Rough times ahead: Those considered well educated even 20 years ago are struggling to find jobs today. Photos: Agencies

Shiv Kumar in Mumbai

Neither long hours meandering through Mumbai’s jammed traffic nor the frustrating wait in front of tiny restaurants seems to daunt Umesh Somappa as much as the fear of getting a rating of three star or lower from a disgruntled customer. Somappa, a delivery boy for Zomato, frets over reduced incentives and even loss of the job every time he runs into a sulking customer.

“Sometimes I earn as much as Rs 30,000 per month, including tips and incentives,” says the 34-year old, who took up this job after a series of gigs over the past 17 years. An ITI-trained fitter, Somappa’s last job was with an industrial unit in suburban Mumbai which downed shutters shortly after demonetisation. “The factory closed down after demonetisation. The building where the unit was located is being redeveloped into a residential tower,” he says while lounging around between orders.

A casual chat with Somappa’s colleagues, who are fussing over orders on the Ramzan Eid holiday, shows many of them have been through periods of unemployment over the past few years. The jobs they held in the past few years vary from factory hands, shop assistants, courier boys, and even office boys.

Almost all of them are vaguely aware of the benefits like paid leave, provident fund and medical reimbursement that come with a formal job. “It is a matter of destiny for one to get a good government job,” says Somappa as his friends nod.

With manufacturing units in Mumbai shutting down, there are fewer opportunities for young men like Somappa who are classified as skilled workers. “Business has been down for small-scale industrial units following demonetisation and the introduction of the GST,” says Animesh Bhatacharya, who owns a metal working unit in suburban Mumbai.

Many of these units survived by carrying out job work for bigger units and were paid in cash. According to analysts, small scale units mainly survived because their margins came from evading taxes.

“I have given my three galas (as factory premises are called in Mumbai) on rent,” says Bhatacharya. His tenants are logistics companies who use the premises as store houses. A handful of semi-literate loaders are employed on daily wages in a factory, which employed 60 persons three years ago.

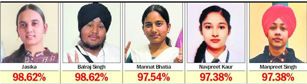

With not enough recruitment by the government and the corporate sector demanding high levels of educational qualifications, those who were considered well educated even 20 years ago are struggling to find jobs.

Subhash Gaikwad (23) is unable to find a job despite scoring a First Class in the B.Com examination two years ago. After rejecting sundry office jobs which paid barely Rs 15,000 per month, Gaikwad is planning to sign up for an MBA course.

Recently the Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy (CMIE), a Mumbai-based think-tank, released a report which stated that the unemployment rate was actually much higher than that claimed by the government. From 7.66 per cent in 2017, unemployment rose to 9.35 per cent in April 2019, CMIE said in its report.

Worse still, according to CMIE, joblessness among graduates was 17 per cent — almost double the general unemployment rate. Reports say around 1.1 crore graduates and another 2.2 crore undergraduates who have completed Classes X and XII form most of the unemployed people.