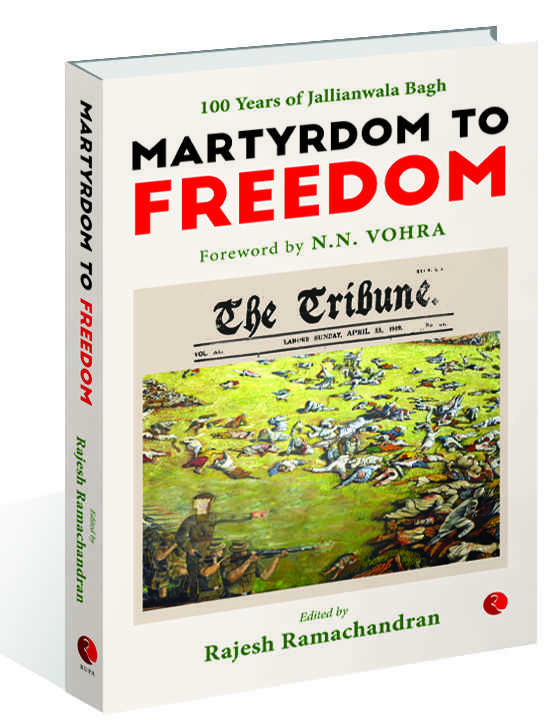

Martyrdom to Freedom: 100 years of Jallianwala Bagh edited by Rajesh Ramachandran.

NN Vohra

Born in Punjab about a decade and half after the Jallianwala Bagh massacre, I grew up in an environment which was intensely surcharged by stories of this gruesome incident and the untold atrocities which continued to be perpetrated by the British. Writing this foreword has rekindled frightening childhood memories of the sufferings undergone by the people of Punjab during the prolonged struggle for the attainment of national freedom.

The Jallianwala Bagh carnage, in which over a thousand innocent persons, young and old, were cold-bloodedly shot to death, took place on 13 April, 1919. This horrific event, which demonstrated the brutality to which the Empire could descend, had unleashed a wave of revolutionary fervour which gave a tremendous boost to the battle for self-determination and marked the beginning of a chain of events which ultimately led to India gaining liberation from the colonial yoke.

Among the thousands who volunteered to join the freedom struggle was my maternal grandfather, Chintram Thapar of Lyallpur, who spent nearly two decades of his life in the British jails. And among the many young revolutionaries who laid down their lives fighting to throw out the colonial masters was Sukhdev, my maternal uncle, who, at the age of twenty-four, was executed by the British, along with his comrades Bhagat Singh and Rajguru — all three of whom had been declared ‘militants’.

***

To ensure against any arising factor which could thwart the achievement of their objectives, the British had been, astutely, appeasing certain elements and, alongside, enforcing their oppressive regime. Encouraged by the then prevalent belief that the success of the Allies would pave the way for the emergence of a new global system, which would bring freedom to the colonised millions, India provided strong support to the British in the First World War. Even the Congress Party, along with the Muslim League, had harboured high expectations that as soon as the War was over, the British would lose no time in taking steps which would pave the way for self-determination.

The people of Punjab had borne the brunt of the ruthless coercion employed by the British for extracting loans, enlisting recruits and securing varied support for the ‘war effort’. Having faced acute economic distress for many years, they had cherished high hopes — much more than their compatriots in other parts of the country — of receiving compensations and rewards once the War was over. But this was not to be.

The promulgation of the Government of India Act of 1919 crushed the expectations of all those who were fighting for self-determination and those who had been led to believe that the end of the War would see changes leading to the advent of democracy. Notwithstanding the hype about the governance reforms then underway, the provisions of the 1919 Act left no doubt whatsoever that effective control over the administration of India would continue to remain entirely in the hands of the British Viceroy, British governors and British ministers who had manoeuvred to retain control over the key departments in the provincial governments.

Sir Michael O’Dwyer, Lieutenant Governor of Punjab, was a ruthless official. He had used strong-arm methods and untold coercion to top the list of Governors who had mobilised the maximum contributions for the War. Besides extracting large collections for meeting the military expenditure, the British had enlisted over twelve lakh troops and supporting elements to fight their war in various parts of the world. Of the over one lakh soldiers who were killed in combat, the maximum losses were suffered by Punjab, which had contributed over 60 per cent of the total recruitment.

Leave aside being recompensed for their sacrifices, the people of Punjab were subjected to ever-increasing repressions by O’Dwyer's administration. While there was growing unrest in various parts of northern India and elsewhere, Punjab witnessed widespread disorder in 1919.

When the War began, the British had quickly passed the Defence of India Act. This law, which blatantly violated the fundamental principles of civil rights and liberty, empowered the government to arrest, detain and impose varied restrictions on the citizens; set up special courts to carry out summary trials which could, even on the basis of hearsay evidence, award non-appealable sentences for life or even death penalties; and detain any person without trial, on mere suspicion, for the alleged objective of securing ‘public safety’.

The British did not consider the Defence of India Act to be adequately repressive! In March 1919, despite vociferous opposition from the Indian representatives in the Legislature, the government enacted the Rowlatt Act which provided for arrests without warrants; without-trial detentions for indefinite periods; and without-jury trials of political detainees. These ‘black laws’ unleashed a fresh wave of protests all over the country.

It was at this juncture that Gandhi, having failed to persuade the Viceroy to withdraw the infamous Rowlatt Act, decided to go into action. On 6 April, he launched an all-India Satyagraha and called for a hartal across the length and breadth of India. This hartal, which resulted in the closure of business over almost the entire country, was the first successful pan-India general strike which was reported in The Tribune in the following words: ‘…whenever a member of a family dies the other members of the family keep fast and suspend all business till the dead body is taken out of the house. Now, when the dead body of the Rowlatt Act is still in our midst, we have suspended all business and must remove the corpse from the house before the people can break their fast and resume business’.

