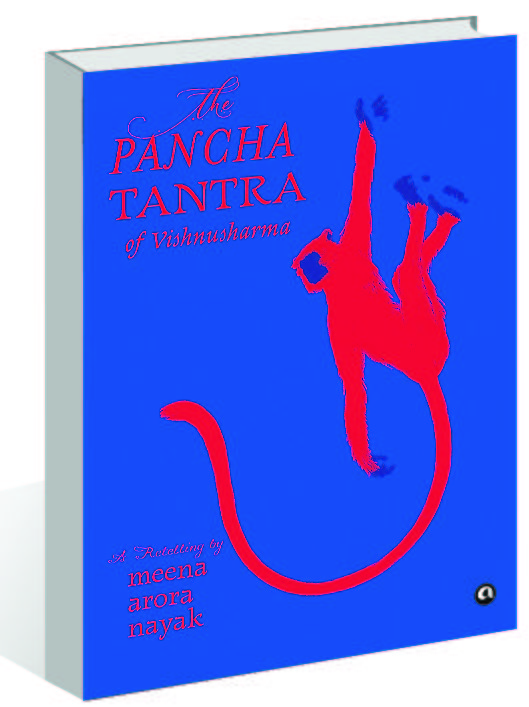

The Panchatantra of Vishnusharma: A Retelling by Meena Arora Nayak. Aleph. Pages 373. Rs 999

Book Title: The Panchatantra of Vishnusharma: A Retelling

Author: Meena Arora Nayak

Aradhika Sharma

Vishnusharma’s ‘Panchatantra’, authored in about 345-300 BCE, is a treasure trove of lessons in statesmanship, kingship, strategy, governance, polity, conduct and the duties of a ruler. This collection of fables is a corpus of stories. Although in the present day, it is largely simplified as children’s literature, ‘Panchatantra’ has sustained its impact on world literature. In this retelling, Meena Arora Nayak brings 69 stories from ‘Panchatantra’ to a new generation of readers.

It is said that ‘Panchatantra’ was created as a set of stories to educate the three unschooled sons of King Amarashakti of Mahilaropya. The wise king, despairing of his sons’ nescience, sought out the octogenarian scholar Vishnusharma to educate the young men on being good rulers. The venerable sage accepted the task, promising to accomplish it in six months. To equip his students with the maxims of political ethics and principles of good government, he composed the ‘Panchatantra’ or the five treatises.

The great work abounds with animal, bird, and aquatic protagonists — lions, tigers, wolves, cats, tortoises, monkeys, deer, hares, snakes, crows, fish and crabs. However, explaining that ‘Panchatantra’ is an allegory of humanness, Nayak explains that the “animals are not zoomorphic; they are actually humans wearing the mask of animals”.

‘Panchatantra’ uses the frame narrative or a ‘story within a story’ technique in which the narrator in one setting tells a story set in another time and place and is divided into five sections. The theme running through the first two sections is friendship and political and social alliance. The first tantra, consisting of 30 fables, is titled ‘Mitra Bheda’ (Estrangement or dissension among friends), while the second tantra, consisting of 10 fables, is titled ‘Mitra Samprapti’ (Winning of friends and allies). The third, consisting of 18 fables, titled ‘Kakolukiyam’ (The story of crows and owls) is about war and peace. The fourth section, consisting of 13 fables, is called ‘Labdha Pranasham’ (Loss of acquired gains) and the fifth, consisting of 12 fables, is titled ‘Aparikshita Karakam’ (Ill-considered actions).

Each part contains a frame story with several embedded stories narrated by one character to another.

There are innumerable pithy verses interspersed in the stories, often in the form of a dialogue between characters. Usually replete with universal truths, they provide practical directions to life.

‘A friend during adversity

Is a true friend indeed

In times of prosperity

Even the evil and the wicked

Call themselves your friend’

—

‘Unless one puts in the effort

and does not shy from taking risks,

success and progress do not happen.

Even Suryadeva must climb the scales of Libra

to win victory over rain clouds.’

—

‘Anger is a useless emotion for a man

Who cannot do anything about it

No matter how high a chickpea bounces

It cannot crack open the roasting pan’

Many stories are familiar to Indian children — the blue jackal, the turtle and the geese, the monkey and the crocodile, the tale of the iron-eating mice and the boy devouring falcon, the story of the woman who killed her mongoose son, the hare that outwitted the lion, the tale of the mice that freed the elephant, the tale of the jackal who thought he was a lion. Of the 84 stories in the ‘Panchatantra’, Nayak has chosen 69 for her anthology, bringing them to the contemporary, adult gaze. She has retained the timelessness of this splendid literature, while making it a modern and absorbing read.

In the introductory essay, Nayak, a professor of English and mythology, discusses the genesis of ‘Panchatantra’ and its popularity across the world, where it manifested in different versions. She speaks at length about the five tantras, cites scholars’ views and references the earliest literatures around the world containing tales depicting anthropomorphic animals.