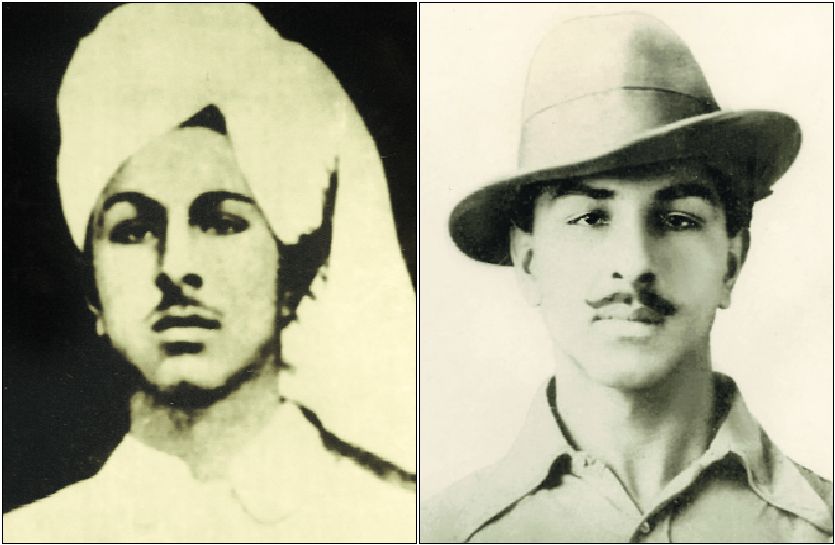

This black-and-white picture (left), which endears him to fellow Sikhs and Punjabis worldwide, is a key element of Bhagat Singh’s iconography. It is vastly different from his more popular, prim-and-proper look: wearing a felt hat, with a twirled moustache.

A man with beliefs and ideals like mine could never think of dying uselessly. We want to get the maximum value for our lives. We want to serve humanity as much as possible. —Bhagat Singh, Letter to Sukhdev against suicide, 1929

Vikramdeep Johal

Bhagat Singh was one among several Indian revolutionaries who were martyred in the prime of their youth. He and his comrades Rajguru, Sukhdev, Jatin Das and Chandra Shekhar Azad were in their early or mid-20s when they made the supreme sacrifice. Bhagat Singh’s own idol, Kartar Singh Sarabha, was just 19 when he was executed in 1915. All of them deserve to shine in our collective memory as bright young stars for all eternity. What then has made Bhagat Singh the first among equals? Why is he easily the most celebrated and venerated of the lot?

Read also: Satvinder Singh Juss on the farcical trial of Bhagat Singh

Bhagat Singh, Sukhdev and Rajguru.

His face has launched a thousand campaigns. His name reverberates at virtually every protest; there is hardly a political party or government that fails to invoke him, especially during the election season. Here is an icon recognised and admired even by those who have never read his insightful writings or assimilated his thoughts. Indeed, it’s tempting to quickly co-opt Bhagat Singh rather than to slowly understand him. So overpowering and dazzling is the iconography surrounding him that at times it blinds us to the larger picture — there is much more to Bhagat Singh than meets the eye. But first, we need to delve deep into his visual reservoir. For the record, only four genuine photographs of Bhagat Singh are available. The other images are mostly reproductions or recreations, with not many of them being true to the originals.

The turban and the hat

“Medium height; thin oval face; fair complexion; slightly pock-pitted; aquiline nose; bright eyes; small beard and moustache; wears khaddar.” This is how the Criminal Intelligence Department (CID) described Bhagat Singh in its report in 1926. The busy teenager was on the CID’s radar for several reasons: he had served food to Jaito Morcha activists in 1924, for which he was booked under the Criminal Law Amendment Act; he was involved in an agitation spearheaded by the Zamindar Sabha against the hike in canal water rates; and he had performed in a play with a telltale title, ‘Bharat Durdasha’, which was staged by the Dramatics Club of National College, Lahore, on the sidelines of a Congress conference at Gujranwala in October 1925. It was along with other members of his college club that Bhagat Singh posed for a photo, sporting a pencil moustache with an incipient beard, and a loosely tied turban with its end perched on his left shoulder. His close-up, extracted from the group photo, was first published by The Tribune on the front page of the edition dated April 13, 1929, just five days after his arrest in the Delhi Assembly Bomb Case. In a striking coincidence, the then Lahore-based newspaper’s readers came ‘face to face’ with the young revolutionary on the 10th anniversary of the Jallianwala Bagh massacre, a monumental tragedy that left an indelible impression on Bhagat Singh and shaped the course of his short but eventful life.