Considering the pivotal role played by the fearless people of Punjab, Gandhi decided to commence his movement in this province. However, he was arrested before he could enter Punjab and sent back to Bombay. This increased the anger of the masses and further aggravated the already disturbed environment. To protest against Gandhi’s arrest, a large group of Hindus and Muslims decided to peacefully parade the streets of Amritsar on 9 April. O’Dwyer ordered the arrest and deportation, without trial, of Dr Saifuddin Kitchlew and Dr Satyapal, who were among the most prominent leaders in this procession. The next day, 10 April, a group of citizens peacefully marched to the Deputy Commissioner's residence to appeal for the release of their arrested leaders. They were fired upon; three were killed and several injured. Peaceful protests having failed, the angry citizens resorted to arson and looting of offices and banks. In these riots, many were wounded and several killed, including three Britons.

Amritsar was handed over to General Reginald Dyer, who placed it under unauthorised martial law and launched a fresh wave of terror. Pushed to the end of the tether, the people of Amritsar decided to hold a public meeting at Jallianwala Bagh on Baisakhi, an important Punjabi festival, which was to be celebrated on 13 April — which happened to be a Sunday.

As per the Punjabi tradition, people in very large numbers came out to celebrate Baisakhi and thousands gathered at Jallianwala Bagh. It was not known to any of them that, on the previous night, General Dyer had surreptitiously issued an order to ban any public gathering in the Bagh.

On being informed about the large number of people who had collected in the Bagh, the General decided to personally lead his troops. He deployed them at the only exit gate of the Bagh and gave a ‘shoot to kill’ order, directing that they shall return to the barracks only after fully exhausting the 1,650 rounds of ammunition issued to them. As per the official statement, 379 persons were killed and 1,208 wounded in the firing. However, as per the non-official sources, over 1,000 were killed and several thousand injured. To ensure that the dead bodies could not be removed for their last rites and the wounded could not be taken to hospitals for treatment, Dyer maliciously enforced a curfew which prohibited any movement whatsoever in the city that day.

The Martial Law Commission set up by General Dyer held daily sittings to conduct summary trials and award prison terms or instant executions. To warn the citizens to ‘behave better’, Dyer ordered stoppage of water and power supply to the city. Further, anyone who was reported to have shown disrespect to the imperial masters was flogged on a public platform, specifically set up for this purpose.

Governor O’Dwyer, not wanting to lag behind the General, imposed martial law in the entire province and let loose a barbaric wave of repression. To ensure that news of the terror perpetrated by him did not reach the rest of the country, he took special measures to gag the newspapers.

After several months, when fuller news about the bloodbath in Punjab finally leaked out, a wave of shock and terror enveloped the country. To express his anger, Nobel Laureate Sir Rabindranath Tagore renounced the knighthood which he had received in 1915. In his open letter to Lord Chelmsford, Viceroy of India, Tagore wrote: ‘…the very best I can do for my country is to take all the consequences upon myself in giving voice to the protests of the millions of my countrymen, surprised into a dumb anguish of terror’. And Gandhi returned the Kaiser-i-Hind gold medal.

The British Government took an almost unconcerned view of the Jallianwala Bagh incident. After a meaningless ‘enquiry into the facts’, General Dyer was merely asked to resign and no action was taken against Governor O’Dwyer. However, twenty-one years later, he was shot to death in London by a survivor of the massacre.

The Jallianwala Bagh massacre had several consequences. It marked the end of India’s cooperation and support to the British; promoted Hindu-Muslim understanding and gave a boost to the ‘revolutionary’ groups whose activities aimed to 'terrorise' and 'destabilise' the British administration with the ultimate objective of ‘overthrowing the British Government of India’. And Gandhi’s Satyagraha, post Jallianwala Bagh, is a crucial landmark in the history of India's freedom movement. It placed him on the centre stage of the national struggle.

***

The revolutionary spirit of the people of Punjab and their contribution to the freedom struggle was fearlessly chronicled by The Tribune, a newspaper then published from Lahore which was established in 1881 by Sardar Dyal Singh Majithia, an outstanding leader, philanthropist and visionary nationalist. It is a matter of great pride and gratification that this newspaper, which is 138 years old today, has continued to fearlessly serve as the ‘Voice of the People’. The Tribune archives, reflected in the second part of this volume, bring alive the Jallianwala Bagh massacre and the crimes against humanity perpetrated by the British.

2019 marks the centenary of the annus horribilis, 1919. A century — and more — ago, The Tribune gave fearless expression to the voices of the oppressed masses. Kalinath Ray, the eminent Editor of this newspaper at that time, wrote unsparing editorials to denounce the atrocities carried out by the barbarous British administration.

Ray was arrested; O’Dwyer’s martial law court labelled his writings 'seditious' and sentenced him to two years' rigorous imprisonment. The Tribune was fined and its publication was suspended. While arguing for Ray's acquittal and immediate release, Gandhi stated that ‘…in every case, the writer has fortified himself with what he believed to be facts, and which, so far as the judgment allows us to see, have not been controverted’. However, the court had already decided to jail the Editor.

It was the unflinching determination of Kalinath Ray, and a few others of his ilk, which ensured against newspapers being totally blacked out by the endless restrictions which were imposed on their functioning.

— Foreword to the book excerpted with permission from the publisher