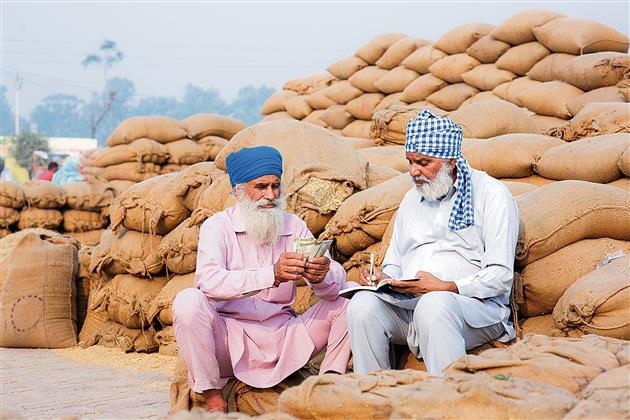

It remains to be seen how the Direct Benefit Transfer (DBT) system will change the dynamics of the farmer-arhtiya relationship. istock

Ranjit Powar

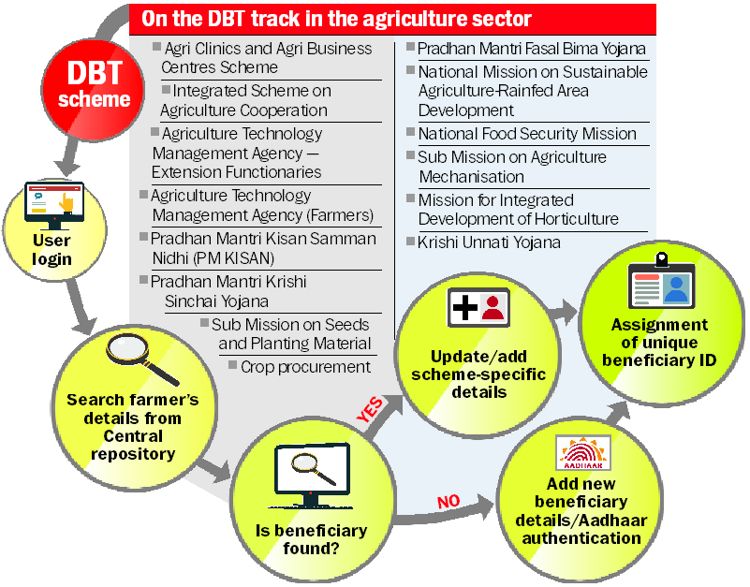

AT the Centre’s insistence, Punjab has finally started making direct payments to farmers for their produce under the Direct Benefit Transfer (DBT) mode during the ongoing wheat procurement season. Other states are already implementing this system, even as Punjab had been keen to route the payments through the arhtiyas (commission agents), as per the long-established practice. The arhtiyas in Punjab and Haryana initially registered a protest by proceeding on strike, but they relented after the state governments promised to safeguard their interests. Earlier attempts to introduce DBT had been resisted and were eventually shelved. Hopefully, DBT is now here to stay, reducing delays in payment to the farmer and letting him receive his earnings directly.

Much has been said about the close-knit relationship between the farmer and the arhtiya. The arhtiyas insist that implementing the DBT will ‘destroy’ the farmer. It remains to be seen how the new system will change the dynamics of the farmer-arhtiya ties.

Why this resistance to DBT by the arhtiyas, and why have successive governments in Punjab been silent connivers? What is the normative role of commission agents in any business? The arhtiya is a mere facilitator of the transaction between the farmer and the Food Corporation of India (FCI) or a private trader. He has absolutely no claim to the farmer’s land or grain. Why, then, was he entitled to receive payment on the farmers’ behalf?

The arhtiyas in Punjab are paid a commission of 2.5 per cent (among the highest in the country) for their services during procurement, including handling and cleaning of the farmers’ grain when it arrives in the mandi, filling it in bags, weighing, stitching and subsequently loading the bags into trucks for despatch. They play an essential role in one of the most extensive government operations in Punjab, a predominantly agricultural state. Nevertheless, is it restricted to the official brief, or does it include a concealed, unkosher agenda?

In addition to his officially designated duties, the arhtiya is also the modern-day moneylender, financing the farmer in times of need at interest rates ranging from 18 per cent to 37 per cent. The Punjab Government acknowledges the arhtiya as being the ‘ATM’ of the farmers! Do other businesses withdraw money from the ATM at an interest rate of 37 per cent? Why is the farmer forced to turn to the arhtiya to borrow money at exorbitant rates, pledging his earnings as collateral? Why is the farmer driven to self-destruction through such borrowings? Why have successive state governments played along with this exploitative system? Are cooperative banks set up to give easy access to credit at modest rates in rural areas defunct?

Let us open this can of worms. The farmer brings his crop to the mandi yard, from where the arhtiya takes over. The crop is weighed and cleaned (often inadequately). It is put up for auction, bought either by a government agency at the Minimum Support Price (MSP) or a private trader. The arhtiya’s multi-pronged rapport with the purchase inspector is a major contributing factor that determines whether or not the grain qualifies for MSP. The purchased grain is next filled up in jute bags (often in the late evening when the farmer is absent) with a considerable error margin. In keeping with the rates of the parallel economy operating in the grain yard, a certain amount per bag is reportedly paid to the inspector of the purchasing agency, which is further said to be shared with a section of district and state-level administrative functionaries.

The uneducated or semi-educated farmer feels incapable of dealing with the inspectors and relies on the ‘skilful’ arhtiya to sell his grain. He turns to borrowing money from the arhtiya at high rates because the banks usually do not help him get loans. For him the arhtiya is a necessary evil because there is a trust deficit and general lack of honest handling by state agencies.

Exploitative side business

The arhtiya insists on the farmer’s payment to be routed through him to be able to deduct his loans. Is the government pledged to cover the risk for his exploitative side business? There is some give-and-take here. The arhtiya is also the conduit for deducting the payoffs for the purchase agencies from the farmer’s payment check. Thus, all beneficiaries from the farmer’s earnings want to keep the system going to safeguard their share. The farmer, with no solid lobbies or effective organisations, has been the ultimate victim.

A conversation with some farmers after the implementation of the DBT system has revealed that the arhtiyas insist on receiving signed blank checks from the farmers before auctioning their produce. Haryana has reassured the arhtiyas that they would be duly intimated one day prior to the disbursal of payment!

Restrict arhtiyas’ role

Not surprisingly, a large number of commission agencies are owned by local politicians. It is a no-loss business with an assured income through two-three months’ work in a year. Though the arhtiyas are essential functionaries in the grain procurement process, their role needs to be restricted to official limits. The financial dynamics of the procurement system must be restructured in favour of the farmers, not of those exploiting him. Instead of unabashedly lauding the arhtiya as the ‘ATM’ of the farmers, let the state government activate ATMs where they should be — in the rural banks. Politicians and procurement agencies should clean up their Augean stables. DBT might change the scenario only if the state government genuinely works to safeguard the interests of the farmers.

The author retired as Deputy Director, Department of Food and Civil Supplies, Punjab

Join Whatsapp Channel of The Tribune for latest updates.