SHOCKING: Crime against women is etched in social mores. File photo

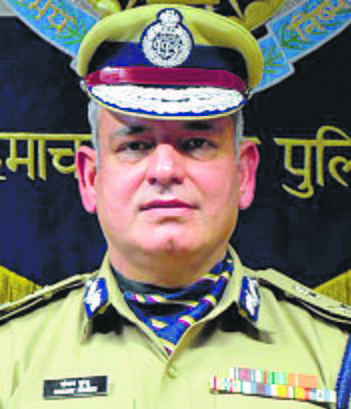

Sanjay Kundu

Director General of Police, Himachal Pradesh

No nation or society can progress unless violence against women is addressed and they feel free to live their lives as they choose. Peter Drucker, the famous management thinker, once said, “If you can’t measure it, you can’t improve it,” meaning you can’t possibly get better at something that you can’t measure. To be able to move ahead and abate all forms of violence against women, we need to be able to measure it with clearly established metrics and then address it by robust strategies, with success that can be defined and tracked, or else, we would be running blind plans.

The life cycle of violence against a woman starts in the family she is born in or the family she gets married into and then there are some external factors. The spectrum of this violence begins at its low end from coercion and arbitrary deprivation of liberty and moves on to serious crimes. With the entire gamut of this violence extending well beyond the physical, sexual or psychological harm, there is more to it than meets the eye. Though some violence is captured as crime under various criminal statutes, there are forms of violence for which hitherto there are no measurable metrics.

The criminal laws enacted during recent times have penalised some forms of violence against women, but the Punjab Police Rules, which govern day-to-day working of the police in the north Indian states, were framed circa 1930 to establish a system of policing to serve British imperial interests, with focus on control and surveillance to nip threats to the empire in the bud. Thus, the purpose of the police stations, police work and the system of crime records put in place through 25 police station registers was to control rather than serve. Mindful that these registers did not adequately catch violence against women, we took new initiative to start a few registers to capture all forms of violence against women and bring them on our radar.

As the station commander of a UN police station during the UN mission in Bosnia and Herzegovina, a country emerging out of post-conflict trauma, I was fortunate to work with police officers from over 50 countries and learn from their experience. One such discourse with a Miami police officer who was a career sex crime investigator is deeply etched in my mind. We got into a discussion about the two theories of sex crimes, namely, ‘sex drive and drive to possess and control’. He commented that sex crimes were about ‘sick mind’ or else, how would you explain the rape of a six-year-old girl or a 75-year-old woman and what sexual pleasure or powers were to be derived from such acts. He added that people who have ‘sick mind’ are likely to perpetrate such crimes again and again unless their mental sickness is dealt with.

Leading US police departments maintained a profile of all sexual offenders in their jurisdiction. I put this learning to practice and we introduced register number 26 for “offenders of crimes against women and children” in Himachal Pradesh. We accrued three distinct benefits of introducing this register. First, it has provided the much needed data on the quantum and profile of sexual offenders. Secondly, it is much easier to police these sexual offenders numbering in thousands than to secure 35 lakh women in the state. Thirdly, and most importantly, it has brought down violent crimes against women and children.

For every suspicious death of a woman, there are doubts, whether it is a homicide or suicide. Delving deeper into our data revealed that suicides, though high in numbers, never rang bells on our radar. Suicides can be classified largely into two categories. The first being pushed to commit suicide or ‘abetment to suicide’, covered under Section 306 of the IPC. The second is committing suicide of one’s own volition, dealt by the police as inquest procedure under Section 174 of the CrPC. While women constituted only 30% of the victims under Section 174 of the CrPC, they were 60% of the victims under Section 306 of the IPC, indicating that a large number of married women or young girls were pushed to commit suicide. To capture such suspicious deaths, we introduced register number 27 for ‘suicides’ in the police stations in two parts, capturing both (a) abetment to suicide under Section 306 IPC and (b) suicides under Section 174 of the CrPC. This register has helped us to maintain a reliable record of suspicious deaths, analyse their causes and intervene where they can be prevented.

Every year, we recovered several unidentified dead bodies (UIDBs), many of whom were of women. Apparently, some of these were subjected to violence before their death, but there was not much that we could do unless the bodies were identified. Determining their identity was essential, first to be able to investigate their cause of death and bring the perpetrators to justice. Secondly, we were obligated to give them an honourable funeral or leave their last rites to be performed by the municipal bodies or panchayats. We wrote to the UIDAI authorities to allow us limited biometric access of the UIDBs to enable us to determine their identity, but since the matter was

sub judice in the Supreme Court, they could not offer us help. Then, there is the issue of missing women and children, who need to be traced post-haste, or else, are likely to be abused and exploited on account of their vulnerability. To meet

both these objectives, we started register number 28, in two parts: (a) register of unidentified dead bodies; (b) register of missing women and children. This register has facilitated in keeping track and managing the hitherto unreported and unmeasured aggravated forms of violence against women.

We have moved the wheels of time past where the British left them in 1930s and tried to capture and measure all possible forms of violence against women. However, it is still work in progress, with the rise of offensive sexual content across the cyber-space posing a new challenge. It will take a while to reliably measure this emerging crime till both the technology and the profile of crime stabilise. As Ban Ki-moon, the former Secretary General of the UN, said, “There is one universal truth, applicable to all countries, cultures and communities: violence against women is never acceptable, never excusable, never tolerable.” Let us work to make that happen and as a first step in this direction, reliably measure the violence and then deal with the problem.

Join Whatsapp Channel of The Tribune for latest updates.