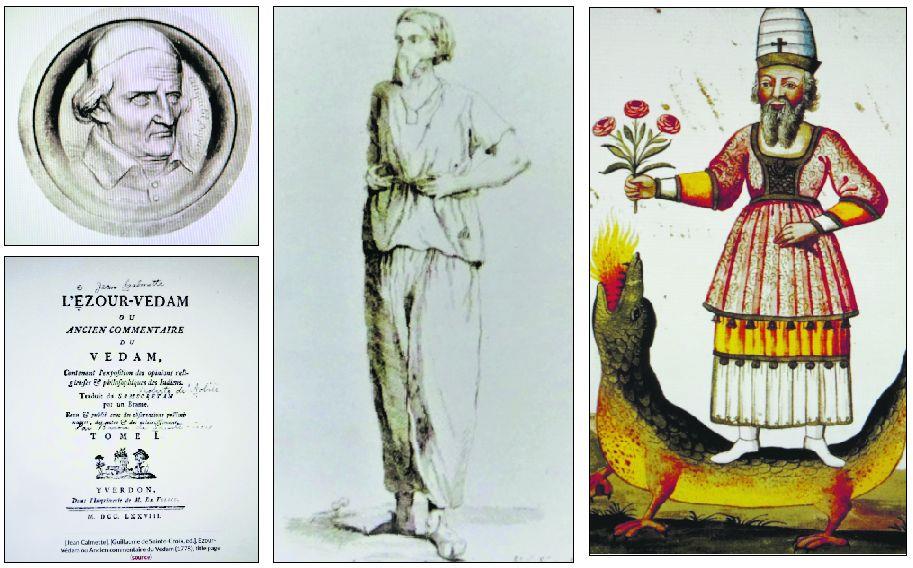

(Clockwise from extreme left) An early translation of the Vedas from Sanskrit. Published in 1778 in France; medal with image of Anquetil-Duperron. Design by David d’Angers. France, ca. 1850; a Parsi gentleman wearing the girdle, kasti. From a book published by Anquetil-Duperron; an imaginative rendering of the prophet Zoroaster (Zarathustra), founder of Zoroastrianism.

BN Goswamy

If the red slayer think he slays,

Or if the slain think he is slain.

They know not well the subtle ways

I keep, and pass, and turn again.

— from the poem ‘Brahma’ by Ralph Emerson, ca. 1840

The Upanishads are the production of the highest human wisdom and I consider them almost superhuman in conception… From every sentence of the Upanishads, deep, original and sublime thoughts arise, and the whole is pervaded by a high and holy and earnest spirit. In the whole world there is no study so beneficial and so elevating as that of the Upanishads.

— Arthur Schopenhauer, German philosopher, ca. 1820

VIRTUALLY unknown to most of us now — if not exactly that, at least virtually forgotten — a French linguist and scholar, Anquetil-Duperron (1731-1805) by name, was drawn in the most curious of manners to India and her literary/religious heritage. A Professor of Arabic in Paris called the attention of this young man to four folios in facsimile of a manuscript which had come into the possession of the Bodleian Library in Oxford, but such as nobody could read them. The script was simply not recognised. Using his imagination, therefore, the librarian placed the manuscript in a box chained to a wall near the entrance, which was shown to ‘everyone who might be able to identify the curiosity’.

It was a part of a version of Avesta, the sacred book of Zoroastrianism, and Anquetil — the full name is Abraham Hyacinthe Anquetil-Duperron — thought he could recognise it through a transliteration table that had somehow come into his hands. His mind was quickly made up: he would travel to India. Behind his resolve was not only intellectual curiosity and challenge, but also, one can be certain, the thought of doing better than the British with whom the French were in serious competition then, both militarily and intellectually.

For going to India, Anquetil enlisted himself as a common soldier in the French East India Company, arriving at the French colony in Pondicherry in August 1755. He was treated especially well on the ship since a minister in France had recognised in him a seeker, a man who wanted to immerse himself in learning about the East and its treasures. After that, his life reads like a romance, filled with adventures, friendships and betrayals, for he was everywhere, travelling from the south to Chandernagore, another French possession, in Bengal; making his way to Benares to learn Sanskrit; and ending up in 1758 at Surat.

There are mixed accounts of him, and the authenticity of his claims and memoirs has often been questioned, especially by the British, who saw him as a rival. One thing is certain though: at Surat, he stayed for long years, devoting himself mostly to learning about the sacred Avesta from Persian-knowing Zoroastrian priests and tutors. One Darabji is especially mentioned because it was a manuscript of the Avesta with him that Anquetil wanted to translate, after having learnt the text. The relations between him and his tutors did not always remain on an even keel, however. On the one hand there are accounts of serious confrontations between them and, on the other, there was talk even of his receiving a kasti and a sadra — a girdle and a jacket, de rigueur symbols of Parsi wear — and his being allowed entry into a fire temple on one occasion. Whatever the case, after his long period of stay in Surat, then the centre of Zoroastrianism in India, Anquetil sent news to Paris that he had completed his translation of Avesta in Latin. It is widely recognised that it was with this translation of the Avesta that the Western scholarship of Zoroastrianism began.

There was fame round the corner for him. Before he left Surat, he had collected 180 manuscripts that included many works of the Zoroastrian tradition. The translation of the Avesta was finished in 1760, and, as he declared, his mission of going to India to ‘discover and translate the works attributed to Zoroaster’ had been achieved. He returned to Europe, visited Oxford, and deposited the manuscripts he had brought from India into the Royal Library. The report he had prepared of his visit to India and his work was published in 1762. He had become a celebrity and honours, including an appreciation by Voltaire, the great philosopher, became almost a routine. “Nothing thwarted his courage,” Voltaire wrote of Anquetil once: “not sickness, not wars, not the obstacles that appeared at every step.” There were accusations, of course, and scorn poured on his work by rivals, like Sir William Jones, the rising Orientalist star of British India. But his publications never stopped. In 1771 was published his three-part Zend-Avesta: works attributed to Zoroaster.

But there was more to come from Anquetil. His “most valuable achievement”, as it has been described, was the publication of a two-volume translation, in Latin and French, of 50 Upanishads that he had received from India. Among the finest philosophical/religious works ever composed, these Upanishads had been translated more than a century earlier by the Mughal prince, Dara Shikoh, into Persian from Sanskrit, and it is these translations that now formed the basis of Anquetil’s own translated work. He published them under the title Oupnek’hat — a slightly corrupted version of the word Upanishad — and when they appeared — the first European language translation of ‘a Hindu text’ — from Strasbourg in 1801-02, they caused a sensation. What followed is history, so to speak, and the number of scholars, worldwide, who read and held them in veneration — Thoreau, Emerson, Walt Whitman, Max Mueller, among them — is a legion. Schopenhauer’s words keep ringing in the air: “The Upanishads have been the solace of my life and will be the solace of my death,” he wrote. Ex Oriente Lux: Light coming from the East.

One remembers Anquetil-Duperron only a little today, certainly in our land. But at least the library of the famed Institut Français de Pondichéry is named after him.

Join Whatsapp Channel of The Tribune for latest updates.