields for a woman in a male-dominant system. Thus, while Taji becomes an easy prey for Malik’s son Kazim, Sajidah also has to work out a ‘compromise’ to marry Nazim, in order to avoid his ruthless younger brother.

Khadija’s vast canvas in this book includes women from different strata of society, age groups and marital status. Each of these characters is, in fact, looking for a better life and future promised by a man in her life. The irony is that this promised “land” is nothing but a mirage for all of them.

The promise of equality on a social level is also a hollow one, as Nazim realises in the newly formed Pakistan. As corruption, injustice and subversion of human rights continue, Nazim is soon disillusioned with the dream sold to youngsters like him. And he pays a heavy price for voicing his dissent.

Khadija’s narrative maintains an easy pace and she allows ample time to the readers to grasp the irony and understand the metaphors. The thread of melancholy is unmistakable in the warp and weft of the plot as each event exposes some facet of hypocrisy around us.

Characterisation, however, can’t be called a strong point of the book as most of the characters remain either sketchy or too predictable to establish a deep emotional connect. The fact that this is a translation of the original in Urdu is also quite obvious to be overlooked at places. This has, to some extent, added to the detachment that one feels as a reader from the trials and tribulations of the key characters.