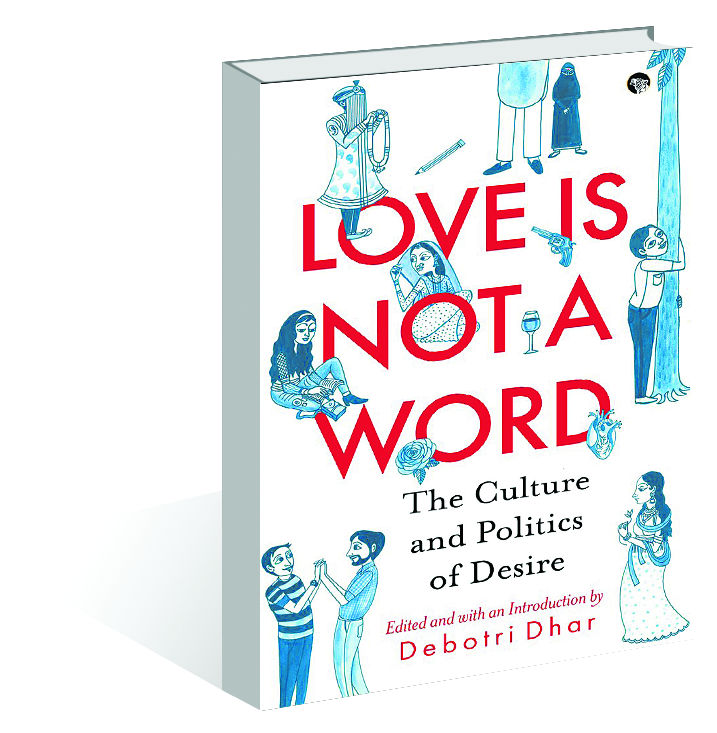

Love Is Not A Word: The Culture and Politics of Desire Edited by Debotri Dhar. Speaking Tiger. Pages 210. Rs294 (Kindle)

Book Title: Love Is Not A Word: The Culture and Politics of Desire

Author: Debotri Dhar

Aradhika Sharma

The author’s argument is that love is not only a poetic matter but, from many angles, a matter of politics of gender, race, religion, role, narrative... Towards this, she has chosen 12 essays by leading authors, from within and out of India, who have delved into the rich resources provided by works like Vatsyayan’s Kamasutra, Ghalib’s love poetry, the epics Mahabharata and Ramayana, Bollywood films and even internet dating sites. The essays of love, written, amongst others, by Makarand Paranjape, Alka Pande, Malashri Lal, Mehr Afshan Farooqi and Rakhshanda Jalil are sometimes personal, sometimes scholarly, and she is successful in presenting a compendium of various perspectives of love.

In the first essay in this collection, Swayamvara, Arranged Marriage, and Desi Romance, Malashri Lal questions the norms that assume the powerlessness of women regarding choice in love and marriages. This defies the ancient practice of swayamvara which transitioned into the present-day arranged marriage — a transition largely attributed to Manusmriti (The Laws of Manu) which propounds patricentric control over women. Lal urges the wisdom that would ensue to “recall Mahatma Gandhi’s words: ‘Man and woman are of equal rank but they are not identical’.”

Makarand R Paranjape’s Radha, Divine Paramour focuses on the “immortal love of ‘lover-God’ Krishna and his consort Radha, ‘a milkmaid elevated to the status of the erotic and holy beloved of the Supreme Godhead.’” He wonders how the dialogue between Radharani and Mahatma Gandhi would progress if they were to meet when he was trying to rid himself of all sexual passions for the sake of society and polity...

Ghalib’s Poetic Beloved: Cruel, Willful, and Elusive by Mehr Afshan Farooqi and Love, Society, Polity: Urdu Poetry from Khusro to Faiz by Zafar Anjum explore the various aspects of love in Urdu poetry, while Rakhshanda Jalil’s essay, Barahmasa: Songs for the Seasons of Love and Separation, explores the tradition of barahmasas, rural and oral songs of separation which emerged as a counterbalance for the classicism of the ghazal. They vocalise the needs of the women, their wishes and desires. The irony is that although they were in zenana boli, they were composed by men.

Alka Pande, in her essay, Love, Longing, and Desire: A Nayika’s Tale, delves into the question: Is Kamasutra simply a sex manual or is it much more than that? Is this encyclopaedia of human emotional behaviour a treatise on the Indian philosophy of the purusharthas — dharma, artha, kama and moksha?

She explores this code of conduct of sexuality — which is rooted in a time “when women were treated as equals and were as entitled as men to sexual pleasure” — from the vision of renowned courtesan Amrapali. The nayika and nagarvadhu of Pataliputra never subjugated herself to any man. “I am Amrapali, who chooses her men with care, finesse and her free will.” Pande concludes that the Kamasutra is to be viewed “not as a sexual-yogic manual but a handbook of living life to its fullest.”

In her personal essay, Swipe Me Left, I’m Dalit, Christina Dhanaraj speaks up about the romantic experiences of dalit women who are dealt the double whammy of the burden of caste and gender. It is based on her experiences that began when she was a budding young feminist coming to terms with her dalit identity. She naively believed that it would never threaten her romantic relationships. The essay transverses from the author’s state of illusion to reality when she realises that caste not only plays “a role in determining the success of one’s romantic pursuit, it can also shape one’s competence, desirability, and confidence within a relationship”. Love, she says, is a matter of privilege, not choice. Even today, the all-important question remains: What is your caste?”

Nilanjan Mukhopadhyay’s Love Jihad examines if inter-faith love and marriages can survive when religion becomes politicised.

If the challenges to heterosexual love are manifold, same-sex love faces many more social-political-legal obstacles. In her essay, Same-sex Love in India, Parvati Sharma positions her essay against the backdrop of the decades-old legal battle around the controversial Section 377 of the Indian Penal Code simultaneous to her own coming to terms with her sexual preference. “Having tried to ‘un-gay’ myself by running away, dating boys and growing my hair, I finally took an about-turn,” she writes.

Love is not a simple emotion. It carries with it centuries of cultural habits, changing philosophies, shifting gender identities, patriarchy, differing politics emerging from religion, race and gender. Probably it is the most complex of emotions and motivations. In her preface, Dhar says: “Why, I wondered, while watching the leaves change colour in the fall, were there very few serious yet engaging books on love, its many moods and multiple meanings?” Well, her compilation certainly tries to fill the gaps.