Languages of Truth: Essays 2003-2020 by Salman Rushdie. Penguin Random House. Pages 350. Rs 799.

Book Title: Languages of Truth: Essays 2003-2020

Author: Salman Rushdie

Rohit Mahajan

IN this anthology of essays written in the first two decades of this century, Salman Rushdie quotes Milan Kundera to explain his own writing method — of wild flights of imagination and conceit and utterly fantastical happenings — in these words: “Kundera was suggesting that the possibilities of the realist novel have been so thoroughly explored by so many authors that very little new remains to be discovered.”

Thus, Rushdie adds, that for innovation, “we must turn to irrealism and find new ways of approaching the truth through lies”, and that the mantra “write what you know” leads to a “lot of stuff about adolescent suburban angst”.

These thoughts explain his embrace of fabulism, which led to fantastical sentences, situations and stories that made him an acclaimed writer — but he did go out of flavour a long time ago. The magic didn’t cease but became a bit too magical; the surprise element of the 1980s was gone and the irrealism became banal through surfeit. Rushdie invokes the ‘Panchatantra’ — the talking jackals and the feuding crows and owls — and the ‘Arabian Nights’ and ‘Aesop’s Fables’ to build up a case that the yearning for the fabulist story is universal; he delights in tracing the journey of such tales from India “all the way down to the magic realism of the South American fabulists”.

Rushdie believes realism has beaten magic realism, sadly, and seems to mourn this. This opening essay is his act of defiance against unkind reviewers and unloved books.

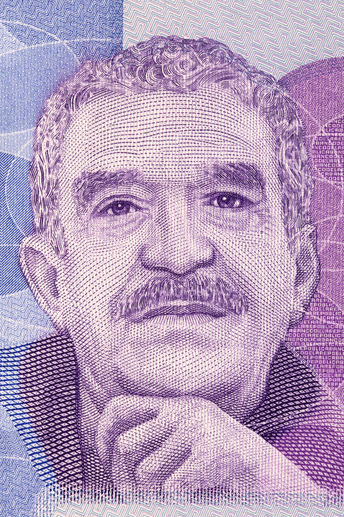

Rushdie first read Gabriel Garcia Marquez’s ‘One Hundred Years of Solitude’ in 1975; expecting “insufferable tedium”, he “fell deeply in love”. However, he notes that in “Latin America and beyond, the grand moment of magic realism has passed”; he regrets that the writer Roberto Bolano “notoriously declared that magic realism ‘stinks’ and jeered at Marquez’s fame, calling him ‘a man terribly pleased to have hobnobbed with so many presidents and archbishops’”. Interestingly, Rushdie has faced similar criticism for his ‘Joseph Anton’, in which he seemed a bit too excited, for a great writer, on meeting famous people such as Madonna.

In the 1980s, when Rushdie was a novelist deeply invested in the political, he wrote: “What I am saying is that politics and literature, like sport and politics, do mix, are inextricably mixed, and that that mixture has consequences.”

There were consequences in his particular case. He had to apologise to Indira Gandhi and remove a paragraph from ‘Midnight’s Children’ after she sued him; in a far more frightful situation, the supreme leader of Iran, Ayatollah Khomeini, gave a fatwa calling for Rushdie’s death after the publication of ‘Satanic Verses’. An atheist who questioned religion since early youth, a Left-leaning young man who supported Iran’s Islamic Revolution against the Shah in the early stages, Rushdie was soon christened an “Islamophobe”.

“Let’s be clear,” writes Rushdie in ‘The Liberty Instinct’, “The gods did not create us in their image. We created them in ours.”

Rushdie asserts that the religious explanation regarding the origins of human beings is “100 per cent wrong” — that “science has better stories and many of them are verifiable”.

In surely the most belated exculpation in the world’s history, it was only in 1964 that Jews were finally relieved of the collective guilt of deicide — god-killing — by the Roman Catholic Church. It took some 1,931 years. In 1633, Galileo was placed under a lifetime of house arrest for believing that the earth moves around the sun. It took the Catholic Church 359 years to acknowledge that the great Galileo was right, after all.

After a bloody Reformation, lasting centuries, Christianity was defanged. Blasphemy was normalised — offence-taking is not an option in European Christianity, and the ideal of free speech promoted. Other religions must realise, urgently, that all ideas, including religious ideas, must be open to examination — and even mockery.

In perhaps the most fond essay in this collection, written on the day Christopher Hitchens died, Rushdie pays tribute to his friend — who “went to war” for Rushdie after even the Pope “failed to be outraged” by Khomeini’s death fatwa.

From Shakespeare to Cervantes, Akbar to Vonnegut to Bin Laden, Rushdie paints on a vast canvas in this book; he deals in platitudes, too, as in addresses to students or memorial speeches, repurposed as essays here.

It’s in his literary observations, such as on Amrita Sher-Gil’s letters, that he shines the brightest.