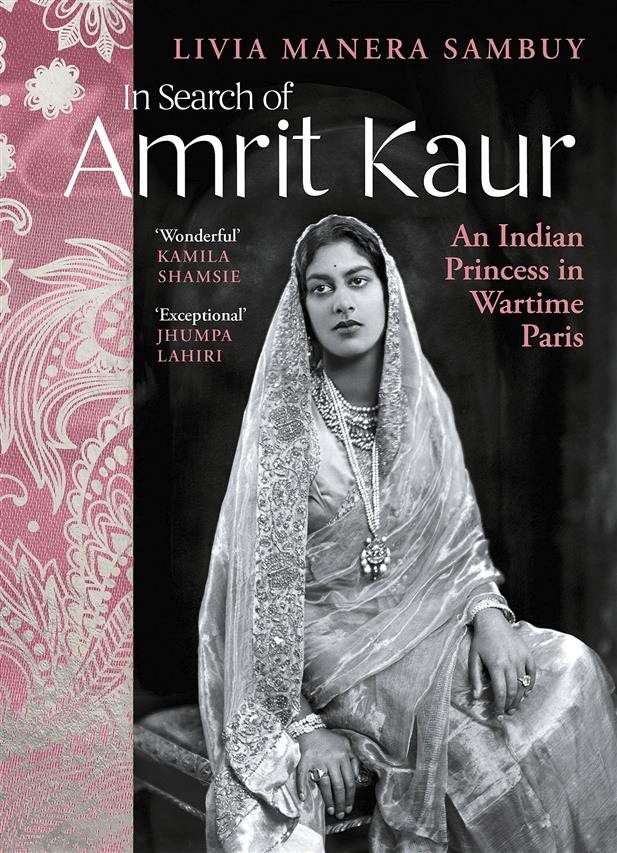

In Search of Amrit Kaur by Livia Manera Sambuy. Translated by Todd Portnowitz. Chatto & Windus. Pages 352. Rs 799

Book Title: In Search of Amrit Kaur

Author: Livia Manera Sambuy

Vikramdeep Johal

Opulence, decadence, intrigue — this heady concoction makes royalty an enduring subject that interests not only scholars and researchers but also the lay reader. ‘In Search of Amrit Kaur’ has all the ingredients of a bitter- sweet royal saga, but there are plenty of twists and turns on the way.

In 2007, Italian writer Livia Manera Sambuy saw a photograph of Amrit Kaur, the lone daughter of former Maharaja of Kapurthala Jagatjit Singh, in a Mumbai museum. The caption claimed that the princess was arrested by the Gestapo in occupied Paris on the charge of selling her jewellery to help Jews flee the country; she was sent to a concentration camp, where she died within a year. Wondering whether this amazing story was true and how it had remained buried for so long, Sambuy set out on an investigative journey during which she encountered quite a few surprises; to top it all, there was a series of eye-opening meetings with Amrit Kaur’s octogenarian daughter Bubbles. And of course, the author went on to discover the truth, which was indeed stranger than fiction.

Rani Amrit Kaur, not to be confused with her namesake and cousin Rajkumari Amrit Kaur (a freedom fighter and Independent India’s first Health Minister), was born in 1904. Her father got her married to Raja Joginder Singh of Mandi when she was 19. The strong-willed Amrit, a champion of women’s rights who resented polygamy, was not the one to humbly settle down into regal domesticity along with other princesses. Better educated and more knowledgeable than her husband, she had no reason to consider herself inferior to him in any way. Feeling suffocated by patriarchal shackles and spurred by her thirst for freedom, she eventually took the plunge and fled to France in 1933, abandoning her little children. Confined to an internment camp by the Nazis, she was released in exchange for another prisoner. Her final years, spent in England, were scarred by financial and health problems. She died unsung in 1948 — a turbulent life ended not with a bang, but a whimper.

This is a fascinating portrait of a woman who lived life on her own terms, for better or worse, and refused to be straitjacketed into the role of a charming and dutiful princess. Along with Amrit Kaur, there are a couple of other feisty women who figure here — legendary Hungarian-Indian painter Amrita Sher-Gil and Spanish flamenco dancer Anita Delgado. The latter, one of the wives of Maharaja Jagatjit Singh, was the protagonist of Javier Moro’s engrossing book ‘Passion India: The Story of the Spanish Princess of Kapurthala’ (2007). She had an unusual relationship with Amrit Kaur, being more of an elder sister than a stepmother.

“Providence created the Maharajahs to offer mankind a spectacle,” Rudyard Kipling thus summed up the appeal of India’s kings and princes. This book offers insightful glimpses into the lives of Punjabi royals in the first half of the 20th century. Rulers of many princely states had no qualms about kowtowing to the British in order to protect their fiefdoms and retain their regal splendour, even as the freedom movement gained momentum in the 1920s. Mahatma Gandhi had a low opinion of this privileged class: “It is no credit to the Princes that they allow themselves powers which no human being, conscious of his dignity, should possess. It is no credit to the people who have mutely suffered the loss of elementary human freedom.”

India’s Independence sounded the death knell for the monarchs and their scions, leaving them grappling with their personal tragedies and inner demons. Within two years after 1947, Amrit Kaur and her father passed away, separated by continents and much else. The end of the Raj — and also the end of a world — preceded the culmination of their life’s journey, and fittingly so. Sambuy deserves praise for bringing the story of a forgotten princess to the forefront. There is also a sense of personal fulfilment for the author, who feels that ‘reconciling Bubbles with her mother had been the key that set me free’.