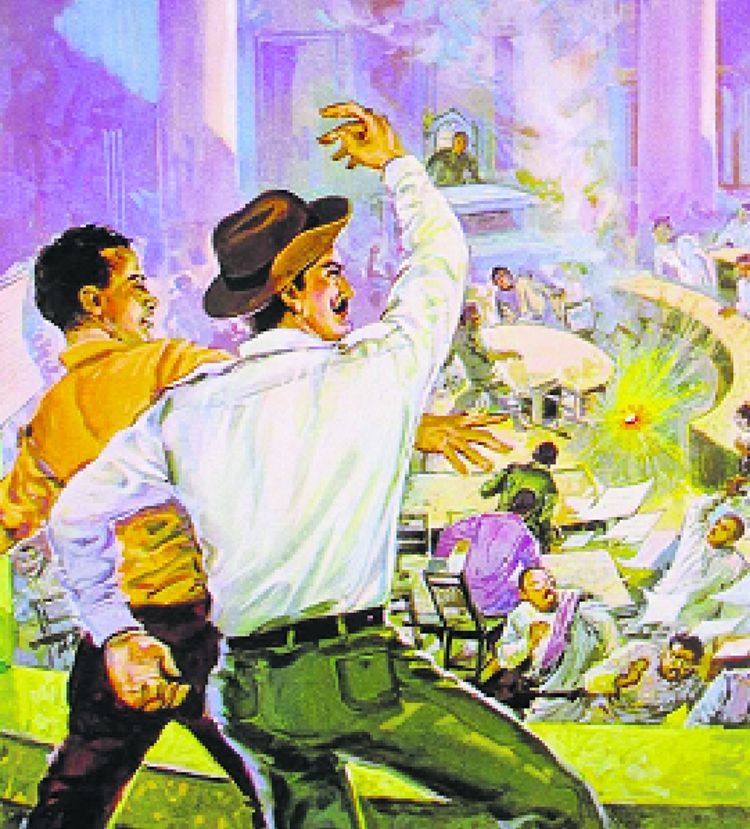

This black-and-white picture, which endears him to fellow Sikhs and Punjabis worldwide and has inspired countless, often inaccurate, portraits in colour, is a key element of Bhagat Singh’s iconography. It is vastly different from his more popular, prim-and-proper look: wearing a felt hat, slightly askew, with a nicely twirled moustache on a smooth and beardless face. This western avatar was created by him in the run-up to the Delhi Legislative Assembly incident (April 8, 1929), wherein he and Batukeshwar Dutt hurled country-made, low-intensity bombs with the aim of “making the deaf hear” in the highest echelons of power. He had already got his hair cut and beard shaved off in September 1928 in an attempt to hoodwink the police and ensure that he could travel unhindered.

The hat photo was taken on April 3 or 4 in the studio of Ramnath Photographers at Kashmere Gate, Delhi. “It is a fairly conventional studio portrait,” writes Kama Maclean, the author of ‘A Revolutionary History of Interwar India’ (2015). “He stares calmly into the camera, as if to defy the empire and the weighty charges about to be brought against him, namely, that he had been engaged in a conspiracy to wage a war against his Majesty, the King Emperor...”

According to her, “By posing for his photograph, Bhagat Singh was providing a pivotal ingredient for a publicity campaign that created a powerful movement around his pending martyrdom. The press was vital in spreading images of this and other photographs of revolutionaries that brought their politics to life.”

So ubiquitous is the hat image that it is compared to Cuban photographer Alberto Korda’s iconic picture (‘Guerrillero Heroico’ or heroic guerrilla fighter) of Argentine Marxist revolutionary Che Guevara. “Both were photogenic, capturing the romance, idealism and sacrifices demanded of the revolutionary. Both photographs, too, have been so widely appropriated that they have become disconnected from their historical context,” observes Maclean, a Professor of South Asian History at the University of Heidelberg, Germany.

