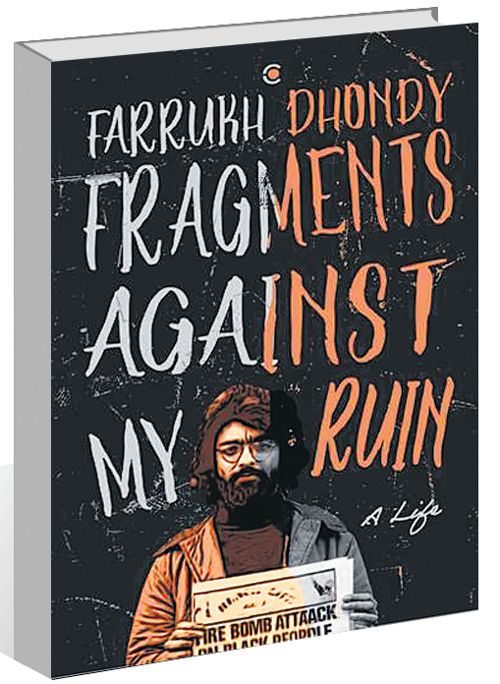

Fragments Against My Ruin — A Life by Farrukh Dhondy. Westland. Pages 306. Rs 699

Book Title: Fragments Against My Ruin — A Life

Author: Farrukh Dhondy

Amitabha Bhattacharya

FARRUKH DHONDY is a familiar name, but his books were not in my priority list. Having read this memoir, I realise how much I had missed out. There are reasons why this book stands out against standard autobiographical fares.

Firstly, the literary quality that informs every page of the work in a language that is precise and witty. Secondly, Dhondy exhibits a rare degree of frankness in revealing himself, as also others, eminent and ordinary, observed through his acute mind. Thirdly, while narrating interesting episodes, acquired from real life, he displays a sense of conviviality that is free from malice. Finally, he focuses primarily on individuals and experiences that have influenced him in evolving as a person of talent and enterprise. Dhondy captures the decisive moments.

Born in a Parsi family in 1944 as a son of an Army officer, he traces his life through Poona, Kanpur, Delhi, Bombay, Cambridge and London and other parts of the world — as a student, writer and journalist, a schoolteacher and activist, a commissioning editor for Channel 4 television network, England (1984-1997), and as a lover of good things. The drama of his life, through unexpected twists and turns, has been unfolded in a manner that is truly absorbing.

He tells us about his various romantic liaisons starting from the college days and names them all. He shares the details of how he and his close friend, in their youthful exuberance, had concocted a story about the past of osteopath Stephen Ward, involved in the sensational Profumo-Keeler scandal of the early Sixties, for a newspaper of Poona. He narrates his early encounters of the adult world, of his years as a natural science student at Cambridge, and of racial prejudice and other abuses. But he understands, learns and moves on, facilitated through his involvement with the British Black Panther movement and such causes as a young Marxist. Gratefully, he also acknowledges how destiny catapulted him to fame.

Dhondy’s intimate associations with literary luminaries like CLR James and Vidia Naipaul are as skillfully portrayed as those with Charles Sobhraj, and Subhash Ghai of Bollywood, for example. He describes with a touch of fun how he was unofficially but substantially involved in the script-writing of films like ‘Bandit Queen’, ‘Immaculate Conception’, ‘Train to Pakistan’ and ‘Jinnah’ as the commissioning editor of Channel 4 network, in a chapter titled ‘Films I Didn’t Write’. He follows it up with another, ‘Films I Did Write’. The unexpected problems and litigations that arose before the release of the film on Phoolan Devi, and how the issue was ‘fixed’ and the case withdrawn have been candidly brought out. He has not shied away from naming the dramatis personae.

The sordid tale that eventually landed Jeffrey Archer in jail, why Richard Attenborough had been upset with Dhondy for his remarks on the film ‘Gandhi’, how Sobhraj wanted to know the meaning of ‘Red Mercury’, his brief encounters with Oprah Winfrey or Allen Ginsberg, attending the Oscar ceremony with Mira Nair, and a plethora of such interesting allusions make every page of the book spring to life.

Naipaul confided that his authorised biography contained crucial factual errors, and James, best known for his autobiographical ‘Beyond a Boundary’, foresaw the enormous potential of television as a mass medium. They meant a great deal to Dhondy. The book is more than about celebrities. It is as much about his friends, relatives and ordinary men and women, many from the small and enchanting world of the Parsis, who touched his life.

Memories of childhood and adolescence have been lovingly recreated, like the fond remembrance of Chandri — a much abused woman, ‘a young Maratha girl whom my grandmother employed a generation ago and who had now dedicated herself, almost like an honorary granny rather than a domestic worker in the house, to looking after my mother’s children...’ Her life has been affectionately recounted in verse.

A delectable read, about an unusually interesting life.