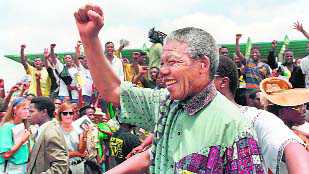

Part Hero: Mandela was courted by leading corporate executives, who saw in him the best hope of politically defusing the situation. His African National Congress obliged.

MK Bhadrakumar

THE legacy of a man of history must be weighed principally from two scales — one, the man himself and what he meant to others, and, two, his achievements and contributions. A perfect equilibrium is never possible and Nelson Mandela’s legacy is no exception. Mandela’s charisma as one of the 20th century’s foremost humanists actually forms part of a complex mythology, which was more a construction that became necessary during the anti-apartheid struggle in South Africa. The legend was born in the apocalyptic moment of his release from prison, and was far from accidental.

The biographical details do not add up to qualify Mandela for such high figuration. The finest part comes when this Black professional belonging to the new African middle-class in Johannesburg, who redefined mass defiance and African nationalism in the 1950s and established an armed struggle, was sentenced to life imprisonment and spent the next 27 years in prison. It was a period of social insurrection, with mass strikes and boycotts, brutal state repression, untold deaths and arbitrary detentions and imprisonment. And the international anti-apartheid movement elevated Mandela to a special status as the fountainhead and symbol of South Africa’s liberation by launching the famous “Release Mandela Campaign”.

In short, the elements of his exile, imprisonment and final return — “homecoming” in the popular mythology — went into the construction of Mandela’s aura and charisma. The 27 years in prison didn’t leave even one iota of vengefulness in the man. Although he was singularly responsible for launching the armed struggle against the White regime, ushering in the harshest Apartheid years, this avenger in popular narratives used the messianic power ascribed to him whilst in prison to argue as he walked free on February 2, 1990, to throw guns into the sea, befriend the Whites and pardon everyone.

To a rally of some 2 lakh people in Durban on February 25, 1990, two weeks after his release, Mandela said: “My message to those of you involved in this battle of brother against brother is this: take your guns, your knives, and your pangas, and throw them into the sea. Close down the death factories. End this war now.” To the masses of youth from the war zones listening to him, Mandela sounded an out-of-touch patriarch. And all this while the man was also struggling with a bitter family drama of his own, which led eventually to his final harsh estrangement from wife Winnie Madikizela-Mandela.

However, a quarter century later, although apartheid ended, South Africa remains one of the most unequal societies in the world. The limited political gains that were made have not translated into greater social and economic equality. An estimated 10 per cent of the population owns 90-95 per cent of all assets. Rather, more South Africans now live in poverty than in 1990. Unemployment officially stands at 28 per cent and 36 per cent unofficially. It is a staggering 68 per cent among young people. Equally, Mandela’s idea of the rainbow as the narrative for nation-building and unity proved to be a disappointment. Its failure is rather extensive. The White hearts simply couldn’t purge racism and the backlash inevitably began.

The South African parliament voted in late February in favour of a motion seeking to change the constitution to allow White-owned land expropriation without compensation. Julius Malema, leader of the Marxist opposition party, who tabled the motion said, “The time for reconciliation is over. Now is the time for justice. We must ensure that we restore the dignity of our people without compensating the criminals who stole our land.” According to a 2017 government audit, White people own 72 per cent of farmland. The most productive, large-scale commercial farms in South Africa are almost all White-owned. It is a blot on Mandela’s legacy that despite the end of apartheid in the 1990s, the chasm between the wealthy elite and masses of workers and oppressed has only grown.

How did this happen? When the uprisings in Soweto and other Black townships began to make the country ungovernable by the early 1980s, the White ruling elite, with backing of Western powers, initiated negotiations for a peaceful end to apartheid and a formal transfer of power, with the aim of quelling the revolutionary challenge from below and preserving their wealth and property. From jail, Mandela was courted by leading corporate executives, who saw in him the best hope of politically defusing the situation. Mandela and the African National Congress (ANC) obliged. Mandela utilised his indubitable political skills and personal courage to stave off the threat of a social revolution, dismantling the apartheid regime while also defending capitalism and protecting the property and wealth of the country’s White rulers and of transnational corporate investors. Implicit in the compromise was an assurance that the property, wealth and commercial interests of both the White elite and international finance capital would be protected. Suffice to say, the end of apartheid saw the country’s people win the ability to vote and secure other democratic rights denied to them under apartheid rule, but it did not alter the fundamental division in society. The bitter reality is that the social position of the working class is worse than it was under apartheid.

Suffice to say, Mandela was not exactly the great revolutionary figure that Barack Obama wants us to believe, but actually had ended up making neoliberal deals and patronised a pro-business agenda. Indeed, that does not detract from his tremendous vision or moral courage. His symbolic significance is almost unique. But, alas, he didn’t fight poverty. And the resultant lack of accountability spawned rampant corruption and venality and opened up a serious gulf between the ANC and the mass of the population that brought it to power. African historian Achille Mbembe describes the ANC as a party “consumed by corruption and greed, brutal internecine battles for power and a deadly combination of predatory instincts and intellectual vacuity.”

The South African tragedy reminds us of India’s historic transition under Nehru’s progressive leadership. Like the ANC, the Indian National Congress was a bourgeois movement, but it could transform as a vehicle for realising the aspirations of the masses whom Gandhi brought into it because of the socialist ideology, which was almost entirely Nehru’s legacy to the freedom movement. In developing countries such as India and South Africa, political legitimacy is derived primarily from the sensitivity of the ruling elite toward the problem of poverty. In India, too, the Congress’ decline began once it moved away from the socialist ideology after the Nehru era.

A former ambassador