Beyond barriers

The hat picture (and to a great extent the turban one) enjoys amazing visibility in the physical domain — from T-shirts, car stickers and tattoos to paintings, posters and hoardings — as well as in cyberspace, with social media amplifying the legend to the hilt. Cinema has done its bit with the classic ‘Shaheed’ (1965) and a mixed bag of films released in the 2000s, including ‘Rang De Basanti’. The Amar Chitra Katha picture book (1981), illustrated by Dilip Kadam, has introduced children of one generation after another to the great patriot. It was inevitable that Bhagat Singh’s face would pop up at the ongoing farmers’ agitation, which has also resurrected his uncle Ajit Singh, a rebel in his own right and the torchbearer of the Pagdi Sambhal Jatta movement of 1907 that mobilised the peasantry to fight for its rights.

There is another photo, intriguing but widely used nonetheless. It shows a bearded, handcuffed Bhagat Singh sitting on a cot, in conversation with an elderly man. At a cursory glance, it appears that he is simply chatting with an avuncular acquaintance or even a family member who has come to meet him in prison. Malwinder Jit Singh Waraich, a leading chronicler of India’s revolutionary history, throws light on this image: “It was taken secretly by the police at Lahore railway police station during Bhagat Singh’s first term in jail (May 29 to July 4, 1927). He had been arrested in connection with the Lahore Dasehra Bomb Case of October 1926. The person talking to him is Gopal Singh Pannu, DSP, CID, an old hand at interrogating revolutionaries since he was an investigator during the Ghadarite trials in 1915-16 as well.”

Unkempt hair, bare feet crossing each other: Bhagat Singh seems quite relaxed here. There is no visible sign of the tension one expects when a prisoner is being interrogated by a seasoned cop. Unaware of the camera, the young man appears to be handling the situation with sangfroid far beyond his 19-odd years. Waraich says the obvious purpose of clicking the photograph was to make copies and spread them around in the region so that it could be easier to keep tabs on him in view of his “known mobility and ubiquity”. The least circulated of the preciously few Bhagat Singh photos is the one clicked in his childhood: it shows a smartly dressed, turbaned boy, facing the camera with confidence.

Bhagat Singh’s compelling iconography might have granted him a legendary status that transcends all barriers, but it has also contributed to his straitjacketing as a nationalist hero and a martyr. S Irfan Habib, an eminent historian who has edited ‘Inquilab: Bhagat Singh on Religion & Revolution’ (2018), laments the neglect of the revolutionary’s intellectual legacy. “Bhagat Singh going to the gallows as a nationalist is not something exclusive to him alone; two others were hanged with him and many more were hanged before him as nationalists. He is different because he left behind a huge collection of political and social writings on burning issues of even contemporary importance like caste, communalism, language and politics.”

Bhagat Singh’s ultimate battle was not against oppressive colonial forces; it was against injustice and inequality. “Revolution (inquilab) is not a culture of bomb and pistol. Our meaning of revolution is to change the present conditions, which are based on manifest injustice,” he proclaimed in a joint statement. Ninety years have passed since his death, but his social and political vision continues to be obscured by shallow and hollow idolisation. A holistic understanding and appreciation of Bhagat Singh will remain elusive unless we start exploring what lies behind his omnipresent, overwhelming visage.

Portrait of the hero’s hero

Immortalised in his imagery over the past nine decades, Bhagat Singh himself believed strongly in the power and reach of the visual medium. In his memoir, ‘Amar Shaheedon Ki Yaadein’, Raja Ram Shastri writes: “Bhagat Singh always strived to attract the attention of the youth towards the lives and deeds of the martyrs. He collected their photographs, wrote brief life sketches and got them published in magazines like ‘Kirti’ and ‘Chand’. He also got slides made to be projected by a magic lantern at public gatherings. Of all the martyrs, Kartar Singh Sarabha was his role model.”

Shastri came in touch with Bhagat Singh and other knowledge-hungry youngsters during his tenure as the librarian of Lahore’s Dwarka Das Library (based in Chandigarh since 1966), founded by Lala Lajpat Rai in 1920. The latter’s death was avenged by Bhagat Singh and his comrades with the murder of British police officer JP Saunders in 1928.

A photo of Sarabha was found during a search at Bhagat Singh’s house in Lahore after his arrest in Delhi. He, however, did not confine himself to mere idol worship; he not only emulated the Ghadar martyr, but became a towering role model himself.

Join Whatsapp Channel of The Tribune for latest updates.