Wooden khamba slabs installed near the road between Uchhal and Nizar

BN Goswamy

No one recognises the richness of their (the tribals’) rituals, the great power of being possessed by God, the intensity of belief, even the beauty of dancing, or being in a trance, as cultural values.

— Eberhard Fischer & Haku Shah

Lodha dev, lakda dev, tamba rupa dev, chhana dev, mena dev

Mena dev kal dharti, dev mogra, dharma dharti, helu pandar, dev mogi, puja padase

(God of iron, god from wood, god of copper, god from cow-dung,

Black earth, god crocodile, sacred earth, cold queen, goddess crocodile:

Please accept our worship)

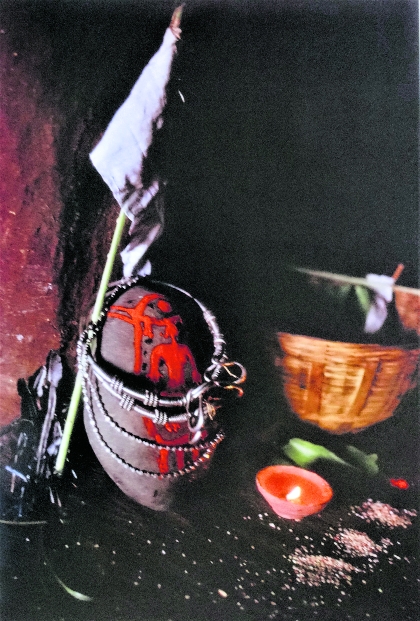

— Tribal song sung at the time of installing a crocodile-god’s image

There is a popular Bengali saying that runs, ‘Baans baney dom kaana’: meaning, ‘in a forest of bamboos, the bamboo-cutter goes nearly blind’. Because there is far too much to choose from. This is the feeling that washes over one when one sees — ‘encounters’ might be a better term — a work like Eberhard Fischer and Haku Shah’s ‘newest’ book, ‘Art for Tribal Rituals in South Gujarat, India’. The sub-title says that it is not so new, for it runs, ‘A Visual Anthropological Survey of 1969’. But there is so much in it, so much freshness, such sharp detail, that it seems hard to believe that all that is in there goes back some 50 years or so. Arriving as they did as young men — one affiliated to the University of Heidelberg in Germany, and the other to the Tribal Research and Training Institute at Gujarat Vidyapith in Ahmedabad — in that remote corner of Gujarat in 1969, the two did not only see everything with fresh and eager eyes, but now make us see it all that through their eyes.

As one reads chapter after chapter, one feels as if one is moving with them through remote villages, treading untrod paths, climbing hillocks and negotiating brush, locating informants and interviewing people, sipping tea sitting inside thatched huts, sleeping under the sky, measuring objects, watching death rituals and spiritual healing, hearing songs and registering rhythmic beats, circumambulating sites, observing icons being carved: and photographing, photographing, photographing all the time. All this was during the day, however. At night it was time to put scribbled notes in order, and type them out.

Even a quick look at the chapter headings sends one thinking. The two researchers – Eberhard Fischer as a trained anthropologist who had worked earlier with tribal art and culture in Africa and had been close to the iconic teacher, Alfred Buhler; and Haku Shah, as one deeply rooted in Gujarati culture and immersed in the study of tribal arts — began with describing the land and people of the former Surat district. And then they moved with consummate ease into the life and beliefs of the ‘tribals’ – the term is now hardly ever heard, having been replaced very carefully with ‘Adivasi’ — inquiring into their knowledge of ‘Supernatural and Divine Powers’ , of the ‘Human soul and the spirits of the Dead’; delving into the world of the ‘Bhagats’ who are specialists for rituals, oracles, and healing; watching terracotta horses being offered to Himariya dev and the dana Oracle; witnessing the whispered world of ‘Death and contacts with the Dead’.

the open.

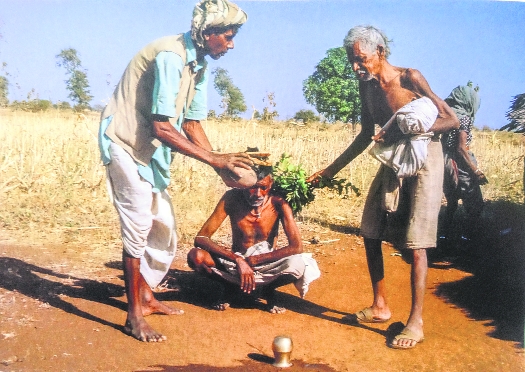

With great interest — one has to recall that Fischer is an art historian, apart from being an anthropologist – the two observed, step by step, cut by cut, the making of Icons for the Dead, including the soul-stone, Khatru; the wooden vetra figures with sculpted heads; the Khamba (pillars) and the stone memorial slabs. The highly revered wooden Mogra dev — crocodile deity — swung into their view, and sacred sites were explored. But all the goings-on in the life of the tribals were not only recorded in verbal terms: one can see it as having been visually documented. So densely is this done in fact that as one moves from one page to the next, the sensation one gets is of looking at a sheaf of a photographer’s contact sheets.

Nothing was done, as Fischer and Shah proceeded, in a hit-or-miss manner. A firm and clear ‘ethnographic’ pattern was followed as far as approaching the subject and the people were concerned. They stated this at the very beginning. “First of all,” as they planned, “only our own visual and auditory experiences will be recorded”; the attempt was “to relate our experiences objectively, in simple language, not allowing personal feelings to influence us in any way”; intentionally “a sparse expression of words” was adopted. What was avoided was “working on already existing literature to make comparisons with findings from other areas”. If one reads and sees the material finally presented in the work, one can see that this ‘protocol’ was strictly followed. There is no judgemental slant in how or what they recorded; there were no ‘opinions’ or recommendations; there was not even the slightest inflexion of superiority.

On the other hand it is all out there: up front and transparent. If anything, there is the warmth of humanity here: in the portraits of men and women, in the sympathy with which death rituals are recorded; in the respect accorded to their beliefs and regard for their aesthetics. One can see this in the pictures: joy in the springy steps of young maidens as they make their way to the village fair; solemnity in the occasions when bodies are being readied for final rites; total absorption when it comes to the work of the craftsmen; breathlessness and beauty in the steps of the dancers.

There are great riches on offer in this volume, and one cannot but be astonished at the manner in which it has survived – text and pictures and thoughts – for close to half a century. For me, what emerges from its study is not only the documentation, the facts: it is respect for the innate wisdom reflected in the life-style and beliefs of the people whose lives and practices were studied and documented. A respect also for what we call ‘saadagi’. The word means more than ‘simplicity’, for wrapped in its layers somewhere are also notions of ‘honesty,’ ‘transparency’, ‘truth’.

Join Whatsapp Channel of The Tribune for latest updates.