R.K. Raghavan

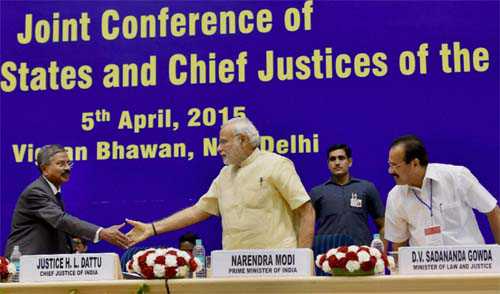

IF the politicians or the government make a mistake, there is a scope to repair the damage by the judiciary. But if you commit a mistake, then everything will end.” —Prime Minister Narendra Modi at the conference of Chief Justices in New Delhi in the beginning of April.

Democracy thrives on candour and dissent, as long as they do not degenerate into slander. Bereft of them we will have a public administration that could be both blind and insensitive. Prime Minister Modi's no-punches-pulled speech at the joint conference of Chief Justices of High Courts a few weeks ago was marked by some refreshing outspokenness.

He was possibly speaking from his heart, a quality honed by his long innings at the executive in Gujarat. His address on this important occasion caused some eyebrows to raise. His detractors seem to believe that he spoke out of tune. His admirers however don't think so. The truth lies somewhere in between.

Agreed that the executive and judiciary should not have too cozy a relationship, if the independence of the judiciary has to be real and respected. The two should not at the same time spar so that the stability and credibility of our already battered criminal-justice system are not further damaged. I think the two important arms of our governance structure have achieved this delicate balance in India. This may not have been wholly the product of any enlightenment. A healthy relationship has possibly been arrived at by the sheer realisation of the wisdom of peaceful coexistence.

Judicial activism

In this context, the judiciary's role in fixing a system that is in a dangerously bad shape cannot be overemphasised. If the Delhi conference focussed only on infrastructure needs of the judiciary, and did not address substantive long- term issues, such as judicial independence, sentencing policy, prison conditions, the state of policing, etc., it could well have been a missed opportunity to at least partially repair the current woeful state of our criminal-justice ( CJ) system.

Critiquing the criminal justice system

It is in this context that a recent conversation two US Supreme Court judges —Justices Anthony Kennedy and Stephen Breyer — had with the members of the Appropriation sub-committee of the House of Representatives of the US Congress seems relevant to the Indian scene.

The two eminent judges seemed conscious on this occasion of the many critical issues that had badly affected the American system. The nonchalant executive intrusion into the privacy of homes and individuals, bias against the African-American community displayed by a nearly lawless and trigger-happy police machinery and an abominable overcrowding of prisons are the main concerns of the US judiciary.

Justice Kennedy minced no words on the occasion, and was categorical that the criminal-justice system had in fact broken down. Kennedy spoke mainly about the all-round lack of interest in Corrections as a palliative to any country's problems in ensuring justice to both the offender and victim. In the judge's perception, crime and its punishment unfortunately dominated the mindset of all concerned, including lawyers, to the sad exclusion of all other relevant issues. For instance, the costs of long incarceration, especially solitary confinement, were often ignored. Although, he had, in the past, upheld abnormally stiff sentences, including 20 to 25 years in prison for two convicts in California for a series of thefts, Justice Kennedy had also ruled against death for child rape, and life sentences without parole, especially for juveniles.

He had also deplored overcrowding of prisons in California, as this affected the mental and physical health of inmates. His colleague, Justice Breyer, who was also part of the exchanges with the House sub-committee, had always ruled in favour of compassion in the matter of sentencing, and viewed a mandatory minimum sentence as abhorrent to human values.

To link this discourse of Justices Kennedy and Breyer to the Indian context will not be inappropriate. We are both large countries with diverse populations. We share most of the problems that afflict the US system, possibly in a slightly modified form.

To be fair, with all its faults, the Indian judiciary has given a reasonable account of itself and has generally maintained its credibility. Integrity at some levels in the judiciary is indeed a concern. This should not, however, drive us into making harsh generalisations. The common man still invests courts with a solemnity that warms most of us in the system. The proposed National Judicial Appointments Commission (NJAC) legislation is no doubt controversial. It is worth an experiment. If the law passes muster with the Apex Court, it is hoped that the few aberrations we have had in our system in the matter of judicial appointments could become fewer.

One other stick with which the judiciary is often beaten is the unconscionably long process of handling cases. There are far too many players here which makes things complicated and unresolvable. I do not see any prospect of things changing for the better in the near future. Too much of judicial accommodation to some unreasonable and demanding lawyers, and poor quality of prosecutors have caused avoidable damage. Only a greater respect for the victim and his rights can bring about a measure of improvement. At present this appears a dream rather than practicality.

My main concern in all this is the role of the Indian Police in making or marring the image of the CJ system. Being the first responder to a common man in distress, its function is crucial. The enormous contribution of the police to the country's social stability cannot be denied. At the same time, it does not absolve it of its many omissions and excesses. The unsavoury image the Indian Police it has acquired over the years has made it lose most of its credibility.

Decline in policing

Reasons for the decline of policing in India are not far to seek. First is its size: only about two million policemen to take care of a 1.2 billion population. There is a mismatch here that does not brook any delayed action. Any accretions to the existing numbers should however be to strengthen the grass roots — police stations — and not to the rapidly burgeoning VIP security corps. The law-abiding citizen would like to see more uniformed police presence in the streets. He would be happier with strong and fast-acting police stations. At present, the latter are shockingly poorly staffed.

Corruption-ridden recruitment

Another sad fact is that recruitment to the police forces is corruption-ridden, with both the political executive and segments of police leadership coming to adverse notice for their venality. It is not as if only poor quality comes in. The fact is there is stiff competition for police jobs — both for the right and wrong reasons — as a result of which, even the meritorious ones who are chosen after a well-conceived and rigorous process will have to grease some palms before being appointed.

Policemen who have had to pay through their nose to join the force can hardly be expected not to try to recover their “investment” in their early years in the force. This is the root cause for their abominable exploitation of every conceivable opportunity to harass the common man and extort money from him, even when the latter had not transgressed any law.

The traffic police are the worst offenders in this regard. This is despite many checks and balances that have been set up in the past few years. Further technology in the monitoring of enforcement personnel is the only way to reduce misconduct that has cost both the police and public dearly. The public consensus is that, it is the traffic policeman in the streets who ultimately makes or mars the image of the police. Focussed attention to enhancing integrity levels of the policemen on the beat alone will help transform the scene. Nothing else will work.

By all accounts the despicable practice of police torture of crime suspects has come down a little. This has, however, not been due to better training or enlightenment. I believe that a greater public awareness of their rights, intense media vigil and stiffer court sentences slapped on erring policemen have alone helped.

It is unfortunate that we are yet to witness any major change in police perceptions of the need for humane beaviour. I do not see any hope for things to change, unless there is enlightenment brought about by the joint endeavour of the executive and top police leadership. Anything short of a serious exercise on a day-to-day basis will not bring about measurable results.

Honest & humane system

In the final analysis, we need an honest and humane system that satisfies the public. All citizens, irrespective of caste and creed, are entitled to high quality criminal-justice protection against executive arbitrariness and assaults by the underworld. A system that fails to afford this has no reason for its existence. Commissions and committees appointed till now have at best been only a patchwork. They have achieved only a little in the direction of enhancing the quality of criminal-justice service delivery. There are no silver bullets here. Persistent and well-conceived programmes in the areas of public administration seem to be the only plausible route to fulfilling citizen aspirations.

The writer was Director, Central Bureau of Investigation, New Delhi.