KC Singh

PRIME Minister Narendra Modi returned from his carefully crafted foreign trip at the end of September, combining a stopover in Ireland, address at the UN Special Session on sustainable development and Californian theatre, mixing high technology wooing with the usual diaspora hoopla. He avoided assiduously meaningful contact with the Pakistan delegation led by PM Nawaz Sharif.

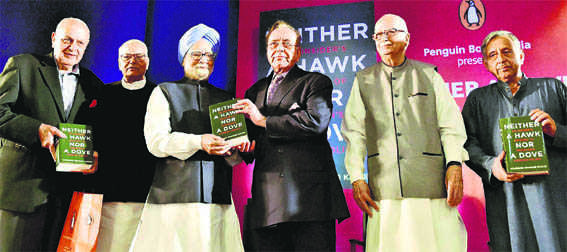

Awaiting him on his return were not only the crucial Bihar polls but Khurshid Mahmud Kasuri, former foreign minister of Pakistan, with his book “Neither a Hawk Nor a Dove”, propelling Pakistan in news. This 800-page tome, overpriced at Rs 999, has flashes of new material, largely falling victim to standard Pakistani formulations on terror, nuclear proliferation, Sino-Pak relations as indeed ties with India. Its main contribution is in giving a more intimate account of the back-channel attempt to resolve the Kashmir issue over many years by personal envoys of President Pervez Musharraf and Indian Prime Ministers AB Vajpayee and Manmohan Singh.

The drama would have faded after the book’s Delhi release had not the intemperate Shiv Sena, despite its ally the BJP authorising the author’s visa, turned the book’s Mumbai function into a slugfest. The issue fuelled an already simmering resentment, over multiple episodes of cultural censorship by fringe elements belonging to the BJP or its allies, into a full-blown national debate on freedom of expression. Writers in droves have lined up to return Sahitya Akademi awards expressing solidarity with the cause.

The book throws light on some events that have otherwise not been fully explicable. For instance, the Anti-Terror Mechanism announced in 2006, post train bombings in Mumbai that had stalled bilateral dialogue, was suggested by Indian High Commissioner SS Menon to the office of Musharraf. It was an Indian methodology to overcome the hurdle created by the monstrous terror act and not a Pakistani concession. Similarly, Musharraf’s address to the UN General Assembly in 2005 that contained harsh rhetoric on Kashmir and spoilt the bonhomie preceding it was due to the speech having been left to Pakistan’s hawkish PR to the UN to draft. It was not reviewed in advance by either the minister or Musharraf’s office. Sounds unbelievable, but sometimes facts can be stranger than fiction.

The two other critical points the book addresses are the eight subjects in the existing composite dialogue and the proposal that was evolved to settle the Kashmir issue via the back-channel by special envoys meeting surreptitiously over many years till Musharraf’s downfall in 2007.

The critical flaw in the dialogue’s structure is that the eight sub-headings contain disputes and confidence-building measures (CBMs). Historically, the latter are supposed to create the environment for the settlement of the former. These are economic and commercial cooperation, promotion of friendly exchanges in various fields, maintenance of peace across the LoC, water projects, etc. After all, if all disputes are resolved, why would you need CBMs? Unfortunately, Kasuri subscribes to the standard Pakistani argument that the more intricate the dispute i.e. Kashmir, the earliest it must be settled. Implication being that otherwise Pakistan will drag its feet in uprooting the India specific terror network or implementing CBMs.

The disputes are: Kashmir, Siachen and Sir Creek. Intertwined with these are terrorism, drug trafficking and steps to obtain strategic stability in the nuclear and conventional fields. All these need examination.

Kasuri makes the fallacious comparison that just as India unilaterally occupied the Siachen glacier in the 1980s, Pakistan intruded in the Kargil region in 1999. He ignores that while Pakistani forces crossed an established de facto boundary called the LoC, to which the Simla Agreement gives sanctity, the Siachen glacier was beyond NJ9842 — the last point demarcated on the 1949 Ceasefire Line settled by the Karachi Agreement. Sir Creek is probably mature for settlement, but each side hopes to link it to some other concession. Until that is settled, the maritime boundary between the two countries remains unsettled leading to periodic arrest of fishermen by either side.

It is on Kashmir that the book reveals the chronology of back-channel diplomacy to make the LoC irrelevant, while maintaining status quo territorially, proposing demilitarisation, autonomy given by each side to portions of Kashmir they control, self-governance and finally a joint mechanism. Points of interest are that on Indian insistence Pakistan conceded that Gilgit Baltistan would be a part of the settlement. India too conceded simultaneous demilitarisation, whereas even the 1948 UNSC resolutions make it incumbent on Pakistan to fully withdraw its forces, while India is required to only downsize them. The still unsettled issue was of joint mechanism i.e. how much of control to be shared by India and Pakistan. Whether this could have been sold to the Indian Parliament and public shall remain moot as the Musharraf government fell in 2007. Interestingly, on the Pakistan side each foray by their envoy was followed by a proper civil-military review over which Musharraf presided. Among those who attended were the DG ISI and the vice-chief of army staff. It is unknown who, if any, were on board on the Indian side.

Regrettably, for a man of Kasuri’s stature, there is not a word about Lashkar-e-Taiba, their role in conducting the 26/11 operation in Mumbai, the protection extended to them by successive governments in Punjab. Pakistan army, he concludes, is not driven by permanent enmity towards India. It is merely seeking “permanent security”, as it recognises that peace with India is a condition precedent to Pakistan resolving its complex socio-economic and religious issues. However he reverts to the slogan “peace with honour”. He underestimates the growing power differential between India and Pakistan, particularly the growth paths of their respective economies.

Hopefully, he does not carry the wrong message from his Indian experience. Fate of India was not settled by an ink-smudged Sudhendra Kulkarni, however, important his issue. It was being shaped by ordinary Indians casting exactly then ballots in Bihar, also seeking peace with honour.

— The writer is a former Secretary, Ministry of External Affairs